On 29 February 2024, Dr Nick Kapur from Rutgers delivered an important and fascinating talk at the Institute for Historical Studies. The talk was entitled “Participatory Crisis Archiving: The Japan Disasters Digital Archive”.

The origins of The Japan Disasters Digital Archive lie in the catastrophic events of March 2011. On the afternoon of 11 March 2011, a 9.0 earthquake struck the Pacific floor just eighty miles to the east of Sendai, Japan. This earthquake caused a tsunami that raced towards the Japanese shore at 500 miles per hour, generating waves as high as 12 feet in Hawaii. In Japan, a 33-foot wave crashed into coastal cities, damaging everything in its path and flooding up to six miles inland. These disasters caused massive death and devastation, killing almost 20,000 people. The devastation was worst on the east coast of Honshu, the main island of Japan.[1]

In a country heavily dependent on nuclear power, a powerful earthquake and tsunami can mean even greater disaster. As a result of the strong tremors and massive tsunami, the nuclear power plant at Fukushima Daiichi experienced partial meltdowns and released large amounts of radiation into the surrounding environments. People already impacted by the previous environmental phenomena were forced out of their homes due to radioactivity.[2]

Each of these three disasters by themselves would have resulted in chaos and confusion. The fact that they occurred almost simultaneously, meant that most normal recovery procedures were ineffective. With the large amount of people displaced by the damage to their homes and towns, or forced out because of the Fukushima Daiichi meltdown, citizens turned to both the government and social media for information. Twitter (now X) took off as a quick way to find and connect with family and friends in devastated areas, both for those in Japan and outside of it. Additionally, government websites gave continually-updated information on search and rescue efforts and the radiation levels in Fukushima prefecture. Such digital tools presented the best and fastest way to communicate and share information in the aftermath of March 11th.

The amount of information and data created immediately after these events, and in the years afterwards, was enormous. Hundreds of thousands of citizens searched for family and friends. Equally large numbers took photos and videos of the events and their aftermath. News stations ran twenty-four-hour coverage, and the government was continually updating its websites.

As one group of researchers at Harvard’s Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies sat and watched these events unfold across the globe, they felt the need to do something. This led to the idea of archiving the events in real time. It was a significant departure from past practices. When we think of an archive, we often think of a building that houses old papers, photographs, or books that were made centuries ago. What Dr. Nick Kapur, then a post-doctoral fellow in the department, and the wider team came up with was a brand-new way to archive digital data as it was created.

Today, such an archive is no longer an exception. Other disaster, or “crisis” archives exist, such as the archive for the Covid-19 pandemic (https://archive-it.org/collections/4887) and the Ukraine War (https://ukrainewararchive.org/eng/). The Society of American Archivists even has a Tragedy Response Initiate Task Force and offers a “resource kit” for “Documenting in Times of Crisis.”[3] These archives use documents that are “born-digital,” or that were digitally created and so do not have to be digitized to be added to the archives. However, at the time, Kapur and his colleagues were at the forefront of this style of archive and one of the first groups to attempt such a documentation project.

With the support of the Reischauer Institute at Harvard and the involvement of influential Japan historian Andrew Gordon, Dr Kapur and the wider team came up with The Japan Disasters Digital Archive. Kapur became the manager of the project. They immediately began crucial discussions over how to document an event that was still unfolding. One key question was the goals of the archive itself. They first asked, “who is this archive for?” Their answer shaped how they developed their goals of research, teaching, and commemoration. They wanted to index, preserve, and make widely accessible digital records of the triple disasters in Japan in March 2011 for research. They also wanted to design an integrated platform that would be useful to students and teachers alike in learning and teaching about the 3/11 disasters, historical documents, digital methods, and crisis archiving.Finally, they wanted the archive to serve as a space of shared memory for those most affected by the disasters and most concerned about their consequences, allowing them to create their own narratives with the sources.

Based on these goals, the wider team developed some guiding principles that informed how they created and worked within their newly created archive. They wanted it to be open access and open source. It was to be digital and distributed, so that there would be redundancy and a “safety-net” for the archive to last into the future. They also wanted it to be participatory and embrace multiple narratives, understanding that victims experienced the disasters in different ways, and thus, there shouldn’t be a single way of narrating the events.

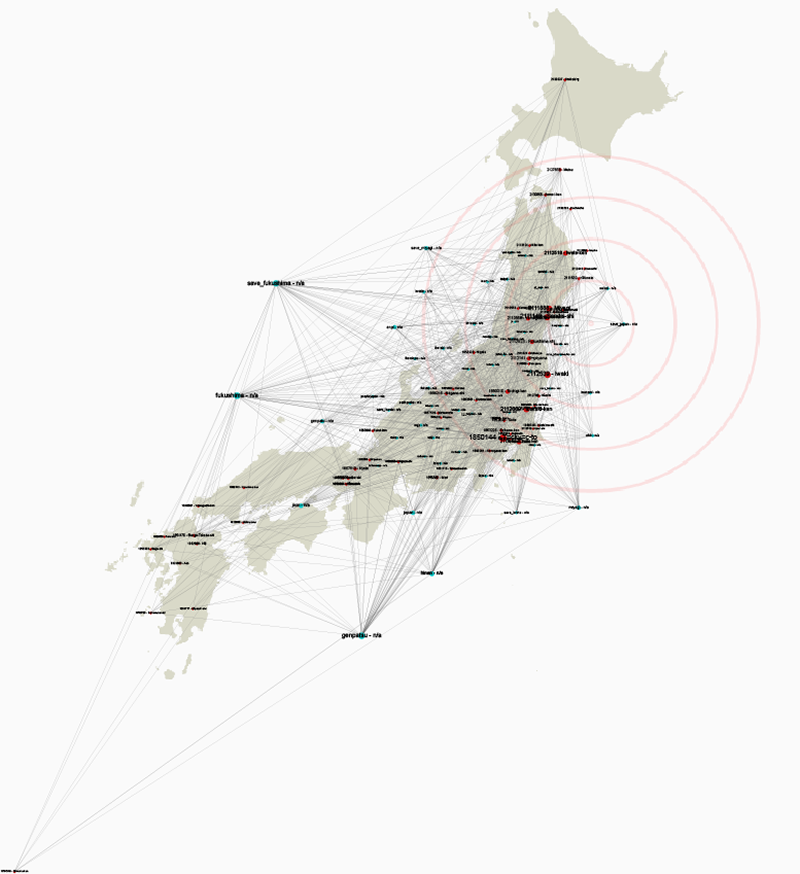

Digital-born archives come with significant advantages. The fact that most of the documents were digital made adding them and other types of sources to the Japan Disasters archive easier, as there was no scanning process. It was also a much faster way to add sources to the archive, so that the team was able to incorporate documents that might have otherwise disappeared, such as tweets or continually updating websites. Digital data also meant that the information was quickly able to work with data visualization applications and metadata analysis functions. Unlike physical archives, digital archives like The Japan Disasters allow for easier reorganization if new systems emerge or ways of cataloging change.

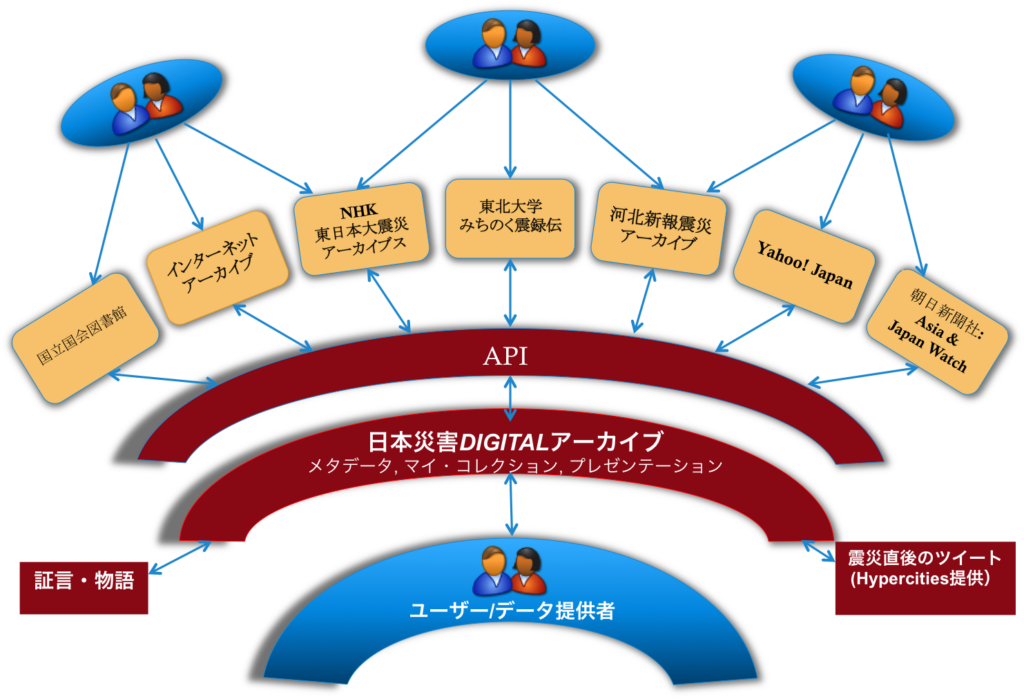

Source: Japan Disasters Digital Archive

One of the biggest advantages to a project like this lies in the ready participation of the public. Digital archives close gaps between archivists, archive users, and event participants and victims. They allow for a back-and-forth engagement between producers and consumers of knowledge. The public can add sources and explore the archive in ways that allow them to develop their own stories and understanding of what happened, instead of having a single narrative imposed by archivists or historians. The website allows for each visitor to create their own “collection” of sources from the archive, in effect creating their own curated exhibit based on their own interests or questions. It also allows users to upload their own testimonials, photos, and videos, which adds to the numerous perspectives available within the archive already.

However, with such advantages comes challenges. A significant challenge was the overwhelming amount of data produced during the events. How do you make sure you don’t miss anything? How do you gather it quickly while even more information is being produced, especially the more ephemeral sources that get overwritten or disappear faster than the rest? One solution was adopting an open-source approach, which allows users to contribute sources that are not already in the archive. Also, much like traditional archives, digital archives also face storage issues. While more traditional archives need the physical space for books, boxes, and files, digital archives need space either in the “cloud” or on physical servers. Both digital spaces not only cost money, but also bring up questions of the durability and accessibility over time: floppy disks were seen as an indispensable storage technology until the CD and now cloud storage (good luck finding a computer today that can read a floppy disk). How can digital archives and archivists make sure that the sources are accessible over the long run? The same issues arise when talking about the software used for interfacing with the sources – will the software used today still work in ten, twenty, or thirty years?

The Japan Disasters archive is not alone in facing these questions. Every digital library, archive, and platform faces the questions of future technological changes. While there is no single solution, Kapur hopes that the foundations put in place will help to steer the archive in the right direction down the line.

One final problem that was unique to Japan was the issue of copyright and image rights. Japan has restrictive copyright laws, and their image rights require the personal approval of every individual shown in an image or video – something that could be impossible during times of crisis and chaos. While the United States has far less restrictive laws on some of these topics, especially image rights, The Japan Disasters archive is committed to respecting the wishes of its Japanese partner institutions and, by extension, Japanese citizens. Their commitment seems to have paid off. Over the thirteen years, the archive has served as a lesson in successful partnerships, as no content partners, such as major Japanese media channels, have left the archive and almost all the data is still available.

Today, The Japan Disasters Digital Archive includes over 735 collections curated from over 1.5 million items in both English and Japanese. While Dr. Kapur no longer actively manages the archival team, he is still active on the site. The amount of data the archive collected, and continues to collect, will be invaluable for future researchers and historians when they look back on the three overlapping disasters of 3/11.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

[1] Kenneth Pletcher and John P. Rafferty, “Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011,” Britannica, viewed 4 March 2024: https://www.britannica.com/event/Japan-earthquake-and-tsunami-of-2011.

[2] Pletcher and Rafferty, “Japan earthquake and tsunami of 2011.”

[3] See https://www2.archivists.org/groups/tragedy-response-initiative-task-force for information on the Task Force and https://www2.archivists.org/advocacy/documenting-in-times-of-crisis-a-resource-kit for the Resource Kit.