From the editors: Not Even Past is honored to publish this tribute to Dr. Karl Butzer in connection with The Climate in Context: Historical Precedents and the Unprecedented conference which will take place on April 22-23, 2021. Dr. Butzer was a long-time faculty member in the Department of Geography and the Environment at UT Austin, which is a sponsor of the conference. He was also one of the first scholars to call attention to the threat of global warming more than 40 years ago. The Department of Geography and the Environment’s support of the conference is in his honor. This profile was adapted by Raymond Hyser from Dr. William E. Doolittle‘s 1999 Robert McC. Netting Award paper and Dr. William E. Doolittle’s PNAS Retrospective “Karl W. Butzer: Interdisciplinary Mentor.”

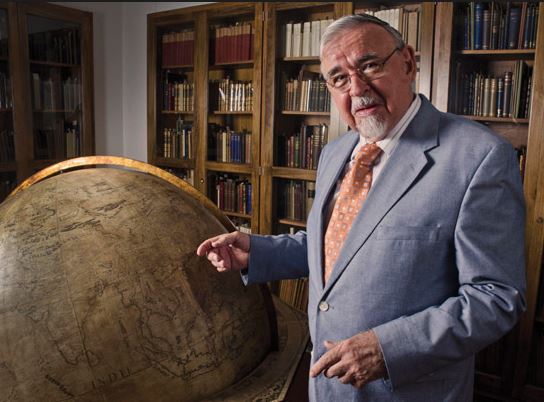

Karl W. Butzer exploded onto the scholarly scene with the publication of his first book, Environment and Archeology: An Introduction to Pleistocene Geography. Described by anthropologist Robert F. Heizer as a “classic” almost immediately after its publication, this book called upon archaeologists to go beyond just data gathering and engage in ecological synthesis. Butzer boldly hoped “for more archeologists who can think as geographers.” Publishing a classic only seven years after receiving one’s doctorate is an accomplishment of the highest order. But then, receiving a doctorate before one’s 23rd birthday is equally impressive, as is publishing no fewer than two monographs and 32 journal articles in the interim. Indeed, Butzer accomplished more during the first seven years of his career than most scholars accomplish in a lifetime. He, of course, did not stop there. He went on to author or edit another 10 books and 230 articles or chapters throughout his academic career.

Although his initial work was in physical geography, in particular climatology and geomorphology, Butzer never thought of landscapes and environments without appreciating the human vector. Similarly, as his work became more “human” in its focus, he never forgot about the importance of physical factors. No one has bridged the natural and social sciences better than he. And, his bridging between the two was not merely being well-read in both, but also being an accomplished researcher in both, separately and in concert with one another. Spanning both the natural and social sciences, Dr. Butzer was a pioneering figure in the field of geoarchaeology where he challenged archaeological and paleo-environmental researchers to critically engage with the complexity of human-environment interactions. Through his research, Dr. Butzer championed human adaptation to environmental change. Before it became “fashionable,” he published a number of articles, like his 1980 article “Adaptation to Global Environmental Change” in Professional Geographer, that called attention to global warming.

You could learn more in one day in the field with Karl Butzer than you could in a semester-long course with any other professor

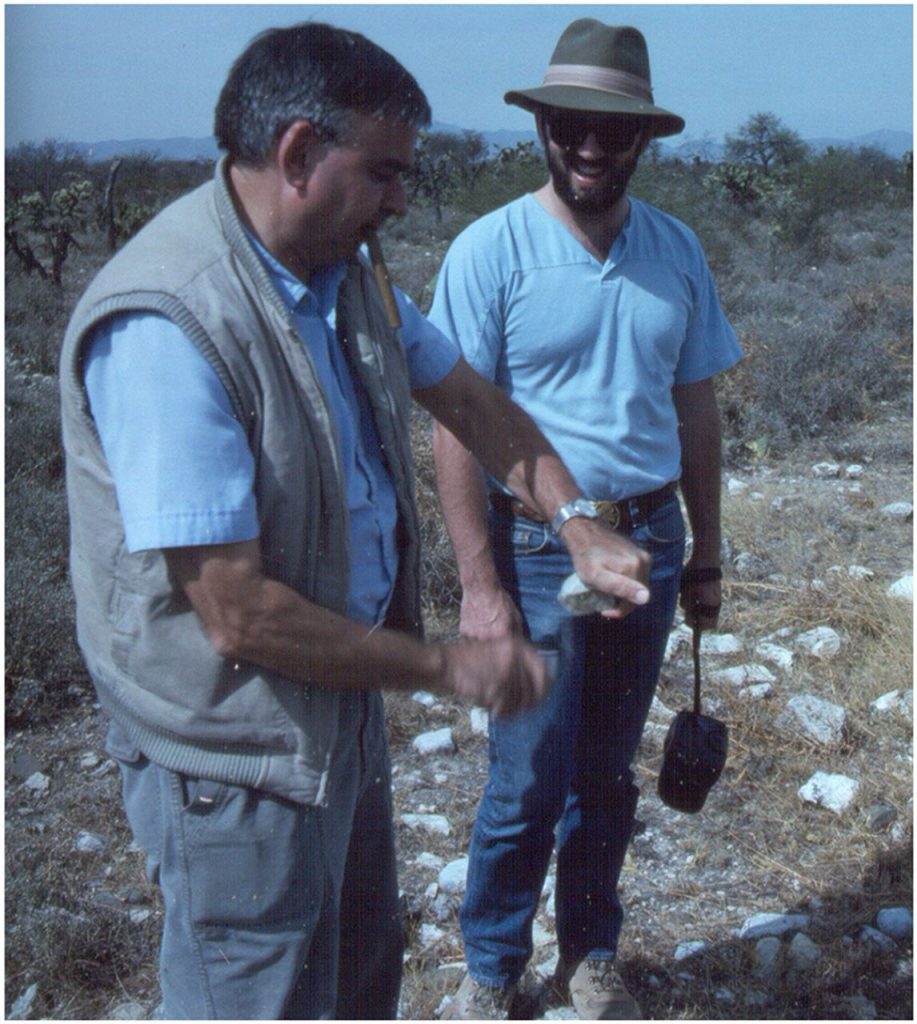

If there is a hallmark to Dr. Butzer’s scholarship, other than it being of exceptional quality and quantity, it is his fieldwork. As a fieldworker, he had no equals. Indeed, everything he had ever published has been based on extensive and intensive first-hand field experiences. South Africa, Chad, Kenya, Ethiopia, Egypt, Mallorca, the Iberian peninsula, Mexico, the United States, Turkey, and Australia have all been the subject of his endeavors. His experiences in these places permeate his writings. Data is always described in meticulous detail and analyzed with the greatest of scrutiny. But Butzer also says as much “between the lines” as he does with the explicit words on the page. One senses in his writings an emotional attachment to people and places as well as to the research itself. Undoubtedly, Butzer’s fluency in multiple languages — German, French, Spanish, and English — accounts for his masterful ability to choose just the right words and phrases to not only describe things but to bring them to life.

Rather than flaunting his knowledge and skills, he employed his expertise as a springboard for discussion, to elucidate observations and interpretations from his traveling companions. Butzer claimed that he learned as much from others as others learn from him. Be they in the field or in the classroom, students loved Dr. Butzer. As a teacher, he knew more about the earth, people, and the relationship between the two than anyone; and much of this came out in his classroom. When Dr. Butzer spoke, students listened intently. Conversely, when students spoke, he reciprocated with undivided attention. Butzer constantly received some of the highest teaching evaluations in UT’s Department of Geography. In addition to being an outstanding teacher in both the field and in the classroom, he was simply great at being a dissertation advisor. Indeed, as good as he is in the other settings, he may well be best at dealing with graduate students one-on-one.

He was born in Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany in 1934. Soon thereafter, his father, a Catholic dissident against Nazism, uprooted the family and fled to London. When World War II broke out the family was interred and, in 1941, sent to Canada where Butzer eventually became a naturalized citizen. He held a special place in his heart for the country that offered his family a home. Despite his reputation as a world-class scholar, a standing that typically carries with it the stigma of being a less than sensitive person, Butzer is a real people person. This very humane and compassionate side of Butzer is one that few members of the academic community knew existed. Perhaps there is a lesson here for parents and school teachers: good geographers are made young and through some sources not normally associated with geographic pedagogy. Many geographers like to think of themselves as multidisciplinary scholars even though members of other disciplines might not accept them. Karl’s case is just the opposite. He has always thought of himself as a geographer, and nothing else, while anthropologists and geologists claim him as one of them. Karl W. Butzer embodies the interdisciplinary spirit of cultural geography like no other scholar.

Sources and photo credits:

Wikipedia: Karl Butzer; Karl W. Butzer: Interdisciplinary Mentor, PNAS; Farewell to Dr. Karl Butzer, University of Texas at Austin Department of Geography & the Environment

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.