This review is part of the wider IHS Climate in Context Series. For more content, see here.

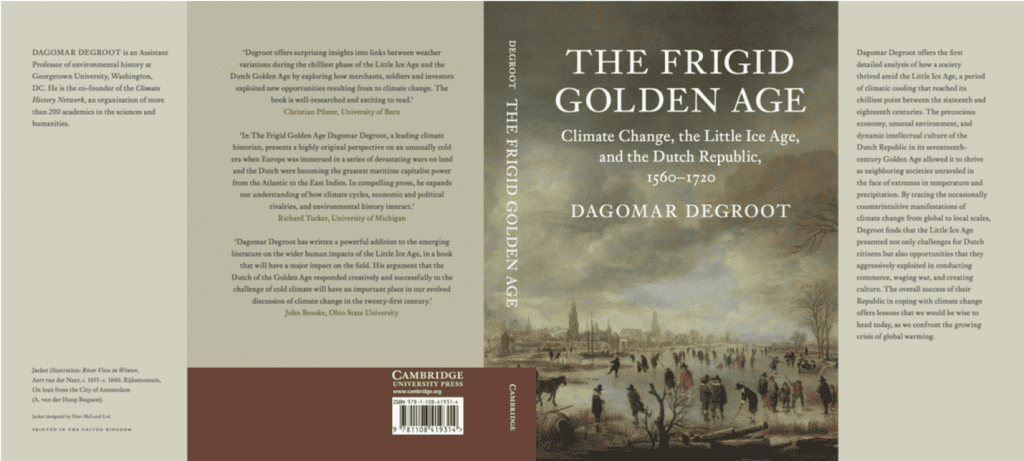

As the world struggles with unpredictable weather patterns and unstable food supplies caused by the current climate crisis, many have turned to the past for answers. Climate change is not new to human history. The Earth experienced a global drop in temperatures starting in the thirteenth century and continuing into the mid-nineteenth century, known as the Little Ice Age. Books on the Little Ice Age, such as Geoffrey Parker’s The Global Crisis, often highlight how the Earth’s cooling climate wreaked havoc on societies around the world as people struggled to adapt. Dagomar Degroot’s The Frigid Golden Age deviates from this standard narrative. He argues, instead, that the Dutch Republic, now the country of the Netherlands, actually flourished during, and even in part because of, the Little Ice Age.

Degroot explores how the years from 1560 to 1720, a period often referred to as the Dutch Golden Age, the Dutch Republic experienced an era of relative stability and strong economic growth that, counterintuitively, coincided with the coldest decades of the Little Ice Age. Did the Little Ice Age create climatic conditions that allowed the Dutch to flourish? Degroot stresses that correlation does not necessarily imply causation. He highlights that the reasons behind Dutch prosperity were complex and tied to a variety of factors that were also independent of fluctuating weather conditions. He admits, however, that the cooler temperatures did prove advantageous for the entrepreneurial and resilient Dutch.

Thus, as societies across the early modern world struggled to cope with cooling temperatures and decreased crop yields, Dutch society remained largely malleable to these changes and, at times, took advantage of them. For example, the changing climate shifted sea ice that facilitated their exploitation of Arctic resources, produced adverse weather conditions that aided in important Dutch military victories against English and Spanish forces, and influenced Dutch culture through the emergence of winter landscape paintings depicting the consequences of the Little Ice Age.

For the majority of his book, Degroot examines the effects of the Little Ice Age on Dutch commerce, conflict, and culture. He examines how the changing climate affected each of these aspects of the Dutch Republic by applying a three-part method. In using this methodology, he convincingly addresses the issues of scale and causation when connecting climate trends to human activities.

In the first step of this method, he determines how long-term global climate changes influenced local environments across short timeframes. For example, he highlights how cooling temperatures across northern Europe increased the frequency of autumn storms in the North Sea. Second, he uncovers examples of short-term, local environmental changes that affected human activities on similar temporal and geographic scales. For instance, and in connection with his discussion of Dutch commerce, he discovers that more shipwrecks often coincided with stormy autumn seasons. Degroot, however, notes that large, ocean-going Dutch merchant ships often survived the storms and in turn used the storms’ powerful winds to shorten their journeys. In his final step, he establishes the relationship between climate change and human history over long timeframes and large geographical areas. For example, while the increased frequency of storms also increased the risk, and thus the cost, of traveling on the North Sea, they also sped up the journeys of Dutch ships, increasing efficiency and decreasing the amount of time sailors were exposed to the deadly elements. His innovative methodology allows him to parse out how the Little Ice Age influenced how the Dutch conducted commerce, waged war, and responded culturally to climate change.

The Frigid Golden Age is a detailed, empirical study that brings to light the ways in which the Dutch Republic adapted to the changing climatic landscape of the Little Ice Age. Degroot draws on an expansive array of evidence, from ship logs to landscape paintings to tree ring analyses to depict the complex nature of Dutch society and its relationship with a changing climate. His work provides a refreshing perspective on the Dutch Golden Age by focusing not only on merchants and political figures, but also on farmers, craftsmen, and soldiers that comprised the Republic’s cosmopolitan nature.

Degroot offers a rich and valuable contribution to the scholarship on the Little Ice Age and climate history more generally. Written in clear and lucid prose, he generally maintains a fine balance between detailed forays into paleoclimatology and engaging vignettes through a thoughtful analysis of his sources. His work successfully challenges the reader to scrutinize human activity in the face of climate change and provides an innovative framework to explore the effects of climate change and how societies can adapt to changing environmental circumstances. The Frigid Golden Age is a must-read for those interested in climate history or early modern Dutch history, and for anyone broadly interested in the implications of climate change on human societies.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.