Flip through the pages of almost any American history textbook. Within the first few sections, you will find paragraphs dedicated to the American Revolution and the ideological groundwork that supported it; the pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps mythology that surrounds Abraham Lincoln; the rise of a cotton-based economy in the South and the enslaved manpower that sustained it; the westward expansion of the American population and the lines of communication and transportation that they created in the wake of their migration. Fast forward to the twentieth century and that same textbook will likely devote space to the Manhattan Project, the Civil Rights Movement, and, perhaps less commonly, the country’s increasing reliance on foreign oil. In The Republic of Nature, Mark Fiege ambitiously attempts to reconceptualize this well-traversed historical terrain, first and foremost, as “a story of people struggling with the earthy, organic substances that are integral to the human predicament.” In each chapter, Fiege uses his riveting storytelling abilities to show that the nation’s history “in every way imaginable – from mountains to monuments – is the story of a nation and its nature.”

transportation that they created in the wake of their migration. Fast forward to the twentieth century and that same textbook will likely devote space to the Manhattan Project, the Civil Rights Movement, and, perhaps less commonly, the country’s increasing reliance on foreign oil. In The Republic of Nature, Mark Fiege ambitiously attempts to reconceptualize this well-traversed historical terrain, first and foremost, as “a story of people struggling with the earthy, organic substances that are integral to the human predicament.” In each chapter, Fiege uses his riveting storytelling abilities to show that the nation’s history “in every way imaginable – from mountains to monuments – is the story of a nation and its nature.”

The Republic of Nature challenges the historiography that relegates environmental history to the margins of key episodes in the nation’s history. By locating “nature” in some of the more familiar narratives of the American past, he forces his reader to ask what role nature plays in history and how the answer to that question shifts our understanding of human actions, interactions, and reactions between groups and with their environment. For instance, Fiege’s argument about the nature of slavery – namely that the driving force behind the institution was the marriage of plants and people – forced this particular reader (who considers herself at least somewhat familiar with American slavery) to rethink my understanding of the peculiar institution. Instead of a capitalist society in which commodification of the enslaved human body constituted the prime motivations of the master, Fiege recasts this familiar story as a power struggle between human (master) and plant (cotton) in which masters often failed to control the plant and thus transferred that loss of power to their slaves by more tightly controlling their lives and the productive abilities of their bodies.

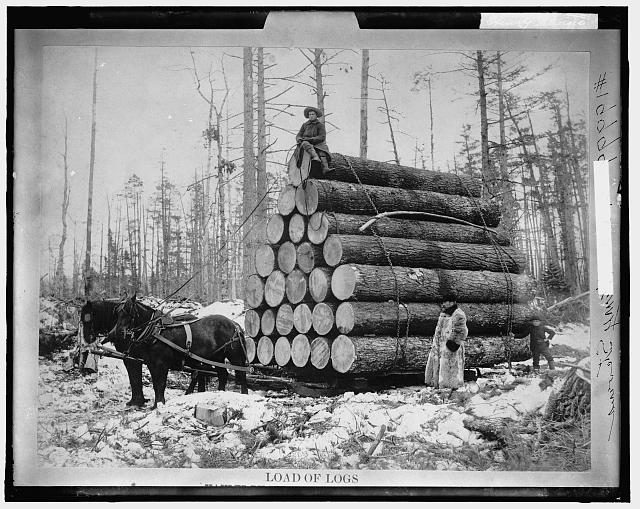

American loggers, 1908 (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Cotton farmers in the American south sometime between 1880 and 1897 (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

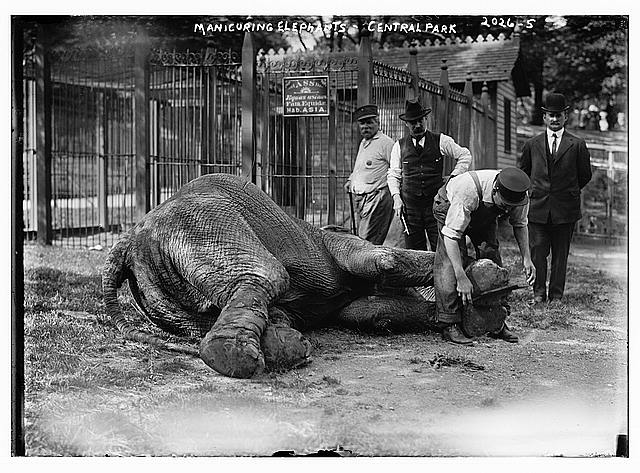

Workers at the Central Park Zoo in New York City manicure an elephant, date unknown (Image courtesy of the Library of Congress)

As title clearly indicates, Fiege’s work is limited to the history of the United States. It is interesting to consider how his work could be expanded beyond national borders to include the transnational perspective that is beginning to permeate the historical discipline. Fiege’s decision to write from a national perspective, however, produced a book that locates “nature” in varied contexts in order to unmake the familiar and remake it with an environmental focus. Occasionally, in the sweeping scope of his scholarship, the notion of “nature” becomes fuzzy as he attempts to thread it through such disparate events over a substantial expanse of time. With those minor criticisms in mind, this reader will still take distinguished environmental historian William Cronon’s word for it: “No book before it has so compellingly demonstrated the value of applying environmental perspectives to historical events that at first glance may seem to have little to do with ‘nature’ or ‘the environment.’ No one who cares about American history can ignore what Fiege has to say.”