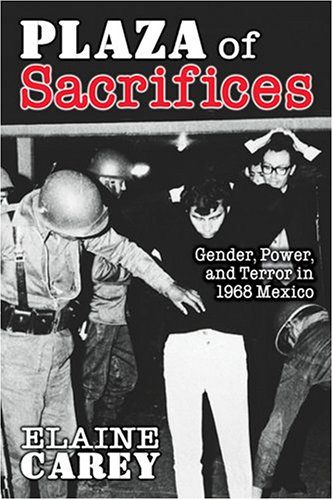

On October 2, 1968, the Mexican government sanctioned the killings of an estimated three hundred student protesters in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas, the main square in Mexico City’s Tlatelolco neighborhood. Hundreds more were arrested, many subjected to torture. Plaza of Sacrifices is the first English-language monograph of the events leading up to and following this massacre. Carey, Associate Professor of History at St. John’s University, offers a gendered analysis of the Mexican student movement of 1968. While Carey focuses on Mexican issues and events, she places the movement into the larger context of international student protests. Because student demands went beyond academic concerns to include calls for democracy and civil liberties, the 1968 movement was unprecedented. The protests revealed a public crisis of confidence in the Mexican government. Mexicans had come to see the divergence of the state’s policies from its revolutionary rhetoric of social justice. Young people protested for change.

Carey reveals how the student movement challenged gender norms and placed women into the public sphere as never before. Young, educated, middle-class women subverted traditional femininity as they engaged in public political discourse. Organizing protests and debating issues in public spaces traditionally reserved for men, female protesters constructed new identities and possibilities within the movement and in public and private life at large. Participant interviews demonstrate the significance of renegotiating gender roles among student protesters. After challenging the established gender order, many female protesters were forever changed; these women never again considered public life to be the exclusive realm of men. Carey contends that the mobilization of women in 1968 set the stage for a second wave of Mexican feminism in the 1970s.

Carey reveals how the student movement challenged gender norms and placed women into the public sphere as never before. Young, educated, middle-class women subverted traditional femininity as they engaged in public political discourse. Organizing protests and debating issues in public spaces traditionally reserved for men, female protesters constructed new identities and possibilities within the movement and in public and private life at large. Participant interviews demonstrate the significance of renegotiating gender roles among student protesters. After challenging the established gender order, many female protesters were forever changed; these women never again considered public life to be the exclusive realm of men. Carey contends that the mobilization of women in 1968 set the stage for a second wave of Mexican feminism in the 1970s.

Carey provides insight into the relationship between the individual and the state under the rule of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), which held power in Mexico from the late 1920s to 2000. She analyses the paternalistic language used by the PRI, which had cast itself as the protector of the Revolution and student protesters as unruly children needing to be brought back into the fold of the revolutionary family, thus revealing how the party conceived its sociopolitical role. This dynamic was both challenged and reified by the events surrounding the movement of 1968. The student movement represented a direct challenge to government paternalism, but was eventually suppressed, ultimately confirming the state’s position as head of the revolutionary family. Nevertheless, Mexican society was reshaped. The events of 1968 threatened the legitimacy of PRI rule as well as traditional notions of femininity. The impact of 1968 was still being felt in 2000, when a non-PRI candidate became president for the first time in over seventy years.

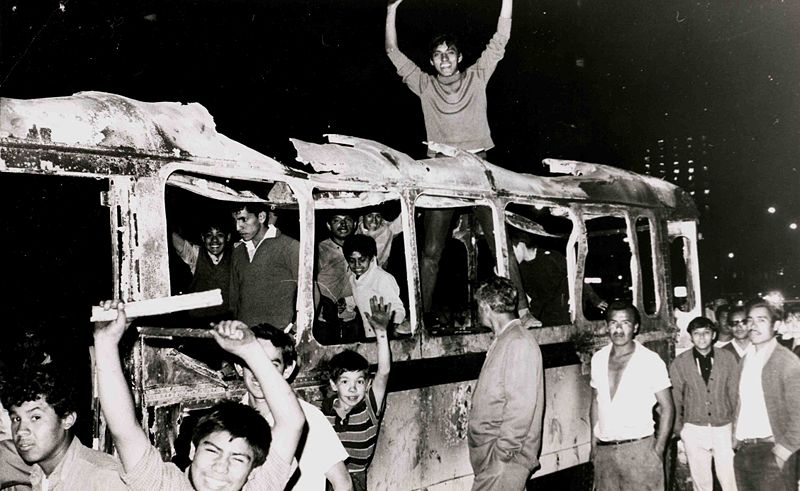

Student protesters in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas

Student protesters in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas

Carey’s approach sheds light on many important aspects of the student movement and its aftermath. Her sources include participant interviews, both conducted by the author and others, student and government propaganda, newspapers and other periodicals, novels, plays, poetry, music, films, and photos. Her detailed interpretations of visual media, including editorial cartoons and student propaganda, are particularly useful in understanding the nuances of government and student rhetoric. And, by tapping formerly unreleased U.S. and Mexican state records, Carey provides a valuable look past the government and student propaganda.

While a welcome addition to the historiography of modern Mexican history, Plaza of Sacrifices has some shortcomings. Carey’s emphasis on government control of the public response to the movement takes away popular agency, so the book misses a large aspect of the sociopolitical discourse related to the formation of this response. While government propaganda surely influenced the public, students and other ordinary people did find their own voice, as the large scale demonstrations show. Carey’s overwhelming support of the student movement comes across in her writing. For Carey, public opinion is either pro-student or influenced by government propaganda and pro-government. She could have explored more fully how public opinion was formed, giving more agency to the public.

Plaza of Sacrifices provides a valuable narrative of events surrounding the Mexican student movement of 1968. Accessible to both lay and academic readers, this book should be read by anyone interested in this important chapter of Mexican history.

Group photograph: Anonymous Mexican students on a burned bus, July 28, 1968.

Credit: Marcel·lí Perelló via Wikimedia Commons

You may also like:

John McKiernan-Gonzalez’s article Onda Latina The Mexican American Experience.