by Gail Minault

We are in the delivery room in Bombay, at midnight on August 14/15, 1947, the moment India and Pakistan are created as independent nations. Two children enter the world simultaneously, one Muslim, one Hindu, and their destinies will be determined by the timing of their birth. Through their eyes, and especially through the eyes of Saleem Sinai, the reader travels around the subcontinent, meeting the other children of partition and viewing every major national event until Saleem Sinai quite literally disintegrates. Saleem is the reader’s guide through the world of independent India and Pakistan; its problems become his problems in fantastic and unpredictable ways. Through this journey, Saleem must face his past and his future, and it is not always clear how they will come together.

Two children enter the world simultaneously, one Muslim, one Hindu, and their destinies will be determined by the timing of their birth. Through their eyes, and especially through the eyes of Saleem Sinai, the reader travels around the subcontinent, meeting the other children of partition and viewing every major national event until Saleem Sinai quite literally disintegrates. Saleem is the reader’s guide through the world of independent India and Pakistan; its problems become his problems in fantastic and unpredictable ways. Through this journey, Saleem must face his past and his future, and it is not always clear how they will come together.

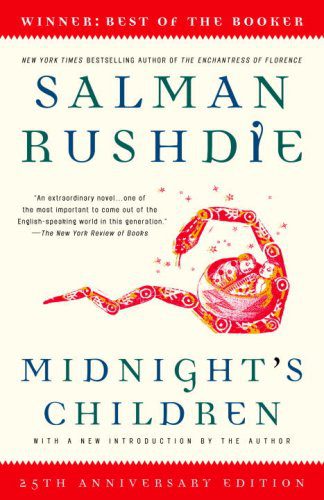

Midnight’s Children, winner of the 1981 Man Booker Prize, stands out as the most compelling account of the surreal aspects of partition experienced by families throughout the affected areas. While it may seem unusual to turn to a work of magic realism for guidance on a topic as complex as partition, Rushdie captures the tensions of these historical events better than most standard histories. There are no Viceroys or national fathers in Rushdie’s novel. But there are fathers and mothers, lovers, sons and daughters, friends and bitter enemies. As a young Muslim entering newly created Pakistan, Saleem loses his memory, loses his connection to his past, his connection to the history of Muslims in India; now relegated to a separate chapter, a separate country, a separate history.

The realities of partition, it seems, are best interpreted through Rushdie’s magical landscapes. Writing in English, he nonetheless expands a body of Urdu and Hindi literature that, in the months and years after the traumatic migrations of 1947, tried to capture the sense of unease that the divide introduced. These stories and poems looked into the dark heart of partition, long before the high politics had concluded or become fodder for official histories. As in Saadat Hasan Manto’s famous Urdu short story of partition, Toba Tek Singh, where the actions of the sane appear insane, and the insane sane, Rushdie builds upon a tradition of interpretation that goes beyond the histories of real actors and dives into partition’s fictions, its profound surreality.

Further reading:

Hosain, Attia. Sunlight on a Broken Column. New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1992.

Ravikant, and Tarun K. Saint, eds. Translating Partition: Stories by Attia Hosain, Bhisham Sahni, Joginder Paul, Kamleshwar, Sa’adat Hasan Manto, Surendra Prakas. New Delhi: Katha, 2001.

Singh, Khushwant. Train to Pakistan. New Delhi: Roli Books, 2006.

Zaman, Niaz, ed. The Escape and Other Stories of 1947. Dhaka: University Press, 2000.