And I wish to add one more thing, if I can.

The Prime Minister died a happy man.

Farewell to the dust of my Prime Minister,

husband and father, and what’s rarely said:

son of Rosa the Red.”Dalia Ravikovitch, translated from the Hebrew by Chana Bloch and Chana Kronfeld

On November 4 of 1995, the Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin– “the beautiful son of the Zionist utopia” — was assassinated by Yigal Amir, a 25 year old law student and Jewish zealot. The assassin wished to thwart the peace process, led by Rabin, between Israel and the Palestinians. Twenty years after the assassination, the word “peace” seems to have evaporated from Israeli discourse as Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu promises his people will “forever live by the sword.” It is now crucial to reexamine the murder and its effect on the course of history, on the Arab-Israeli conflict and particularly on Israeli society. What role, if any, did the murder have on “the triumph of Israel’s Radical Right,” as the title of UT’s Professor Ami Pedahzur’s last book suggests?

Rabin became Prime Minister in 1992 with a promise to achieve peace between Israel and the Arabs. But for most of his life he was not a man of peace. In his teens, he joined a pre-state Jewish militia and later played a significant role in the Independence War of 1948. In his memoir, he writes frankly about the expulsion of Palestinian Arabs from the newly established Israel and his role in it. Rabin served another 21 years in the Israeli Army, becoming its Chief of Staff in 1964. He thus has a crucial role in Israel’s most famous military victory—the 1967 Six Day War, in which Israel occupied territories three times its original size.

Hence, for most of his life, Rabin was the ultimate embodiment of the Zionist ethos, a real Sabra—native born, socialist-secular educated, from Ashkenazi origins; he was a dedicated settler and a brilliant combatant. Later he would serve as ambassador to the United States, a member of the Israeli Parliament, Prime Minister, and Defense Minister. Beside the political ramifications of his assassination, the event also carries great symbolism. No leader represents the values of the old Zionist elite more than Rabin. His murder, in retrospect, symbolized the decline of liberal Zionism and the rise of a new radical elite.

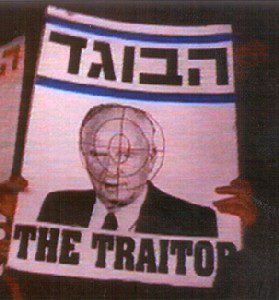

Although a small coterie was responsible for the murder, it came after a long campaign inciting violence against the Prime Minister, run by the political right and directed at Rabin, Shimon Peres, and the peace process. The writing was literally on the wall and I remember seeing it daily, with slogans like “Rabin is a traitor,” or “Death to Rabin.” Thousands of right wing demonstrators set fire to photomontages of Rabin wearing an “Arab” Kafyyia or dressed as an SS officer. The abuse of Holocaust discourse was especially common and obviously loaded. Historian Idith Zertal notes that “central Israeli political figures and parties, including two individuals who were later, as a direct or indirect consequence of the assassination, to become Prime Ministers [Netanyahu and Sharon], and past and present cabinet ministers, played an active role in these demonstrations.” Yet, to this day, the Right has managed to disassociate itself from the assassination.

At the funeral, Rabin’s widow refused to shake Netanyahu’s hand and told the press: “Mr. Netanyahu [the head of the Opposition] incited against my husband and led the savage demonstrations against him.” It is here where the story revealed itself as a biblical, or Shakespearean, tragedy. Seven months after the murder, Netanyahu came to power and systematically destroyed the already-broken peace process. In the aftermath, many Leftists (such as Rabin’s widow) invoked the biblical story of prophet Elijah telling King Ahab: “Thus saith God, Hast thou committed murder, then also hast thou inherited?”

Zeev Sternhell, a world expert on fascism, wrote: “Israel was the first democratic state—and from the end of the second World War, the only one—in which a political murder achieved its goal.” Amir did not murder Rabin out of personal hatred. In Amir’s own words, “It wasn’t a matter of revenge, or punishment, or anger, Heaven forbid, but what would stop the Oslo [Peace] Process.” Yet politicians from the Right have managed to de-politicize the murder. They now depict the assassin, along with his colleagues and their mentors — the very rabbis who “sentenced” Rabin to death—simply as “bad apples.”

Since any peace agreement would necessitate at least some withdrawal from the occupied territories, both the secular and religious Right fiercely oppose such plans. The moderate right-wing, led by Netanyahu, argues that such a withdrawal endangers Israel’s security; the religious also perceive any territorial concession to Arabs as a betrayal of God’s Divine Plan. Beyond Israeli objections, the Oslo Peace Process was rightly criticized by many Palestinians for promising them only autonomy, not statehood. An agreement that fell short of satisfying the needs of the Palestinians also far exceeded what the Jewish Right-wing could tolerate.

Under the Oslo Agreement, Israel has (partly and slowly) withdrawn from some parts of the biblical, Greater Eretz Israel. For many religious and messianic Jews, this meant a secular attack on God’s plans. Rabin’s murder, writes philosopher Avishay Margalit, “was not confined to a direct assassin or assassins. The murder of Rabin… was a statistical question – who will actually commit the deed.” And yet, the forces that abhorred any partition of the Holy Land have gained a historic victory.

There is no guarantee that Rabin could have achieved a just peace. Waves of Palestinian terror attacks eroded public support of the peace process already prior to Rabin’s death. There is also no guarantee that Palestinians would be satisfied with the very limited gains the Oslo Agreement guaranteed them. What we do know is that under Netanyahu’s first premiership (1996-1999) and under his successors, the peace process was utterly sabotaged. A new cycle of violence, the Second Intifada, began following the final collapse of peace talks in 2000. For many Israelis, the Second Intifada vindicated the right wing. The so-called “Peace Camp” — supporters of the two state solution — virtually disappeared.

Twenty years after Rabin’s assassination, Israel is run by the most right-wing government in its history. The victory of the right-wing Likud party in 1996, the evaporation of the Zionist-Left since 2000, and the ongoing de-politicization of Rabin’s death have empowered those against peace with Arabs. The assassin’s brother told the media last week that he is very pleased with the results of their deed. The ongoing attack by the Likud government on what is left of the Left might turn the Israeli ethnocracy, which privileges Jews, into a theocracy, which will represent the values and politics of the extreme right.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.