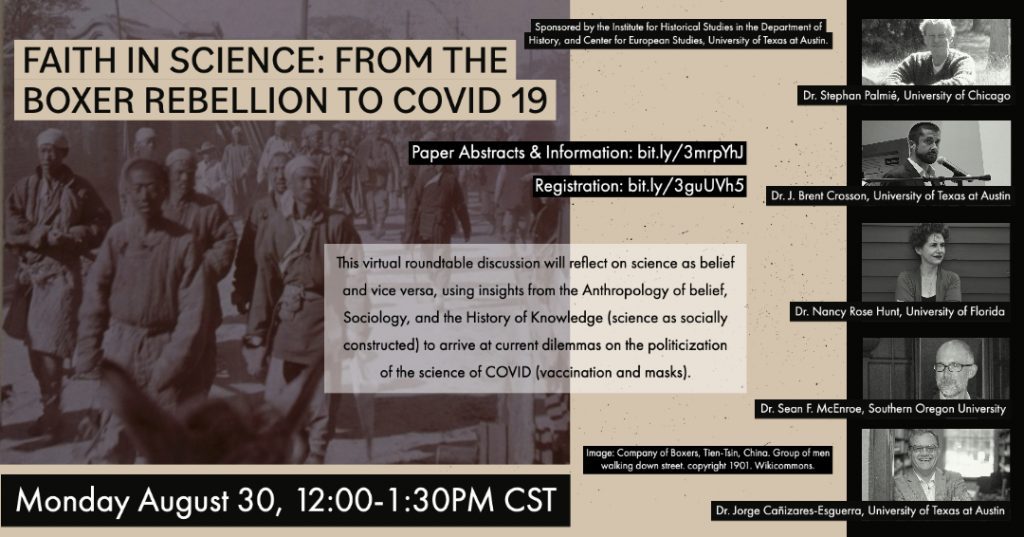

Monday August 30, 2021 • Zoom

12:00 PM – 1:30 PM

This roundtable shows the perils of dismissing as “irrational” the knowledge and beliefs of any political community, be them antivaxxers or 19th-century Fijans. Our panelists take apart the polarities that characterize lay understandings of knowledge: Science vs Religion, Science vs Magic, Belief vs. Doubt. The panelists probe the ethical and political consequences of fully embracing the insights of late 19th century Anthropologists of Belief and mid-20th-century Sociologists of Knowledge: All forms of social knowledge are deeply rational to each community. What distinguishes one form of knowledge over the other is not appeal to empiricism or skepticism. It is the power a community wields over others that transforms a system of rationality into the dominant version of reality. Often, the struggles between two or more systems of rationality within a polity are not settled through polite, civil conversation but through the use of institutional power, and sometimes armed struggles.

- “War, Magic, and Magnetism: Spiritual Weapons in the Modern World”

Paper by Dr. Sean F. McEnroe, Professor of History, Southern Oregon University, and

Visiting Research Affiliate, LLILAS Benson, University of Texas at Austin.

Abstract: The cases in this chapter (which I may eventually publish as “Immune to Bullets”) come from a narrow period of time, roughly 1890 to 1910, during a peak period of late-colonial era violence all over the word. The three cases are the Ghost Dance movement, the Boxer Rebellion, and the Maji Maji uprising. They have often been retold as tragedies in which colonized peoples, when faced with overwhelming military technology, clung to pre-modern superstitions that doomed them to defeat. The conquerors are usually remembered as rational but immoral; the victims as noble but irrational. I conclude the following: 1) That most defensive spiritual beliefs were not pre-modern or entirely traditional, but rather syncretic, improvisational, and partially informed by previous encounters with European science and technology; 2) Self-proclaimed European rationalists were at the same moment deeply engrossed in magical practices; they observed no hard boundary between science and magic, imported and exported magical ideas from the rest of the world, and routinely considered the possibility that various kinds of “primitive” magic worked; 3) Mesmerist and spiritist concepts of magnetism and invisible fluids permitted self-styled modern thinkers in Europe, the U.S., and Latin America to accept primitive magic as real, even while they maintained that it was insufficiently understood by the practitioners. This late-colonial paradigm overlaps with an earlier mentality in which Christian invaders employed unstable explanations for foreign religious practices. Foreign gods were sometimes understood as delusions and their magic as false; at other times, they were described as demons whose magic was very real, but whose practitioners misunderstood its nature. The larger book uses Mexico as a touchstone, and in this workshop piece, I may use debates over notions of magic and religion in accounts of the Spanish conquest as one bookend and the two sides of Francisco Madero (modernizer and mystic) as the other. I am exploring the materials in the Benson from the Escuela Magnético Espiritual de la Comuna Universal as part of my investigation of intellectual communities that exchanged ideas about magnetism, spiritism, and action-at-a-distance across national and linguistic boundaries.

Bio: Dr. McEnroe is a professor of history at Southern Oregon University, specializing in comparative colonial studies, religion, and state formation. He received his Ph.D. from UC Berkeley and is the author of From Colony to Nationhood in Mexico (Cambridge, 2012) and A Troubled Marriage: Indigenous Elites of the Colonial Americas (University of New Mexico, 2020). A contributor to Borderlands of the Iberian World (Oxford, 2019) and Imagining Histories of Colonial Latin America (University of New Mexico, 2017), and a past contributing editor to the Handbook of Latin American Studies and Oxford Bibliographies Online, his articles appear in Ethnohistory, The Americas, The Journal of Colonialism and Colonial Studies, and Oregon Historical Quarterly. His current book project explores the circulation of ideas about empiricism and spiritual forces among English and Spanish-speaking intellectual communities in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

- “Faith in Science”

Paper by Dr. Stephan Palmié, Norman & Edna Freehling Professor of Anthropology and of Social Sciences in the College, University of Chicago.

Abstract: Contrary to widely accepted views of science as representing unchanging, universal facts of nature in ever more accurate ways, what scientific practice actually generates are historically changing, man-made “second natures”. To the degree that our world is saturated with the objects, forces, and entities with which scientific practice populates it, we cannot but reckon with science, whether in belief or disbelief. Taking the case of present and past pandemics, and building on the insights of Arthur M. Hocart, Ludvik Fleck and Michael Polanyi, this paper argues that while faith in science – as the prodigiously productive enterprise that it surely is – may be our best bet, this does not mean that, as Polanyi (himself a trained chemist) once put it, science in itself were ultimately anything else but a “vast system of beliefs” that constantly transforms, and often does so in reaction to the transformations that the “cunning of scientific reason” wreaks upon our world.

Bio: Dr. Palmié is the Norman & Edna Freehling Professor of Anthropology and of Social Sciences in the College at the University of Chicago. He conducts ethnographic and historical research on Afro-Caribbean cultures, with an emphasis on Afro-Cuban religious formations and their relations to the history and cultures of a wider Atlantic world. His other interests include practices of historical representation and knowledge production, systems of slavery and unfree labor, constructions of race and ethnicity, conceptions of embodiment and moral personhood, and the anthropology of food and cuisine. He is the author of Das Exil der Götter: Geschichte und Vorstellungswelt einer afrokubanischen Religion (1991), Wizards and Scientists: Explorations in Afro-Cuban Modernity and Tradition (2002), and The Cooking of History: How Not to Study Afro-Cuban Religion (2013), as well as the editor of several volumes on Caribbean and Afro-Atlantic anthropology and history. He is currently completing a book entitled “Thinking with Ngangas: What Afro-Cuban Ritual Can Tell Us About Western Scientific Practice – And Vice Versa”.

- “Obeah Simplified? Scientism, Magic, and the Problem of Universals” [DRAFT]

Paper by Dr. J. Brent Crosson, Associate Professor, Department of Religious Studies; Faculty Associate, Lorenzo Long Institute for Latin American Studies; and Faculty Affiliate, Department of Anthropology, Warfield Center for African and African American Studies, and History and Philosophy of Science Program, University of Texas at Austin

Abstract: Since the late nineteenth century, countless polemics have defined science and religion through their alleged opposition. An equally problematic definition of both science and religion through their opposition to “magic” has perhaps received less attention. Encompassing a variety of divergent terms—such as witchcraft or superstition—“magic” has often been defined as false religion or false science (or, in more romantic projects of spiritualism and theosophy, as enticing alternative to organized religion or materialist science). “Obeah,” a highly stigmatized category for African-identified practices in the anglophone Caribbean, has been one such term. Like many terms associated with “magic,” obeah often played the illegitimate twin of Western science in colonial and postcolonial polemics, and “science” remains a synonym for “obeah” in Caribbean English creoles. Rather than exemplifying a unified notion of “science” either different from or similar to “magic” and “religion,” I show how this lexical equivalence reveals at least two radically different ideas of “science.” On the one hand, “Western esotericists” have often invoked a positivist, enthusiastic idea of science to uphold forms of non-Western “magic” as “scientific” alternatives to Christian religion (with obeah but one example of this). On the other hand, my Afro-Caribbean interlocutors have often used a less celebratory vision of science as an inherently dangerous and ethically fraught practice to talk about the ambivalence of power that obeah marshals to intervene in conflicts. Caribbean practitioners of African religions have thus elaborated subaltern critiques of the often-dangerous powers of science (or have harnessed those powers for forceful rituals of resistance to slavery or police violence). In contrast, religious and academic elites have used faith in an idealized science to legitimate (or, in many other contexts, denigrate) non-Western “magic.” As in contemporary controversies over COVID-19 vaccines, faith in science and skepticism about its dangers have seemingly characterized opposed approaches. However, Caribbean spiritual workers’ notions of obeah/science as dangerous do not necessarily indicate a lack of faith in science, but rather a recognition of its powers. Since increased power indicates augmented potential for harm and healing, science cannot be attached to a unitary teleology of progress or rationality, belief or doubt. Remaining within a paradigm of doubt or faith by insisting that “science” is simply true or good (or false and bad) evades responsibility for the powers of heterogeneous practices that get called “science.” In this way, projects of morally redeeming or denigrating biomedicine/science are incompatible with many Caribbean spiritual workers’ ethics of obeah/science as a dangerous practice. This article takes a closer look at this ethics of science’s powers, contrasting it with Western esotericists’ faith in science/obeah. I close by suggesting how the former ethics of power can provide resources for living in the COVID-19 pandemic’s highly politicized environment of belief/doubt with regard to “science.”

Bio: Dr. Crosson is an anthropologist of religion and secularism who works in the Caribbean and Latin America. His research has focused on contestations over the limits of legal power, science, and religion in the Americas. His first book is Experiments with Power: Obeah and the Remaking of Religion (University of Chicago Press 2020, winner of the 2021 Clifford Geertz Prize). His research on Caribbean practices of healing and legal intervention–known as obeah, spiritual work, or science–has been published in a number of journals, including Method and Theory in the Study of Religion, Ethnos, The Journal of Africana Religions, and Cosmologics. His special issue in the journal Ethnos–“What Possessed You?”–explores the relationship between spirit possession, material possessions, and conceptions of self. His work on race relations and solidarity has appeared in Anthropological Quarterly and the Duke University Press journal Small Axe. His current research focuses on climate change, religion, and conceptions of energy, with chapters on these issues forthcoming in the edited volumes Mediality on Trial (De Gruyter Press), Climate Politics and the Power of Religion (Indiana Univ. Press), and Critical Approaches to Science and Religion (Columbia Univ. Press).

Discussant

Dr. Nancy Rose Hunt has been Professor of History & African Studies at the University of Florida since 2016, after 19 years of teaching history, historiography, and within the Joint PhD Program of History and Anthropology at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. She is a medical and cultural historian of Central Africa, now working on psychiatry and madness in Bukavu, the Great Lakes Region, and beyond. Edited or co-edited volumes are forthcoming on the history of psychiatry in Africa; the Kinshasa zine artist Papa Mfumu’eto; and the a literary genius Yoka Lye. A Colonial Lexicon (Duke 1999, ASA Herskovits Prize) and A Nervous State (Duke 2016, AHA Martin Klein Prize) differently bring together religion (missions, religious movements) and science (obstetrics, gynecology/population management) and also challenge this polarity through what might be glossed as “vernacular’ forms of knowledge and “therapeutic insurgencies.” She and Achille Mbembe coordinate the Theory in Forms book series at Duke.

Moderator:

- Dr. Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra

Alice Drysdale Sheffield Professor of History

Director Institute of Historical Studies, 2021-2023

University of Texas at Austin

The event will be hosted virtually via Zoom. Please register at this link in order to receive the pre-circulated reading and link to access the event: https://utexas.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_hjJtCq3WSWWdTkplHdyQ-w.

Sponsored by: Institute for Historical Studies in the Department of History, and Center for European Studies.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.