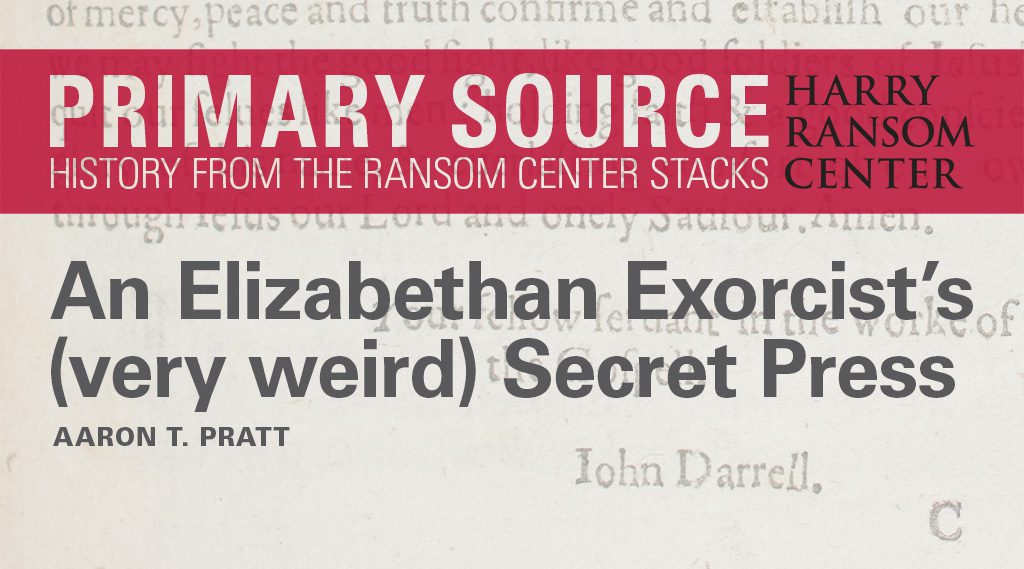

By Aaron T. Pratt

This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.

John Darrell’s run as a celebrity exorcist during the later 1590s began to go downhill after a young man he was treating in Nottingham accused the wrong person of witchcraft: William Sommers pointed to Alice Freeman, cousin of one of city’s highest-ranking officials, as the cause of his possession.1 Sommers’s sister chimed in, too, claiming that Freeman had previously killed a child of hers with black magic. Despite this two-pronged accusation, however, the charges didn’t hold up in court, and sentiment toward Darrell soured as many in town became skeptical about the authenticity of Sommers’ possession and frustrated with the disruptions the exorcist’s presence in the city was causing. Darrell’s efforts to dispossess Sommers and his fire-and-brimstone preaching had added a spiritual dimension to existing class conflict in Nottingham, inflaming the situation so much that authorities further south started to pay attention. Only a few months after Freeman was cleared and the spotlight had turned on him, Darrell wound up imprisoned in London awaiting prosecution in front of the High Commission, England’s top ecclesiastical court. The commissioners brought in Sommers and others Darrell had treated so they could testify that he had coached them to feign possession. At the close of 1599, Darrell was free again, but only after being convicted of fraud and stripped of his position as a minister. By that point, he’d spent around eighteen months behind bars and had his reputation tarred by the commission itself and, more lastingly, a major attack in print.

Samuel Harsnett, who was chaplain to the Bishop of London, led the High Commission’s prosecution and used the communication pathways of the book trade to take a shot at Darrell. Before a verdict had even been reached, he’d written A discoverie of the fraudulent practises of John Darrel Bacheler of Arts and worked with John Wolfe, a well-known London publisher, to have it printed. Harsnett would later follow up Discoverie with another work that condemned a series of Catholic exorcisms performed in Buckinhamshire in the 1580s: A declaration of egregious popish impostures (London: James Roberts, 1603). Shakespeare is known to have drawn on this second Harsnett book, particularly in his treatments of King Lear’s madness and, in the same play, of Edgar when he’s disguised as Poor Tom, a possessed beggar.

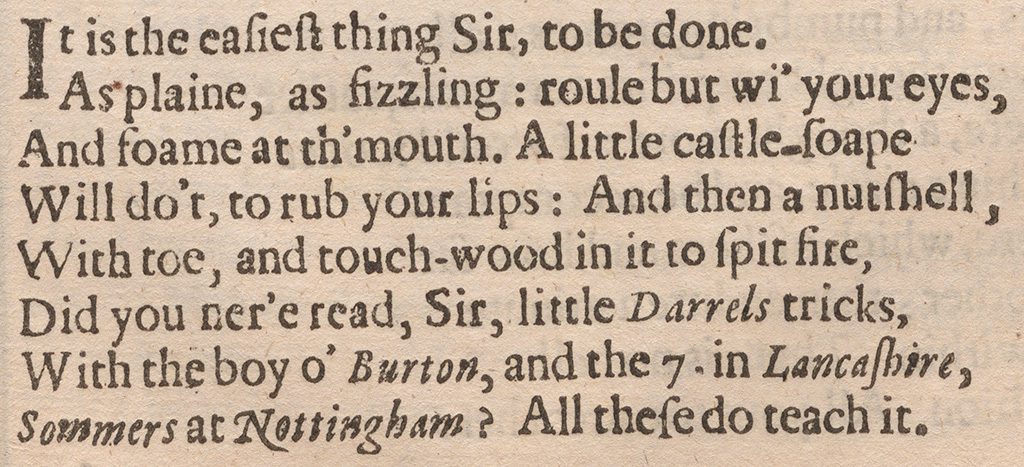

It’s in another and somewhat later play, though, that we see the impact of Harsnett’s book about Darrell’s “fraudulent practises.” In the final act of Ben Jonson’s The Devil is an Ass, which was written and first performed in 1616, a scheme by the con-artist Merecraft has been upended by a last-minute maneuver, and he comes up with a new plan to correct course and get control of the estate he’s been after. The idea is to convince his dupe, Fitzdottrel, to feign demonic possession and charge his own wife and her collaborators with witchcraft. In coaching Fitzdottrel on how to perform authentically, Merecraft asks him, “Did you ner’e [never] read, Sir, little Darrels tricks, With the boy o’ Burton, and the 7. in Lancashire, Sommers at Nottingham?” “All these do teach it,” he adds.

Merecraft’s characterization of possession symptoms as “little Darrels tricks” indicates that he believed the charges of fraud that had been levied against Darrell more than fifteen years earlier. His choice of a verb also tells us that he knew about the exorcist’s three most famous cases by reading rather than simply hearing about them. His source—and, by extension, Jonson’s—was almost certainly Harsnett’s Discoverie.

Darrell and his supporters, though, were no slackers when it came to taking advantage of print. In fact, Harsnett’s recourse to the press in the first place was prompted or at least hastened by books that began circulating while Darrell was still imprisoned and his High Commission case underway. As Brendan C. Walsh writes, “Aware that they had little opportunity to advance their cause through the courts, the Puritan network initiated what would become a lengthy print campaign” of their own.2 First came an anonymous defense of Darrell’s handling of the Sommers case. Then came two back-to-back tracts by Darrell himself, one an expansion of the other. Even though he was in prison, Darrell evidently had access to writing material and was able to get manuscripts smuggled out to publishers, perhaps with some money changing hands to encourage the jailer turn his head the other way.

But while Harsnett was able to work openly with London publishers to get his book against Darrell out, Darrell and his “Puritan network” had to get creative. Harsnett’s position on the High Commission had not only made him an “enforcer of conformity” in the courtroom, it also made him a censor responsible for approving—and rejecting—books for the press.3 In 1597, a pamphlet that detailed Darrell’s exorcism of the “Boy of Burton,” Thomas Darling, appears to have successfully received a license, but there was almost zero chance of anything sympathetic to Darrell scraping by again, not after the upheaval in Nottingham and the onset of his London trial. Instead, Darrell’s supporters had to work with presses abroad to get out the three pamphlets that preceded Harsnett’s Discoverie. Two were apparently printed in Amsterdam, the other by Richard Schilders in Middelburg; both cities were home to exile communities of English Puritans. Getting the books written while Darrell’s trial was underway and back to England in the form of printed editions before it had concluded was no small feat: the authors had to produce their texts, the original manuscripts had to be sent by ship to the European continent and printed, and then the printed sheets had to be packed up, shipped, and likely smuggled into England.

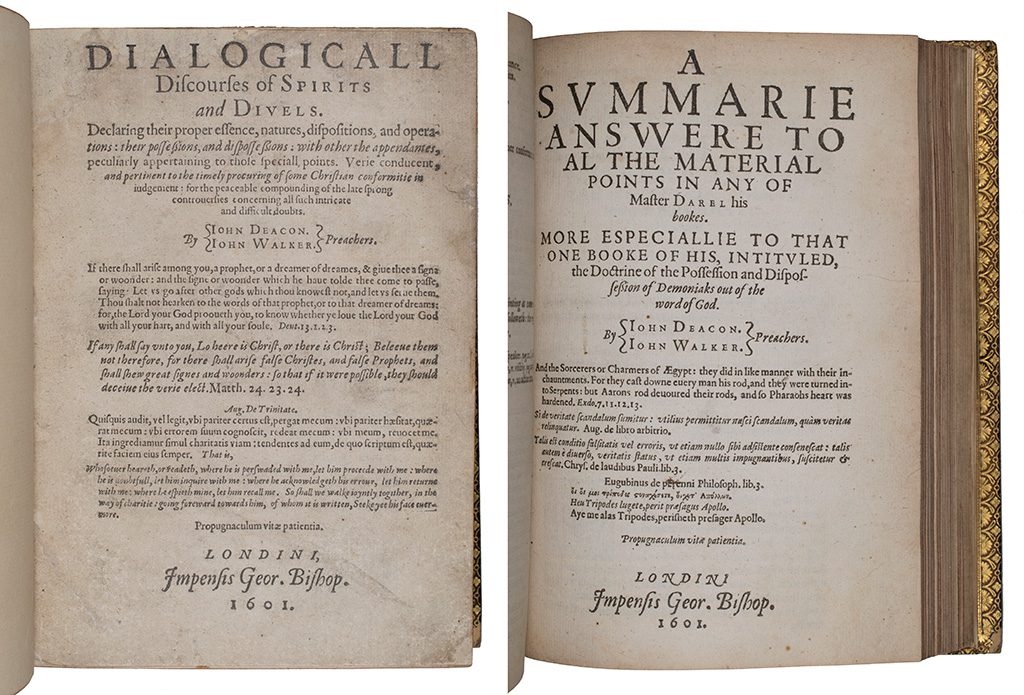

The imprint at the bottom of the title-page of Harsnett’s Discoverie unabashedly advertises where the book was printed, who printed it, and when. So, too, do the imprints of two books written against Darrell in the wake of his trial: John Deacon and John Walker’s Dialogicall discourses of spirits and divels and A summarie answere to . . . Master Darel his bookes. Both specify that they were published in London by George Bishop in 1601:

Informative imprints, of course, were perfectly standard, but not one of the books written by Darrell or his supporters during or after the High Commission trial advertises any origin whatsoever, foreign or domestic. We only have a sense of where they were printed because of painstaking work undertaken by modern bibliographers, researchers who have combed these books’ printed pages for clues that might help reveal where they’re from. For example, the very first pamphlet to come out of the trial—the anonymous defense of the Sommers case—features a decorative ornament on its title-page, one that also appears on the title-page of an unrelated book from 1597 that says it was “Imprinted in Amstelrodam [sic].” The ornament does not appear in the Darrell-authored book that’s been attributed to the same Amsterdam press, but both it and the anonymous pamphlet that inludes the ornament were printed with the same fonts and share design elements. And, helpfully, both make use of the same floriated capital W when spelling out “William Sommers.” Unfortunately, though, while the ornament match makes Amsterdam the likely origin of these two pamphlets, we still don’t know the specific identity of their printer.

With backstories even more mysterious are four editions of works by Darrell that were published, according to their title-page dates, after his case had concluded: two in 1600 and two in 1602. The same bibliographical authority that attributes the earlier tracts to continental presses suggests with some hesitation that all four of these later books were likely printed on a clandestine press that operated within England.4 The editions make use of the same roman and italic fonts and exhibit similar page design, but no one has yet been able to associate these editions with any other books or otherwise identify the press. All we know about the publication and early circulation of the press’s work is that one of the editions from 1600 was probably the “lately printed” book by “mr Darrell . . . concerning the casting out of Devilles” ordered burned by London’s Stationers’ Company on October 29th, 1600.5 But what’s the context for this order: Who wanted the book burned? How many copies did the trade organization have? How did it get them? Did the burning even take place?

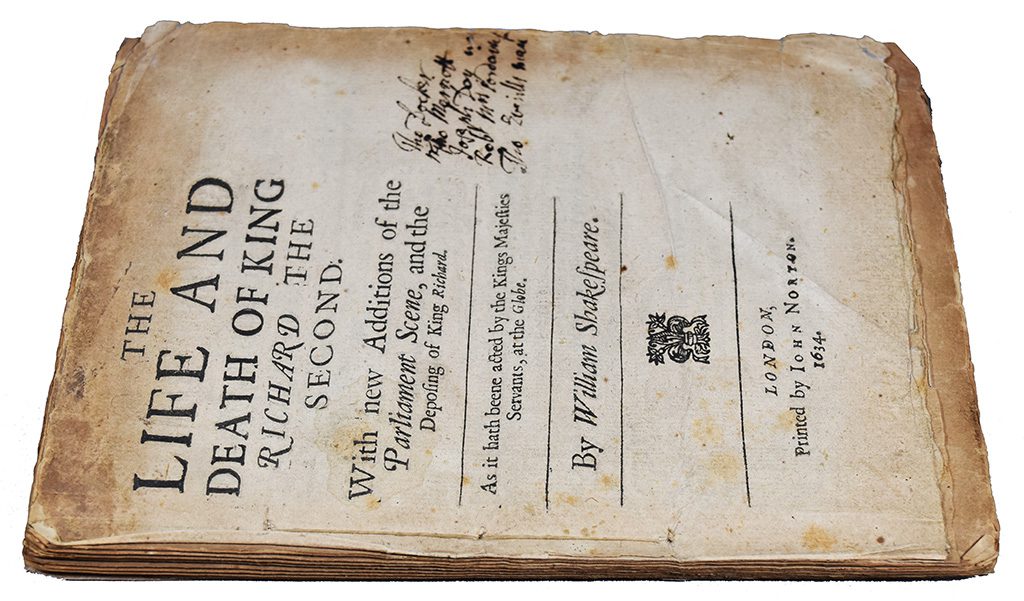

The Ransom Center has long held a rather curious copy of the edition that’s usually associated with the Stationers’ Company order, Darrell’s A true narration of the strange and grevous vexation by the devil, of 7. persons in Lancashire, and William Somers in Nottingham. While currently in a much later binding, holes in the inner margins of its leaves provide evidence that the copy originally circulated as a stitched pamphlet, just like other books its size and length usually did.

Somewhat bizarrely, though, three pairs of leaves from the same press’s other 1600 edition have been inserted into this copy, in three nonconsecutive places. Once page numbering starts in True narration, it proceeds straightforwardly from 1 to 90, but pages numbered 142–145 from that other book, Darrell’s A detection of that sinnful, shamful, lying, and ridiculous discours, of Samuel Harshnet, appear between 90 and 91. Its 146–149 are then between True narration’s 94 and 95; finally, 150 and the next three pages of Detection fall between 98 and 99 of True narration. The interloping leaves exhibit the same pattern of stitching holes as the rest of the volume, making it likely that they have have been in their current positions since the pamphlet was initially assembled at the beginning of the seventeenth century.

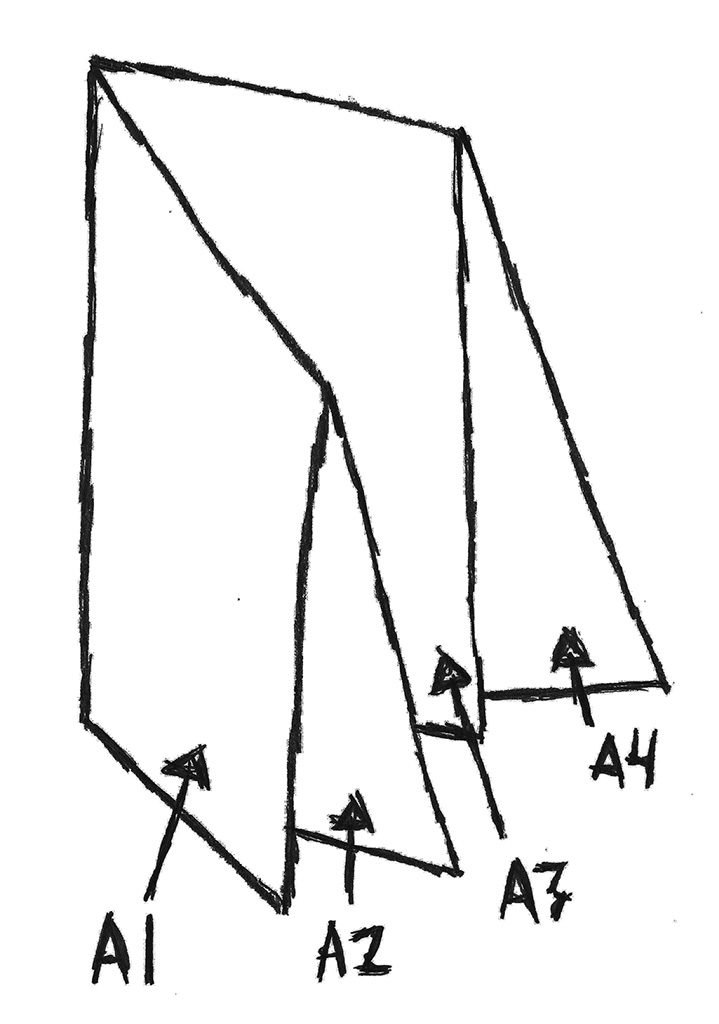

Clearly, page numbering cannot provide an explanation for why the extra leaves were inserted where they were, but page numbers were not what early modern bookbinders (or pamphlet-stitching booksellers) generally followed when assembling books. Instead, they relied on what are known as signatures, printed letters or symbols used to identify the leaves of gatherings, the individual folded units that together make up a book. All four of the Darrell pamphlets attributed to the secret English press are quartos: these are books where each sheet of paper handled by the printer ends up transformed into four printed leaves or eight printed pages. The most straightforward type of quarto is one where a single sheet of four leaves becomes a single gathering of four leaves after it has been folded twice:

In this diagram, the signature of the gathering is “A.” If the hypothetical sheet were from a typical English book printed in 1600, the first leaf would have “A” printed as a signature at the bottom of its first (recto) page. The same position of the second leaf would read “A2”; the third “A3”; and the fourth would be left blank. Then, the next gathering would begin with “B”; the third “C”; and so on.

In True narration, the “A” gathering follows the standard practice, with the first three leaves signed as expected. Things get irregular after this, though: only the first two leaves in the next gathering are signed, “B1” and “B2.” (Notice that the signature on the first leaf, atypically, includes both the leaf number, “1,” along with the gathering letter.) The same is true for the following gathering, “C.” Then the alphabet starts over with “A” at the beginning of a new section of the text, but this time the signing is a hybrid of what has come so far: the first three leaves of the next gathering are signed, as in the first “A” gathering, but the first leaf is now signed “A1,” with a number. This pattern then holds until we get to the “K” gathering. At this point, instead of continuing with standard quarto gatherings of four leaves, the book pivots to gatherings that are made of only two leaves each, or half of a quarto sheet. These continue for the rest of the book, through the “S” signature. In most of the two-leaf gatherings, both are signed with both letter and number, as in “O1” and “O2.”

It remains unclear exactly why leaves from Darrell’s Detection ended up with the Ransom Center copy of True narration when it was being assembled, but their placement isn’t random. Detection, it turns out, is even more eccentric than True narration when it comes to the ways its gatherings are signed. Like the final section of True narration, most of Detection is in two-leaf—or half-sheet—gatherings. There is an initial alphabet that’s mostly formed by half-sheets signed only on their first leaves. The first “O” gathering, for example, has “O1” on its first leaf and no signature on the second. After the first alphabet ends, however, another begins. In this one, the first leaf of the “O” half-sheet is signed “O2,” with its second leaf unsigned. There’s also a third alphabet of half-sheets that begins with one initially signed “A3” and ends with one that begins with “H3.” This, to put it simply, is very strange.

![John Darrell, A detection of that sinnful, shamful, lying, and ridiculous discours, of Samuel Harshnet ([England?]: n.p., 1600), sigs. "O2"1r and "O2"2r. Harry Ransom Center Book Collection, BF 1555 D377 1600.](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Primary-Source-2020-10-Image-07.jpg)

Normally, the numbers in signatures identify the position of a leaf in a gathering. Despite the anomalies in True narration, its signing at least adheres to this basic principle. In Detection, however, the numbers in the signatures on the first leaves of its half-sheet gatherings identify the whole gathering and not an individual leaf. With “A3” printed on the first leaf of a unit that’s made of only two leaves, there’s no other way to make sense of it. When they had exhausted a first run of the alphabet, printers’ standard practice across Europe was to begin the next sequence with “Aa.” Doubling letters like this allowed numerals at the end to continue serving the exclusive function of numbering leaves, saving booksellers and binders the confusion apparently faced by the person who assembled the Ransom Center copy of True narration. The three leaf pairs from Detection that appear in it are the half-sheet gatherings signed “O2,” “P2,” and “Q2.” Likely unfamiliar with the idea of an entire gathering that would begin with leaf signed with a “2,” our pamphlet-maker found the only place in True narration where they could go with any justification: nested in the middle of the two-leaf gatherings that begin with leaves signed “O1,” “P1,” and “Q1.” This way, the leaves with “2” signatures on the stray Detection half-sheets at least follow leaves signed with a “1.” Of course, the Detection half-sheets still don’t really make sense where they ended up—they are, after all, from a completely different book—but their presence in this one copy helps to highlight the weirdness of these later Darrell books at the level of the edition. It is difficult to understand exactly how and why they were printed the ways they were.

![John Darrell, A survey of certaine dialogical discourses and The replie of John Darrell, to the answer of John Deacon, and John Walker ([England?]: n.p, 1602), sigs. A1r and A1r, respectively. Harry Ransom Center Book Collection, uncataloged acquisition.](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Primary-Source-2020-10-Image-08.jpg)

The two 1602 books attributed to the secret press were written by Darrell in response to the volumes by Deacon and Walker mentioned above. Both are composed entirely of two-leaf gatherings. One, A survey of certaine dialogical discourses, is similar to Detection in that it includes many gatherings with numbers in the signatures that identify the gathering itself. That is, there are many half-sheets that begin with a leaf signed with a “2,” as in “B2,” “G2,” and “K2.” But where Detection puts the “2” gatherings back-to-back after the first alphabet ends—B2, C2, D2—Survey represents a new way of doing things: it puts them right after their corresponding “1” gatherings—B1, B2, C1, C2, D1, D2. Then, finally, A replie of John Darrell, to the answer of John Deacon, and John Walker is made of traditionally and straightforwardly signed half-sheet gatherings: the first leaf of each is signed simply with a letter, and the second is left unsigned.

All four of these editions demand further and more intensive analysis to better ascertain how they were printed, but the irregularity of the books’ structures—especially the structures of the editions from 1600—the press’s increasing reliance on two-leaf gatherings, and the idiosyncratic signing patterns of three of the four books support the conclusion that they were printed on an ad hoc clandestine press, perhaps one in a private English residence, and not by professional operation at home or abroad. Darrell may never have been able to pursue his exorcism ministry again, but the lengths that his supporters went to in defending both him and their collective cause demonstrate just how committed they were, even if we just focus on the labor and other resources required to defend Darrell in print. They worked with two different printers in Europe and may very well have invested in a press, type, and the other equipment necessary to ensure that Darrell’s writing was printed domestically and circulated widely. The more we learn about the nuts-and-bolts of the printing processes behind these books themselves, the better we will be able to see the efforts and creative problem-solving of Darrell’s allies.

And the secret press books survive reasonably well today. If any were, in fact, burned by London’s Stationers’ Company, the overall numbers must have been relatively small, because their survival rates compare favorably with the rates for similar books from the period, including Harsnett’s Discoverie. The two 1600 editions are now spread across US and UK libraries in what appear to be roughly equal numbers, adding up to right around fifty copies in research institutions. With the 1602 editions added—including a bound set of them that just entered the Ransom Center’s collection—the number jumps to more than eighty books from the press that have been preserved across the centuries and are available for study today.

Aaron T. Pratt is Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Curator of Early Books and Manuscripts at the Harry Ransom Center. In this role, he supports the Center’s wide-ranging and often deep collections of materials originally created before the eighteenth century. His own research focuses on the literature and culture of early modern England, bibliography, and the history of the book.

1 For the most recent reevaluation of Darrell and his career, see Brendan C. Walsh, John Darrell and the Shaping of Early Modern Protestant Demonology (New York and London: Routledge, 2021). I draw on this study, in particular, for information about and interpretations of Darrell’s cases and biography.

2 Walsh, 154.

3 Marion Gibson uses the phrase “enforcers of conformity” while discussing Samuel Harsnett in Possession, Puritanism and Print: Darrell, Harsnett, Shakespeare and the Elizabethan Exorcism Controversy (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2006), 63.

4 A Short-Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland, & Ireland and of English Books Printed Abroad, 1475-1640 (STC), 2nd edition, ed. A.W. Pollard, G. R. Redgrave, W. A. Jackson, F. S. Ferguson, and Katharine F. Pantzer, 3 vols. (London: Bibliographical Society, 1976-91).

5 Records of the Court of the Stationers’ Company, 1576–1602, ed. W. W. Greg and E. Boswell (London: Bibliographical Society, 1930), 79.

![John Darrell, A true narration of the strange and grevous vexation by the devil, of 7. persons in Lancashire, and William Somers in Nottingham ([England?]: n.p., 1600), sig. π1r. Harry Ransom Center Book Collection, BF 1555 D377 1600.](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Primary-Source-2020-10-Image-03-730x1024.jpg)

![John Darrell, A true narration of the strange and grevous vexation by the devil, of 7. persons in Lancashire, and William Somers in Nottingham ([England?]: n.p., 1600), sig. A1r. Harry Ransom Center Book Collection, BF 1555 D377 1600.](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Primary-Source-2020-10-Image-06-730x1024.jpg)