Martín Bowen’s most recent book, The Age of Dissent: Revolution and the Power of Communication in Chile, explores the turbulent period between 1780 and 1833 in which the inhabitants of the Captaincy General of Chile, a sparsely populated Spanish colony on South America’s Pacific Coast, witnessed an unprecedented scale of political experimentation and mobilization. Beginning in 1780, a series of plots, revolts, and a brutal civil war initiated in 1816 culminated in the collapse of Spanish rule and the emergence of Chile as an independent republic. In this context, women, artisans, indigenous, and free and enslaved peoples of African descent participated in the emergence of a pluralistic political landscape in which radical political dissension became an inescapable part of politics.

Drawing from archival repositories in Chile, Argentina, and Spain, The Age of Dissent skillfully uses newspapers, congressional debates, court cases, travel accounts, and material culture such as badges, flags, portraits, and other insignia to interrogate the ways in which Chileans from different social backgrounds experienced and participated in the desacralization of royal authority and the opening of politics. The book’s central claim is that this process was marked in large part by the emergence of radical political dissent and the appearance of new mediators in the political sphere. Bowen points out that while a diversity of opinions existed before the monarchical crisis, Chileans started to question the sacred foundations of royal power in this period by publicly expressing dissenting ideas about the legitimacy of the king and his agents.

The definition of radical political dissent used in the book is broad and incorporates a series of practices used by different actors to express disagreement either with the foundations of the ancient regime’s political power or with the ideas of republicanism. Thus, the realms of communication and visibility became the prime means to express radical political dissent. Dressing, iconoclasm, and rumor, alongside other written and discursive practices, were used by patriots and royalists alike to achieve their political goals.

The Age of Dissent is divided into two parts and eight thematically organized chapters. The first part explores how visibility became a realm of political action in Chile during the monarchical crisis. According to Bowen, insignia such as badges, clothes, and portraits were meant to manifest the transcendent origin of the political power of the monarch and his agents. However, after 1808 using the same insignia could potentially become a medium to express radical political dissent. For instance, chapter two analyzes the contested meaning of clothing during the revolutionary and post-revolutionary periods. Clothing, broadly defined to include hats, canes, and capes, represented the “natural” social hierarchies of the ancient regime societies. In Chile, sumptuary clothing was reserved for the elites, and popular was banned from their use. Nonetheless, patriots inverted the meaning of clothing by using hats or ragged clothing as republican symbols. Similarly, chapter four demonstrates how acts of iconoclasm, for instance, the destruction of portraits of King Ferdinand VII, were used to transgress the traditional boundaries of political participation.

The book’s second part is concerned with what Bowen defines as the “field of propagation”. In these chapters, Bowen reconstructs in great detail how, during the Age of Revolutions, Chileans believed that actions and behaviors, vices and virtues, could easily propagate throughout the social body via imitation and contagion. In this context, the elite’s behavior was thought to influence popular classes. Chapter Five explores how patriots invented new models of heroism during the Revolutionary period to destabilize traditional conceptualizations of heroism and loyalism. Following a similar line, chapter six explores how certain political ideas were thought to be vectors of contagion and how political actors in Chile used different forms of communication to spread dissenting ideas.

Notably, the book develops a rich conceptual frame to understand political action during the revolutionary and post-revolutionary periods. Categories of analyses such as “mimesis,” “publicness,” and “contagion” allow Bowen to capture the period’s social and political language, serving as an explanatory framework to understand how actors made sense of their actions. Furthermore, The Age of Dissent skillfully shows the complexity of the political landscape of revolutionary and post-revolutionary Chile, avoiding overly simplistic characterizations of the political actors. For instance, it shows that radical political dissent could be present within the same political factions.

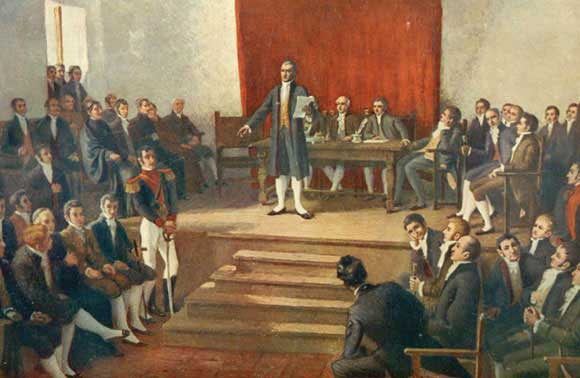

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Another important historiographical contribution is that the book places Chile in the wider context of Atlantic revolutionary politics. Often characterized as a backwater of the Spanish empire sheltered from the political agitation of the period, Bowen shows that Chileans were in close contact with revolutionary developments in the Atlantic World via the circulation of people and information. Bowen further stresses this point by analyzing a series of vignettes intertwined within the chapters of the book, such as the official celebration of US independence in Santiago on the fourth of July of 1812 or the arrival of Fernando Condorcanqui, the eldest son of Túpac Amaru II, to the port of Talcahuano in 1784.

The Age of Dissent is a welcomed contribution that adds to recent studies on popular politics, the public sphere, and the crisis of colonial rule in Spanish America. Furthermore, it expands our understanding of how communication and visibility became important tools that Chileans used to shape the transition from colony to republic. Nonetheless, the book lacks a detailed explanation of the origins of political dissent. Why did some political actors choose to side with the royalists or patriots? Did elements such as geography, literacy, or class shape this process of self-identification? Overall, The Age of Dissent’s captivating narrative and creative use of primary sources make it a compelling reading not only for scholars of Chile but also for anyone interested in the Age of Revolutions.

Juan Sebastián Macías earned a BA in History from the Universidad de los Andes (Bogotá, Colombia) and an MA in Latino/a and Latin American Studies from the University of Connecticut. Currently, he is a first-year PhD student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. His research interests include indigenous history and popular politics in the Northern Andes during the Age of Revolutions.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.