Hoof Beats: How Horses Shaped Human History is an ambitious project that sets out to present a narrative of human-horse interactions in every corner of the globe from the deep evolutionary past to the twenty-first century. The result is a lucid survey drawing on fresh archaeological research—including some by the author—as well as interdisciplinary insights from oral history, linguistics, and veterinary medicine. The book is a pleasure to read and beautifully presented, with delightful in-text illustrations and 20 full-color plates. Blending erudition and accessibility, Taylor demonstrates the absolute centrality of horses to human cultures, economies, and technologies, as access to horses and expertise in horsemanship repeatedly shifted geopolitical balances on the broadest scale. Though one study cannot exhaust the interpretive potential of this material, Hoof Beats is an indispensable guide to the contours of the human past as they were drawn through contact with horses.

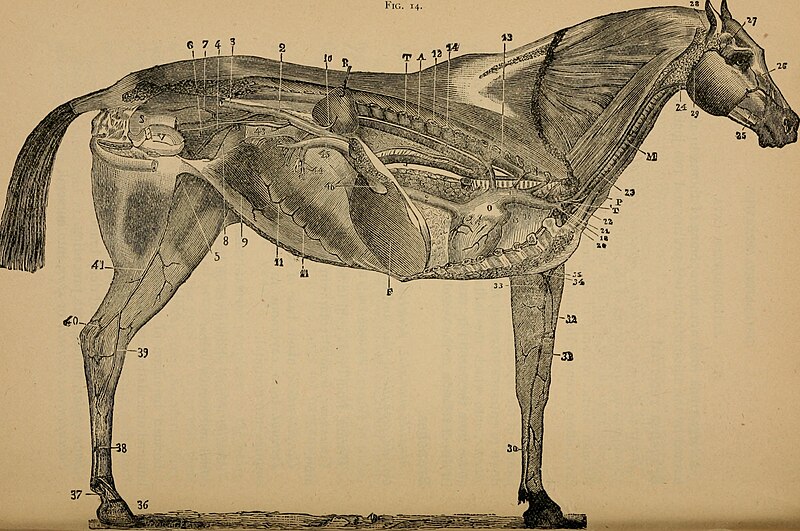

The book is divided into four parts, each referred to as a ‘beat.’ Beat One is dedicated to early connections between horses and people before domestication. Ancestral equids first evolved in North America approximately four million years ago and spread to Eurasia by the Bering land bridge. North American equids did not survive the warm conditions of the early Holocene, so our first evidence for interactions with hominins comes from the eastern hemisphere. According to archaeological remains of slaughtered animals in their grassland habitats, our ancestors were preeminent hunters of equids, including early horses and a separate lineage of donkeys and related animals. Taylor’s own research focuses on the domestication of horses, and he skillfully guides readers through the archaeological debate about when and where this first happened. He explains that research on domestication is not “a search for any particular trait or behavior but instead…a deep dive into the relationship between humans and animals and how it has changed over time.”[1] This relationship is clearly perceived by pathological changes or damage to a horse’s skeleton caused by bridles, mouthpieces, or the direct impact of a rider’s body.

Beat Two begins with an analysis of donkeys as the first domesticated equids. Taylor shows that evidence for their domestication can be found in early dynastic Egypt, where the “vertebral deformation” of donkey skeletons along with iconography depicting the animals hitched to carts suggests that they were widely used.[2] The cart and later the chariot spread throughout the Near East by donkeys and their hemione relatives. New research shows that this technology was eventually applied to domesticated horses in the early second millennium BCE by the Sintashta culture, along the border of what is now Russia and Kazakhstan. Burials including horses, chariots, and the world’s oldest bridles and bits provide conclusive proof of horse domestication and use in transport. The chapter shows how horse-drawn chariots spread rapidly across Eurasia in just a few centuries while also revolutionizing pastoral life in the steppes, encouraging greater mobility and larger herds. Especially in the Mediterranean world, horse-drawn chariots became the key to political and military power.

In Beat Three, Taylor describes the shift to horseback riding, a practice likely pioneered around 1000 BCE in what is now the Xinjiang Province of China. Evidence for riding in the area comes from whips, saddle pads, and notably “the world’s oldest trousers,” uniquely suitable for sitting astride a horse.[3] Though Taylor considers mounted riding across African and Eurasian societies in this section, the real protagonists are steppe cultures, especially from Inner Asia. People of the steppes drove “technological progress,” developing the frame saddle, stirrups, and curb bits.[4] They were well positioned to dominate the supply of horses, which were always in demand by surrounding civilizations. Taylor’s insights on the crucial role of horses and climate changes in the extraordinary success of steppe empires—from the Xiongnu to the Mongols—serve as much-needed context for the radical impact of these supposedly marginal societies.

Source: Rijksmuseum

Finally, Beat Four explores the global expansion of horses and horsemanship. Many Eurasian societies developed shipbuilding technologies to transport horses by water, leading to herds in Japan, Iceland, and beyond. Taylor is particularly interested in the “return” of horses to their distant homeland with the advent of European colonization in the Americas.[5] He demonstrates that archaeology can modify historical timelines for the spread of horses and their adoption by Indigenous societies. More importantly, in the Great Plains and elsewhere, he argues that “the rapid emergence of strong relationships between people and horses disrupted the trajectory of European colonialism and helped sustain the sovereignty of Indigenous nations deep into the modern era.”[6] This section concludes with a brief discussion of the fate of horses in the industrializing world—a story of intensified labor and, finally, marginalization.

Taylor is a skilled writer and a superb science educator. Hoof Beats can serve as a kind of primer in archaeological research methods for non-specialists. No region of the world remains untouched by his judicious treatment, making the book an excellent reference text and catalyst for further research. His incorporation of interdisciplinary material is impressive, but it is worth noting that he does not engage with critical animal studies (CAS) or historiographical approaches to animals.[7] This is understandable considering his disciplinary expertise and the goals of his project, but readers could be excused for coming away from his work with the assumption that horses exist for humans. Indeed, while Taylor proposes a relational model for human-horse history early in the book, his narrative actually prioritizes the human use (and, to a lesser degree, care) of horses. It would be worthwhile to flip Taylor’s perspective by taking a non-anthropocentric stance. For example, what can archaeology and veterinary medicine tell us about the quality of life for domesticated horses across time and space, whose skeletal remains seem to tell a constant tale of over-exertion and bodily harm? Taylor concludes his book by gesturing to the lessons for our modern world from the more sustainable, “golden age of horse transport.”[8] But for horses, this was clearly no golden age. Perhaps there are other lessons to be learned from this history.

Hannah McClain is a third-year PhD student in UT Austin’s Department of History. She studies early modern Europe with a regional focus on the Kingdom of Naples and Sicily.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

[1] Hoof Beats, 31. Italics in the original.

[2] Hoof Beats, 65.

[3] Hoof Beats, 113.

[4] Hoof Beats, 150.

[5] Hoof Beats, 180.

[6] Hoof Beats, 193.

[7] Readers interested in these alternative approaches can begin with Erica Fudge’s theoretical and methodological reflections in “A Left-Handed Blow: Writing the History of Animals,” in Representing Animals, ed. Nigel Rothfels (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002), 3-13.

[8] Hoof Beats, 219.