By Mark Sheaves

In 1554 Mary Tudor Queen of England married Prince Phillip II of Spain, uniting the two crowns for four fascinating years until Mary’s death in 1558. In Philip of Spain, King of England, Harry Kelsey explores the rise and fall of this dynastic alliance in the context of the Reformation era. By highlighting this union, he demonstrates that sixteenth-century Anglo-Spanish relations were not simply dominated by religious difference, piracy, and imperial rivalry. For a brief period at least the histories of England and Spain were not only deeply entangled, but wedded together.

In 1554 Mary Tudor Queen of England married Prince Phillip II of Spain, uniting the two crowns for four fascinating years until Mary’s death in 1558. In Philip of Spain, King of England, Harry Kelsey explores the rise and fall of this dynastic alliance in the context of the Reformation era. By highlighting this union, he demonstrates that sixteenth-century Anglo-Spanish relations were not simply dominated by religious difference, piracy, and imperial rivalry. For a brief period at least the histories of England and Spain were not only deeply entangled, but wedded together.

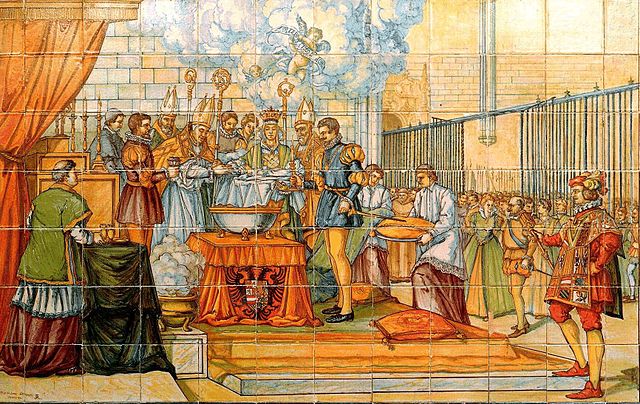

Structured as a dual biography of Mary and Philip, Kelsey focuses on the importance of the childhood experiences of his two protagonists for shaping their actions as monarchs, both as individuals and a married couple. He emphasizes their very different relationships with their famous fathers. Groomed as an heir to the throne, Philip enjoyed a stable youth and learned the necessary tools to manage the world empire he would inherit from his father, Charles V. Touring the imperial kingdom instilled an ambitious streak in the young prince. Throughout the time he ruled the provincial kingdom of England, Philip remained focused on bigger prizes on the continent. He never learned English and envisioned England’s future as part of a united kingdom with the Netherlands to counter the threat of France in northern Europe. In contrast, Mary’s father, Henry VIII, banished her from court at a young age after he annulled his marriage to her mother, Catherine of Aragon; another Anglo-Spanish royal marriage. This left Mary ill prepared for rule, isolated from European matters, and resolutely Catholic. The goal of returning Catholicism to England dominated her reign, and motivated her decision to marry Phillip. These formative experiences, Kelsey argues, shaped the policies employed during their marriage.

‘The Baptism of Phillip II’ in Valladolid, Spain. Historical ceiling preserved in Palacio de Pimentel (Valladolid). Via Wikipedia.

This clearly written book provides a window onto the complexities of European dynastic politics that led to the brief union between England and Spain, and the barriers that prevented its success. Philip and Mary received marriage proposals from various kingdoms and decisions depended on political gains. During the marriage, the English parliament’s unwillingness to agree to a coronation ceremony ultimately restricted Philip’s ability to govern England and he was never officially confirmed as King. Lacking an heir and preoccupied with defeating France, Philip spent most of the period 1556-1557 abroad. Following Mary’s death and the accession of the firmly Protestant Elizabeth I, this short alliance between the two crowns ended.

While there were limits to Philip’s power in England, Kelsey’s study demonstrates he did play an important role in shaping developments in England during his reign. He helped Mary to stabilize the country and re-establish relations with the Pope. The author emphasizes that through the Privy Council, King Philip of England showed a willingness to engage with English politics and left a lasting impression.

The weakness of the book lies in the lack of depth afforded to other important individuals, the populations of both England and Spain, and important themes from this period. Henry VIII, for example, appears as an irrational sex-addict simply making “rash moves.” Philip’s religious zeal and his central role in promoting increased persecution of Protestants receive barely a line. Kelsey does not offer insight into the reactions of the crowds of people who greeted the new royal couple during their marriage tour of the English towns. It would have been wonderful to include some information on the reception of the marriage by a wider range of individuals, although this may have distracted from the biographical focus on the two main protagonists.

Despite the simplistic characterizations, the book successfully demonstrates how Hapsburg realpolitik led to the brief union between England and Spain, the political factors that hindered a successful alliance between these kingdoms, and the lasting impression that the marriage left on the development of the two countries. Kelsey’s previous publications on sixteenth-century English and Spanish history makes him the perfect navigator for this complex political history.

Harry Kelsey, Philip of Spain, King of England: The Forgotten Sovereign (I.B. Tauris, 2012)

You may also like:

Mark Sheaves recommends Harry Kelsey’s Sir John Hawkins: Queen Elizabeth’s Slave Trader (2003)

Ernesto Mercado Montero discusses Ordinary Lives in the Early Caribbean: Religion, Colonial Competition, and the Politics of Profit, by Kristen Block (2012)

Mark Sheaves reviews Francisco de Miranda: A Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution 1750-1816, by Karen Racine (2002)

Bradley Dixon, Facing North From Inca Country: Entanglement, Hybridity, and Rewriting Atlantic History

Ben Breen recommends Explorations in Connected History: from the Tagus to the Ganges (Oxford University Press, 2004), by Sanjay Subrahmanyam

Christopher Heaney reviews Poetics of Piracy: Emulating Spain in English Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) by Barbara Fuchs

Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006) on Not Even Past.

Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott