I learned a few months ago that the old Star Seeds Café near the UT campus had been demolished, a casualty of the I-35 expansion project. I was sad about this not because I miss the food—the old Star Seeds was always an acquired taste. My sense of loss, rather, has to do with the fact that the Star Seeds Café had been at the nexus of important professional and personal roads for me since my early 20s. And I have never attended the University of Texas as a student or lived in Austin. This requires some explanation…

I am a professional historian. I’ve taught at Portland State University in Oregon, down the highway at Texas A&M University, and, since last fall, have begun what I expect will be my final faculty position at the University of Texas at Austin. So this is an interesting time for me, one of reflection. At the age of 54 after more than three decades of a professional career studying U.S., Mexican American, and Texas history at these other institutions, these days I find myself spending a good deal of time learning how things work at my new university, where to go, and building relationships with a lot of new folks in and out of Garrison Hall.

As exciting as it is, this newness can also be humbling. For example, I participated in a faculty orientation process before fall classes began. This old dog was eager to learn new tricks. In those training sessions I distinctly remember a presenter chuckling about the first time they experienced the “passing period.” I had no idea why everyone thought this was funny, though context clues told me it involved students leaving class early. Oh well, I thought, each school has its own traditions. I resolved to be on the lookout for this so-called passing period on my teaching schedule, did not see it, and felt relieved—too bad for all those other suckers whose classes abutted this mysterious time! And then on my first day, I found out what it really was and how class times really worked. I had a chuckle…this time at myself. I’ve had additional little, surprising revelations in my new job, none of them quite so foolish. This is all a part of joining a new university, a universal experience for all faculty. And yet, I am in a slightly different position in that I’ve known this place in an entirely different context for decades. In fact, I’ve been coming to the University of Texas at Austin (and the Star Seeds Café) for over 30 years. The road to my historical research runs through this place.

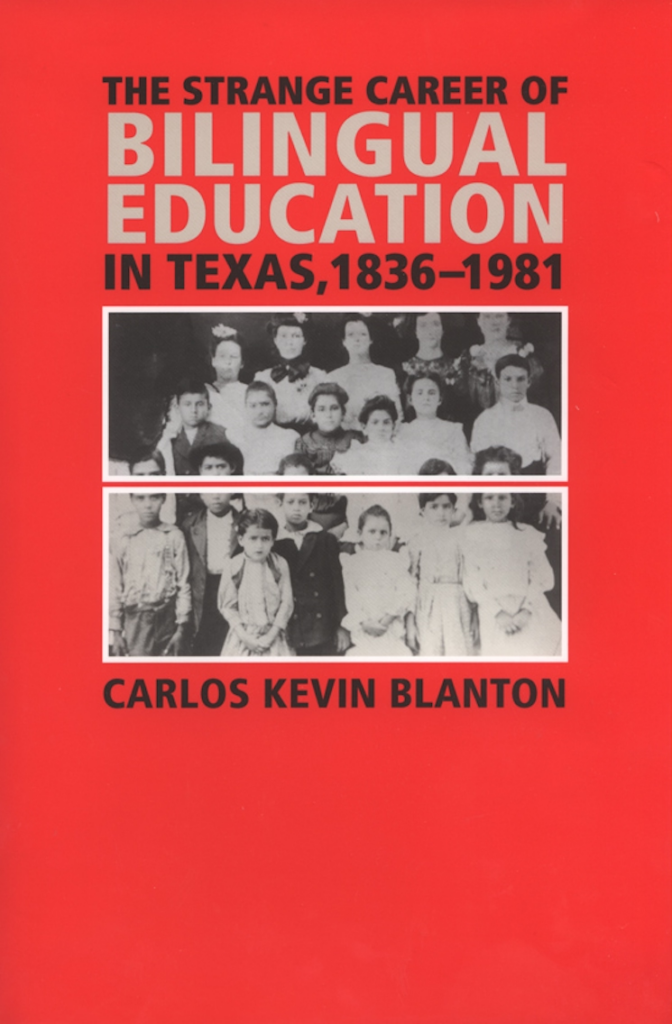

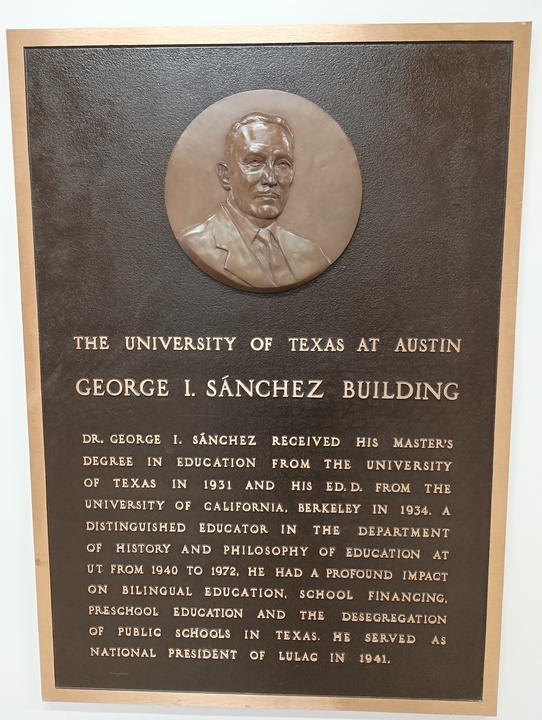

As a historian of U.S., Mexican American, and Texas history, I have visited libraries and other archival repositories all over the country, though none so often and so deeply as the places of learning on this campus. The products of this research are my published books and essays. My first major research project, an extension of my Rice University dissertation, was a study of education policy and bilingualism in Texas schools. This resulted in some published essays in academic journals as well as a book, The Strange Career of Bilingual Education in Texas, 1836–1981 (Texas A&M Press, 2004). My next major project was a biography of the famed University of Texas educator and civil rights advocate, Dr. George I. Sánchez, whose name graces UT’s College of Education building. That project resulted in another book, George I. Sánchez and the Long Fight for Integration (Yale University Press, 2014). All told I’ve authored over 20 essays in books, journals, or magazines and edited one other book, but it is those two major projects that have cemented my longstanding connection to this university and the treasures in its libraries. In all this work I find hidden, obscured voices of the past and bring them to light; I study not just conflict and injustice, but also the passion and joy that infuse those who try to make their worlds better places; I connect the dots between past and present, always believing that our shared future can be positively shaped by studying our shared past. It’s hard not to feel romantic about that mission! For years now, I have experienced those feelings whenever I conduct research. And I’ve had many of those feelings here on the 40 acres.

I find research highly personal. I form a strong emotive connection to the places it takes me. Whether I am spending a week or two in Sleepy Hollow, New York to work in the General Education Board papers, in Nashville, Tennessee to work in the Julius Rosenwald Fund papers, in Pasadena, California at the beautiful Huntington Library, or College Park, Maryland’s mammoth National Archives II facility, each place I visit leaves an imprint. For example, the panoptical monitoring in the reading room at the Rockefeller Archives with constant reminders about breaking the rules of how many pages one can access on one’s desk or how folders are filed back in their containers are as vivid to me as are the New York-style pies from The Horsman, the neighborhood pizzeria, and its views of the spectacular Hudson River. And that was two decades ago.

As a historian with my particular interests in Texas and Mexican American history, most of the sources I need, however, are in Austin and, more specifically, in the libraries here at UT. I started doing work at the Perry-Castañeda Library (PCL) in 1993-94 working on my history MA at nearby Southwest Texas State University in San Marcos (now Texas State University) where I researched the history of higher education expansion in Texas during the 1960s. In the second half of the 1990s my PhD research at Rice University on bilingual education in Texas involved exploring the university’s archival holdings, including the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, the Barker Texas History Center (now the Briscoe Center for American History), and the Benson Latin American Center. Since then I have continued to visit these archival repositories (and others in town) for biographical research on the University of Texas faculty member Dr. George I. Sánchez and for other projects.

So UT Austin has been an integral part of my professional life for decades now. What was all this time on campus like? It had a monotonous rhythm that, I’m sure, must seem tedious to anyone without a passion for history. These trips for the past three decades have entailed staying at several hotels, but most often at the I-35 Rodeway Inn near campus for a week or two at a time. This was usually during the summer months. On these trips I would get up early, scarf down a heavy breakfast knowing that I would work through lunch, and hustle across Dean Keaton Street to the Benson, Brisco, or LBJ archives to begin the day’s work as soon as they opened. I worked non-stop until closing time near 5:00 PM.

What scholars actually do in archives might seem mysterious. It’s not really. My day typically involved sifting through hundreds of pages of old documents, including old carbon copies of letters on onionskin paper. Unfortunately this work creates for me a wave of allergy-related ailments ranging from cold-like symptoms to uncomfortable skin rashes. It is a small price to pay for learning about the past as I see it. I try my best to ameliorate the expected physical response by daily prophylactic antihistamine doping, an obsessive regime of handwashing every hour or more, using gloves and masks, and a habit (learned the hard way) of not touching my face with my hands or fingers while handling documents. It may sound like odd workplace behavior, but I’ve often thought of this as equivalent to a professional athlete’s pre-game stretching and taping rituals or a singer’s voice exercises. It is necessary to get the job done. It is a built-in cost rather than a burden.

After being kicked out of the archives at closing time, I would seek an early dinner (and an urgent one due to having skipped lunch) at nearby eateries, which frequently involved the now extinct Star Seeds Café. After dinner I would walk around campus to stretch my legs. Since most of my research happened in the summer, this meant sweltering walks in athletic gear with copious amounts of sunscreen in a mostly empty University of Texas campus. These post-workday walks were solitary. I wandered campus lost in thought about what I learned that day and how it could inform the larger project.

When I was working on the Sánchez biography, I would walk past the education building bearing his name, touch the plaque, and sometimes have a few silent moments in which I reflected about the remarkable human being I was studying who taught oversubscribed courses to decades of UT students all while running his department and quietly organizing groundbreaking civil rights efforts (and suffering consequences for it) from his office in Sutton Hall. My long day of allergy-related symptoms that ended with quiet reflection on hot concrete seemed like a small lift next to Sánchez’s herculean burdens. After these walks, I placed an evening call to my girlfriend who eventually became my spouse and in time these calls also involved our growing children. They punctuated a very long day and lead to a much-needed sleep to prepare for another similarly long day. I can still remember one evening during a two-week research trip in the late 1990s having an evening cheeseburger and a Shiner Bock (or a few…) at the Star Seeds while reading a monograph on early 20th century anarcho-syndicalism along the U.S.-Mexico border by the dimmed, neon light of the bar. In that moment I was as happy as a lark, doing what I loved, though with enough self-awareness to realize I must have seemed a weird sight to the other bar patrons, who left me to my book.

However, these trips to Austin and the University of Texas contained much-needed moments in which the world outside of work joyfully broke up my owlish solitude. In the first half of the 1990s, for example, after my visits to the PCL, I would spend time with a dear cousin. We would have the kind of long chats about life that are such a part of being in one’s early 20s. In those days I also would visit a high school friend who happened to be a Longhorn football player. On one occasion this resulted in my tagging along with some very large guys to a country dance hall off of Ben White Boulevard, one of my few ventures into the famed Austin nightlife. That was fun! By the 2000s I was more personally settled. My Austin trips brought me to visit family who had moved to the area—tias, tios, and primos—at lovely dinners they provided for their vagabond relative temporarily living in a hotel near the interstate. We traded family stories and I would listen, especially to the older generations, to their lived experiences of the very things I was reading about in the archives that day.

My sense of this campus and city is, in part, also an idealized connection. As the center for intellectual and cultural life in this state, Austin always had a special meaning for me even going back to when I was an aspiring, wannabe teen intellectual living a small South Texas town. And my academic research has always felt as if it were tapping into different parts of my personal history. Going through letters written by a young Lyndon Johnson in the 1920s about teaching Mexican American children at a segregated school brought to mind my mother and her family and the stories they told me. They would have gone to the same kinds of schools from their ranches, farms, and towns in the South Texas brush country of that era; they also would have been as unknowledgeable of the English language as young Lyndon’s students in Cotulla, Texas. For my biography of George I. Sánchez, I could not but help to compare his life and choices to my own as his work gradually revealed itself to me over many years of going through his manuscript collection at the Benson Latin American Center. I even caught myself using his own rhetorical flourishes in my daily emails!

All those experiences, the jumbling of my personal and professional selves that are so firmly rooted to this university, have now evolved. In my early 50s I find myself no longer on the outside looking into an idealized UT, but on the inside looking out in a very real and now lived-in space. Being here regularly means a different kind of connection. Now I can feel the bustle of the university when the students are going to and from class (in the passing period, of course). I now teach my classes and attend meetings in the very buildings that I once only knew as exteriors from my middle-of-summer, sweaty, evening hikes. And I now notice how many things have changed since the 1990s: the campus is more walkable, but less drivable than it once was; the massive Jester parking lot has been replaced by an art museum bearing my surname (no relation); and for the first time ever I got to actually go up “The Tower” for a reception. It was a revelation after so many years staring at it from the outside wondering what it was like on the inside. I am making all-new personal connections to this place, which remains the site of so much of the intellectual odyssey that led me here. My excitement at having new colleagues and students is only enhanced by my sense of how they are deepening and expanding upon those existing memories.

The 40 acres is a special place. For me, it’s a site both familiar and unknown—one that I’m constantly rediscovering as my roads of personal and professional discovery merge in ways I couldn’t have imagined. Sadly I’ll be having these new experiences without the Star Seeds Café, but I’m sure there is plenty more to discover on the converging road ahead.

Dr. Carlos Kevin Blanton is the Barbara White Stuart Professor of Texas History at the University of Texas at Austin in the Department of History. Blanton’s books and articles involve the intersection of Chicana/o history with education, civil rights, immigration, politics, and Texas history. His George I. Sánchez: The Long Fight for Mexican American Integration (Yale University Press, 2014) won the NACCS Best Book Award; The Strange Career of Bilingual Education in Texas, 1836–1981 (Texas A&M University Press, 2004) won the TSHA’s Tulls Award; and the article “The Citizenship Sacrifice: Mexican Americans, the Saunders-Leonard Report, and the Politics of Immigration, 1951–1952” in the Western Historical Quarterly (2009) won the WHA’s Bolton-Cutter Award. He has edited A Promising Problem: The New Chicana/o History (Texas 2016) and published additional articles in professional journals such as the Journal of Southern History, the Pacific Historical Review, the Teacher’s College Record, the Journal of American Ethnic History, and Texas Monthly. Carlos holds a 1999 PhD from Rice University, a 1995 MA from Southwest Texas State University (now Texas State University in San Marcos), and a 1993 BA from Texas A&I University (now Texas A&M University-Kingsville). He has held faculty positions at Portland State University (1999-2001) and at Texas A&M University, College Station (2001-2024) before joining the University of Texas at Austin community in the fall of 2024.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.