Set during the nascent years of the Indian nationalist movement in the fictitious North Indian town of Chandrapore, E.M. Foster’s novel, A Passage to India, follows Adela Quested, a young English woman visiting India for the first time. During a trip to the nearby Marabar caves, Adela accuses Dr. Aziz, an educated and well-reputed Muslim, of attempting to rape her. The contentious trial, which follows Adela’s accusation, brings to the surface the racial and sexual tensions of the British Raj.

British officials condemn Dr. Aziz before the hearing begins, and the judge comments at the onset of the trial that “the darker races are physically attracted to the fairer races but not vice versa.” Foster implies, but never explicitly states, that Dr. Aziz never molested Adela and that she imagined the entire incident. Therefore, the British abuse of power, or more explicitly British colonialism, and not the attempted rape, represent the real crime in the novel. Forster unashamedly condemns British colonialism, which he believes victimizes not only Indians, but also British women. Even though Adela causes Dr. Aziz great distress, Foster portrays her as a victim of patriarchy. As the literary critic Jenny Sharpe explains, colonial officials, “treat Adela as a mere cipher for a battle between men.”

British officials condemn Dr. Aziz before the hearing begins, and the judge comments at the onset of the trial that “the darker races are physically attracted to the fairer races but not vice versa.” Foster implies, but never explicitly states, that Dr. Aziz never molested Adela and that she imagined the entire incident. Therefore, the British abuse of power, or more explicitly British colonialism, and not the attempted rape, represent the real crime in the novel. Forster unashamedly condemns British colonialism, which he believes victimizes not only Indians, but also British women. Even though Adela causes Dr. Aziz great distress, Foster portrays her as a victim of patriarchy. As the literary critic Jenny Sharpe explains, colonial officials, “treat Adela as a mere cipher for a battle between men.”

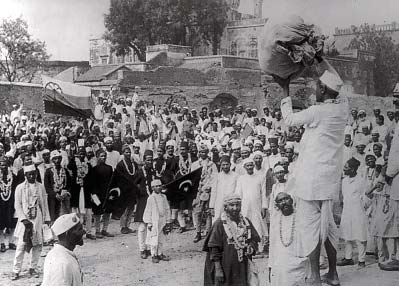

Furthermore, Foster’s perceptive eye captures the political forces at work. Published in 1924, A Passage to India anticipates the nationalist movement’s eruption and India’s and Britain’s final rupture. “India should be a Nation!” yells Dr. Aziz in a spurt of passion. “India a Nation? What an apotheosis!” replies Mr. Fielding. At the end of the novel, Dr. Aziz and Mr. Fielding accept their differences and reconcile, but the two shall never be close friends again. “Why can’t we be friends now?” says Mr. Fielding to Dr. Aziz. “It is what I want. It is what you want,” replies Dr. Aziz. But the friends “swerved apart” because “the earth did not want it,” because “the sky said ‘No.”

Yet, to focus only on the political implications of the novel, and not mention its artistic accomplishments, would do a great disservice to Foster’s genius. He tells the story as an outsider and describes an India that is foreign, exotic, and incomprehensible to him – an India, that he lusts to understand, but humbly acknowledges he could never master. Forster recognizes his shortcomings as an outsider and perhaps that is why instead of attempting to present a whole and coherent picture of India, he sets out to capture special details: a festival, the monsoon sun, a man’s love of poetry. In his characteristic colorful style, Foster writes: “As it rose from the earth on the shoulders of its bearers, the friendly sun of the monsoons shone forth and flooded the world with color,” Simple, yet evocative passages such as this one, lend a magic touch to this extraordinary story and bear responsibility for the novel’s enduring popularity.

Yet, to focus only on the political implications of the novel, and not mention its artistic accomplishments, would do a great disservice to Foster’s genius. He tells the story as an outsider and describes an India that is foreign, exotic, and incomprehensible to him – an India, that he lusts to understand, but humbly acknowledges he could never master. Forster recognizes his shortcomings as an outsider and perhaps that is why instead of attempting to present a whole and coherent picture of India, he sets out to capture special details: a festival, the monsoon sun, a man’s love of poetry. In his characteristic colorful style, Foster writes: “As it rose from the earth on the shoulders of its bearers, the friendly sun of the monsoons shone forth and flooded the world with color,” Simple, yet evocative passages such as this one, lend a magic touch to this extraordinary story and bear responsibility for the novel’s enduring popularity.

You may also like:

Voices of India’s Partition – Part 1

Sundar Vadlamudi’s review of Great Soul: Mahatma Gandi and his Struggle with India

Amber Abbas’s reviews of Krishna Kumar’s Prejudice and Pride: School Histories of the Freedom Struggle in India and Pakistan and Urvashi Butalia’s The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India

UT professor of history Gail Minault’s review of The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan and Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children

Photo credits:

Photographer unknown, Hindus and Muslims displaying the flags of both the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League as a part of Mohandas Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation Movement in 1922

via Wikipedia