by Andrew Straw

Recalling his formative years as an American baby boomer and the influence the Cold War and the Soviet Union had on his worldview, Donald Raleigh asks what life was like for people his age in the Soviet Union? What were their concerns about the future? How did they spend their time and what did Cold War ideological battles mean for their daily lives? As historians exhaust the biographies and psychological studies of leaders to gain insight into authoritarian societies, scholars such as Raleigh are increasingly turning to evidence from everyday life to complete our understanding of non-democratic states. These new efforts are important because there is no denying  that authoritarian governments were common in the twentieth century, lasted for several generations, and some, like the authoritarian government of North Korea, continue to affect global affairs in the new millennium. It is also increasingly evident that popular participation, and not just dictators’ decrees, helped build and dismantle authoritarian regimes.

that authoritarian governments were common in the twentieth century, lasted for several generations, and some, like the authoritarian government of North Korea, continue to affect global affairs in the new millennium. It is also increasingly evident that popular participation, and not just dictators’ decrees, helped build and dismantle authoritarian regimes.

In Soviet Baby Boomers, Raleigh borrows the US term referring to children born after World War II to examine the Soviet Union. This Soviet cohort was born leading up to Stalin’s death in 1953 and during the transfer of power to a more reform-minded leader, Nikita Khrushchev. Unlike their parents and grandparents who experienced the horrors of revolution, two world wars, Stalin’s terror and disastrous modernization policies, this new Soviet generation grew up in the “normalized” Soviet Union. The secret police, one-party dictatorship, and communism remained, but surviving the Soviet system now meant finishing university dissertations, pursuing various personal goals, and using the black market economy to improve personal fortunes. In fact, Raleigh makes the important argument that “the Soviet System’s very success at effecting social change” caused the post-Stalin generation to become cynical about the system. The Soviet welfare state provided the foundation for an educated and urbanized professional class who supported reforms in the 1980s. By that time, the enthusiasm for a normal Soviet life had withered away as Soviet citizens were increasingly able to compare their standard of living to more robust Western economies, thus highlighting the absurdities of Soviet communism. And yet, most people were not active in the dissident movement throughout the 1960s and 1970s despite widespread sympathy for it. It was not until Mikhail Gorbachev initiated the policies of “glasnost” (openness) and perestroika (economic liberalization) that the baby boomers expressed their revolutionary ideas in public, elected officials that took reforms farther than Gorbachev imagined, and prepared as best they good for the positive and negative consequences of the market economy and democracy.

Raleigh’s research centers on students who graduated in 1967 from two magnet secondary schools that specialized in English in Moscow and Saratov. Through interviews, the author examines how these students experienced events in post-Stalin Russia such as Khrushchev’s liberalization after 1956, the Cold War, the Brezhnev “stagnation,” the Soviet-Afghan War, and Gorbachev’s reforms. Many of Raleigh’s discoveries might surprise American readers. For example the interviews reveal an almost total lack of “true communist believers.” Many respondents simply claimed that by the 1970’s any sensible person could see the economic absurdities in the communist system. Simultaneously, Western popular culture, from the Beatles to consumer goods, strongly influenced Soviet knowledge of the outside world and conflicted with negative portrayals of the West. Yes, students still had classes on Marxism, but the attempt to “brainwash” Soviet baby boomers failed. Official decrees and the aging Politburo were the target of popular humor that exposed Soviet absurdities; Westerners were not the only ones to poke fun at Brezhnev. The Communist Party continued to play a role, but several interviewees claimed that they joined the Party only because of career opportunities and the residual fear of the state police and prison camps. At the same time, many admitted that they probably could have had successful careers if the hadn’t joined the Party.

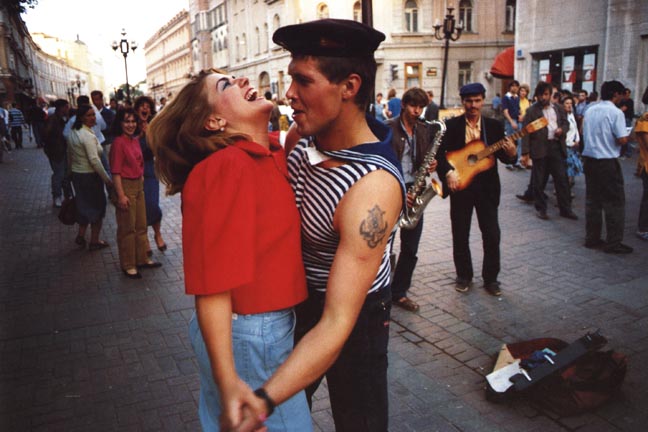

Street life in the Soviet Union, 1955 (Image courtesy of flickr/Malmo Museer)

Many of the interviewees are nostalgic about the past. A majority fondly remembers the good aspects of the Soviet welfare state (free education, medicine, housing, summer camps), especially when compared with the economic and social disasters of the 1990’s. Raleigh does an excellent job displaying how nostalgia is tied to the reasonable expectations of any modern welfare state and does not indicate that baby boomers would like to return to the Soviet-style governing. However, when asked about Vladimir Putin’s presidency, most interviewees spoke positively about the ex-KGB officer’s stabilizing effect on Russia since 2000. Raleigh also examines some of the darker memories of this period, such as the prevalence of Soviet anti-Semitism in society. For example, Soviet Jews were often overrepresented in the top primary schools when compared to other ethnic groups, but then experienced discrimination when applying for university or searching for a job.

The limit of Raleigh’s study is clear from the beginning: the group of students he selected to interview comes from the well-educated Soviet elite in two central cities. This limits Raleigh’s ability to draw larger conclusions about Soviet society and the reader is left wondering how commonplace such experiences and sentiments were for other Soviet citizens. The late 1940s, 50s and 60s were years of massive migration to the urban centers, but the book focuses on well-established urban families and does not offer any contrasting experiences of first generation urbanites. At other points, Raleigh highlights interesting facts, such as the underrepresentation of Tatars in Saratov schools, but then provides no explanation.

Muscovites street dancing in 1991 (Image courtesy of Abbeville Press)

In his defense, Raleigh readily admits the limitations of his sample of interviewees, and does an excellent job showing the differences between life in Moscow (the Soviet capital) and Saratov (a large, provincial city that was purposely closed to the outside world). Furthermore, the author argues that this elite cohort of students had a privileged place in Soviet society that made their actions key to giving Gorbachev’s reforms momentum. Another issue that oral histories inevitably invoke is the fact that interviewees’ memories of events change over time and people often lie. Raleigh responds to this point by asserting that he is not only interested in the facts of Soviet life, but in what the Soviet Union represents in the baby boomers’ memories today. He carefully interrogates suspicious responses to draw out misrepresentations of certain events or topics.

In sum, for Soviet historians the author provides a vital starting point for further research and comparison on Soviet life after Stalin. For the casual reader, Raleigh demonstrates how people lived their lives under an authoritarian state by maneuvering within the bureaucracy, sustaining their families, enjoying the comforts not available to earlier Soviet generations, and placing themselves in the position to help dismantle their authoritarian state.