From the editors:

Historical scholarship is underpinned by rigorous investigation of sources and archives. But historians can also leverage their knowledge of the past to think critically about the present. Jeremi Suri, the Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, exemplifies this practice. In October, Dr. Suri published his fifth book, entitled Civil War by Other Means: America’s Long and Unfinished Fight for Democracy. As its title suggests, the book reinterprets the history of the American Civil War in order to shed new light on the ongoing struggle for racial justice in the United States.

To mark the publication of Civil War by Other Means, Not Even Past invited three scholars of American history, each with unique expertise, to review the book. Their reviews are published below.

As a teaching assistant for a United States history course at the University of Texas at Austin, I would ask my students a simple question: who won the Civil War? The students, after sharing confused glances with each other, would often respond with “The North?” or “The Union?” I assured them that it wasn’t a trick question before describing the history of our campus. In 2015, the university moved a statue of Confederate President Jefferson Davis from the South Mall to the Briscoe Center for American History, a museum and archive also located on campus. The Davis statue was commissioned by university benefactor George Littlefield and dedicated in 1933 – almost seventy-years after the Civil War ended. In 2017, during my first week of graduate school, the university removed four more statues commemorating Confederate figures and took down the Confederate flags throughout the campus. The students were of course correct that the Union defeated the Confederates on the battlefield, but as the physical landscape of campus suggests, many of the Southern symbols and ideals lived on. Students walked past these Confederate monuments each day, yet they did not fully grasp how the campus connected past and present.

After reading Jeremi Suri’s Civil War by Other Means, I’m considering another question: when did the Civil War end? According to Suri, the Civil War has continued into the twenty-first century. Through political posturing, racial terror, and disenfranchisement, Suri argues that the late 1860s and ‘70s did not represent “a culmination but a continuation” of the Civil War. In the January 6th Riot and the Insurrection at the Capitol Building in Washington, D. C., the same ideas that motivated Confederate leaders to secede from the Union also pushed white nationalists to storm the halls of Congress and physically intimidate elected officials. Rioters invoked the memory of the Confederacy through symbols, including the Confederate flag and a noose – two images with deep connections to white supremacy. In Civil War By Other Means, Suri’s adept interpretation of the explicit and subtle forms of division after the military struggle between the Union and Confederacy offers valuable perspectives in how we view the conflict today.

Suri’s book blends popular narratives with often overlooked events to illustrate the depths of the political and ideological battle that took place before, during, and after the Civil War. While standard understandings of the conflict establish a clear ending with Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Ulysses Grant in April 1865, Suri takes an alternative approach by examining the continued efforts to maintain a “Southern way of life.” For example, it is well-known that Andrew Johnson’s preferential treatment of secessionists played a role in his impeachment in 1868. Yet, many people are unaware of the Confederates that traveled further south into Mexico and formed an alliance with Mexican Emperor Maximilian I in an attempt to develop a Confederate colony near the U.S.-Mexico border. Former Confederate supporters and politicians held fast to notions of forced servitude, developed memorials and symbols to honor soldiers, produced conditions that led to the formation of the Ku Klux Klan, and reinforced white supremacy in the two decades following the military conflict. There is ample evidence not of the end, but the extension of the Civil War.

Suri’s Civil War by Other Means deftly captures the evolution of historical interpretation. As our collective memory of the Civil War changes, the views of the people dedicated to remembering the conflict – for better or worse – evolve as well. This is particularly important in the current political climate. In addition to the Insurrection at the Capitol, racial justice protests demanded the removal of Confederate memorials. In many cases, protestors refused to wait for public officials to take action and, instead, engaged in the destruction or removal of monuments themselves. As Suri argues, this is integral to the contemporary culture wars that can be traced back to the decades following the Civil War and how policies, practices, and ideas shaped the “Lost Cause” of the Confederacy. Since then, an ideological struggle has taken shape in classrooms, courtrooms, and the general public based on interpretations of the Civil War.

Americans’ collective memory of the Civil War, as evidenced through the January 6th Riot, continues to influence contemporary society, politics, and culture. Suri’s important study of the two decades following the military conflict is necessary for how we teach and remember the Civil War – not only in the South, but beyond the former Confederacy. Now that I’m teaching outside of the South for the first time, I’m aware that historical memory of the Civil War is not only dependent on what we learn in the classroom, but what we also see in our daily lives. Although I haven’t encountered Confederate symbols where I currently live and work in Utah, there are remnants of the white supremacist ideologies that motivated secession in 1861 and resonates with groups of people in the American West – an area of the U.S. with a problematic racial history itself.

Suri’s engaging and accessible writing style makes Civil War by Other Means a critical addition to the growing body of scholarship on historical events and collective memory. This book stands out for its simple but thought-provoking questions, which forces readers to wrestle with the meaning of history and how it shapes our day-to-day lives. Whether in the classroom or around the kitchen table, Suri’s Civil War by Other Means will spark hard conversations about history, memory, and citizenship.

Brandon James Render is an assistant professor of history at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. His current book project, Colorblind University: A History of Racial Inequity in Higher Education, explores the intellectual genealogy of racial colorblindness throughout the twentieth century

Two sequential survey courses covering the full arc of US history undergird historical education at nearly every university in the country. Programs disagree, however, about which year should divide the two courses. Many schools draw the line at 1865, highlighting the surrender of Confederate forces and the end of open hostilities in the Civil War. Others split their courses in 1877, using the ostensible end of Reconstruction as a bookend. Jeremi Suri’s Civil War by Other Means shows why delineating between the two “halves” of American history is so difficult no matter where the cut is made. Suri dispels the notion that the Civil War ended with Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. He instead explains how the war moved from “muddy battlefields to the marble halls of Congress, various statehouses, a theater, and a train station.”[1] The war’s transmutation underscores the challenge of periodizing this juncture in American history.

The book’s title is a subtle nod to the German military theorist Carl von Clausewitz, who famously asserted that “war is the continuation of politics by other means.” Suri’s argument inverts this observation to elucidate how political struggles, from 1865 onward, constituted a continuation of war by other means. In depicting these various means, Suri traces the lionization of John Wilkes Booth, follows former Confederates to the failed colony of Carlota, illustrates the intrigues of Andrew Johnson’s impeachment, and recounts the withdrawal of federal troops from their postbellum occupation of the American South – effectively ending Radical Republicans‘ efforts to establish a multiracial democracy. As with so many good histories, the strength of this narrative comes from the striking characters whom Suri profiles. Figures ranging from Matthew Fontaine Maury, a celebrity scientist and ardent defender of white supremacy, to Henry Adams, an indefatigable Black community organizer, to Charles Guiteau, the poster child of fragile masculinity, populate an absorbing account of the battle between exclusive and inclusive visions of democracy.

Suri centers his first five chapters on key groups who emerged from Civil War battlefields with unfinished business. The first two chapters contrast the martyrdom of President Abraham Lincoln and Booth, his assassin. The commemoration of both serviced a renewed “mobilization” of men and women on the opposing sides of the unresolved conflict.[2] The next chapter follows Confederate exiles, who refused to accept defeat and migrated to Mexico with ambitions to regroup and relaunch the “Lost Cause.” Meanwhile, newly emancipated African Americans sought to secure the rights and opportunities promised them by the reconstruction amendments. In this postwar period, fissures within the Republican Party emerged as Southern resistance tested the resolve of Lincoln’s party to realize his vision of a multiracial democracy.

The final five chapters detail several of the new battles of the enduring Civil War. The first presidential impeachment pitted Republicans against the defiant accidental president Andrew Johnson. Former Confederate states witnessed recurring outbursts of vigilantism that occupying Union forces struggled to curb. The next battle took the form of the contested election of 1876, finally “resolved” through the withdrawal of federal troops from the South and the election of a “caretaker” executive in Rutherford B. Hayes. Finally, the assassination of James Garfield marked a defeat for Republicans that left African Americans more “repressed than at any time since Appomattox.”[3]

Civil War by Other Means demonstrates how contemporary experiences can generate fruitful new examinations of moments already richly chronicled by earlier generations of historians. While this account does not tread much new scholarly ground or unearth unexamined sources, it eloquently provides a succinct framework for thinking about the long-standing struggle for democracy and inclusivity. Events of the past several years have laid bare how incomplete this struggle remains today. It’s a dismaying state of affairs, but it also underscores the value of reexamining our past to help inform efforts toward improving our democratic society. To this end, Suri’s closing chapter addresses “our troubles today,” identifying historical lessons and proposing ways to pull up the “intricate roots” of racism and white supremacy.[4] These ideas define Suri’s scholarly activism, which he cites as an inspiration for his book. They also strike a much-needed optimistic note to close an often dispiriting description of the United States’ democratic deficiencies.

Suri has crafted a book with appeal for a broad audience. It can simultaneously speak to young adults seeking to understand the historical origins of the United States’ ongoing dialogue on race as well as scholars looking for a concise account that explains how debates about race infused U. S. politics during the era of Reconstruction and beyond. Regardless of the perspective from which readers approach Civil War by Other Means, we can only hope they heed its call to take up the task of building a better democracy. As Suri closes this excellent book, there’s “lots of good work to do.”

Jon Buchleiter is a graduate student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. He studies the institutionalization of nuclear arms control and disarmament efforts as an important element of US foreign policy during the Cold War. At UT, Jon is a graduate fellow with the Clements Center for National Security.

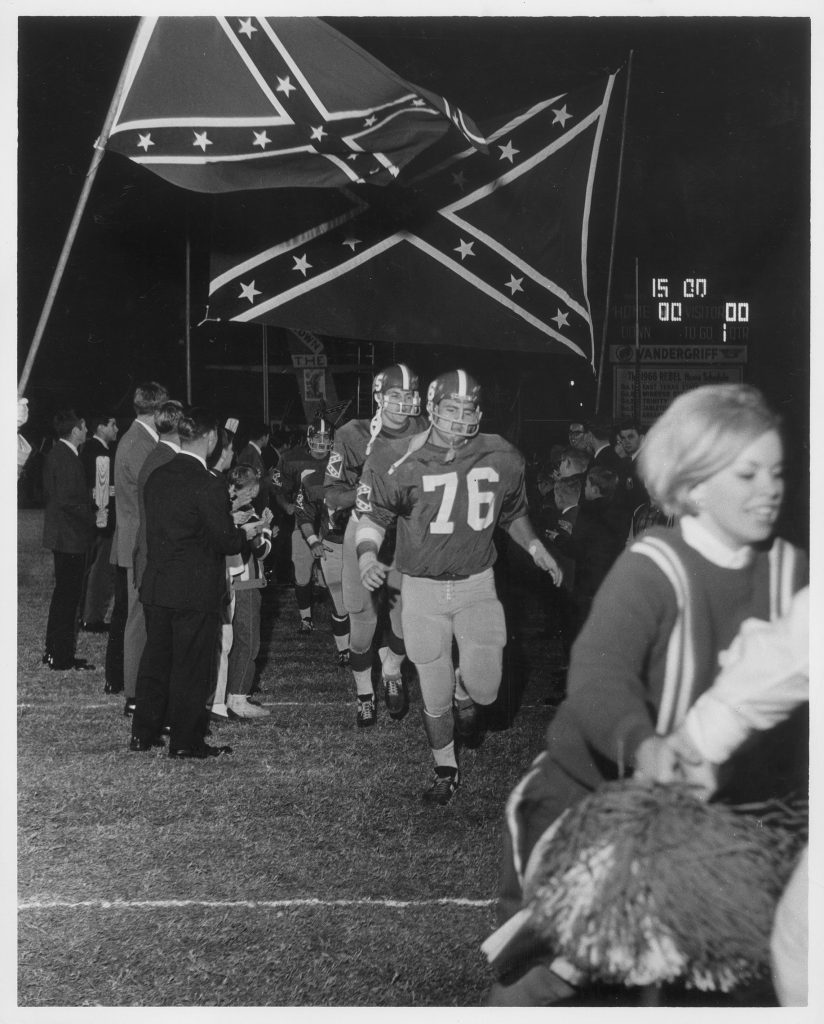

During the 1950s and 1960s, following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board, white Southerners opposing school integration used Confederate symbols, alongside violence and intimidation directed toward Black students, to express their defiance. In 1957, for instance, the local school board in Tyler, Texas, decided to rename the city’s new, all-white high school after Robert E. Lee. Students adopted “the Rebels” as their mascot, and they proudly displayed the Confederate flag at school events. In Tyler and elsewhere, young people born generations after the Civil War resurrected these images as a way to articulate their own politics. According to Jeremi Suri, these incidents were not merely efforts to cling to the past but actually represented a continuation of the war in the American political imagination.

In Civil War by Other Means, Suri examines the tumultuous decades immediately following the Civil War. Unsettled debates over democracy and citizenship resurfaced with renewed strength during this period, and they “created a pattern for exclusion, violence, and coup plotting that repeated in the twenty-first century.”[5] The political compromises that Republicans and Democrats brokered between 1865 and 1885 left many of the war’s underlying issues unresolved. Most notably, Republicans’ desires for moderation and national reconciliation encouraged politicians, from Andrew Johnson to Rutherford Hayes, to exercise leniency toward the white South at the expense of freedpeople. Drawing from a large body of secondary literature, along with presidential papers, congressional records, and periodicals, Suri demonstrates how these “lingering embers” have erupted at key moments in U.S. history.

Perhaps one of the most powerful examples that Suri uses is the literal continuation of the war by Confederate generals who refused to admit defeat. Following the official surrender at Appomattox, groups of Confederate soldiers traveled south into Mexico in hopes of recreating a Southern planter aristocracy. Upon returning to the United States, these “exiles” did not abandon their visions for society. Instead, they worked to reinscribe racial hierarchies as architects of the New South. They served as state legislators, funded Confederate monuments, joined historical associations, and accumulated wealth through various business ventures. Alexander Watkins Terrell offers one example. After returning to Texas, Terrell became a state legislator and authored a slate of restrictive voting bills passed during the early twentieth century. Designed to disenfranchise Black voters, these bills established the state’s direct primary system, extended poll tax requirements to primary elections, and permitted political parties to prescribe qualifications for voters. Terrell’s biography supports Suri’s conclusion: “The men who fled the American South after Appomattox were also the men who made the American nation in the next decades. They converted the treachery of their exile into a narrative of courage, loyalty, and commitment.”[6]

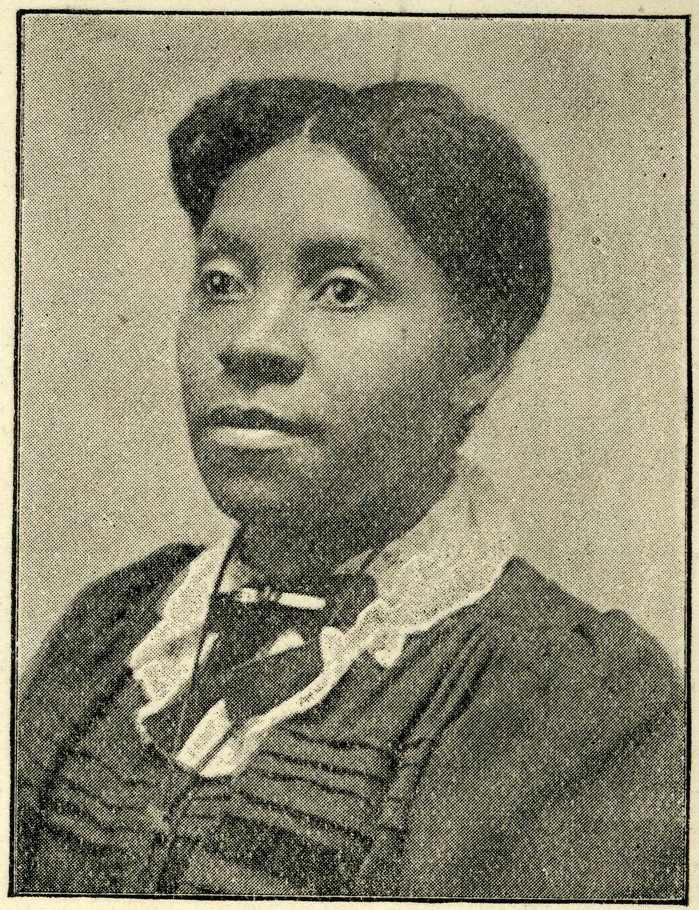

While Terrell and his colleagues worked to undermine federal civil rights legislation and restrict voting rights, Black Americans consistently pushed for more expansive visions of citizenship as voters, soldiers, and elected officials. Debates about American democracy did not only take place in the national capital and state legislatures, however. They also materialized at the local level, in the churches, schoolhouses, and other community institutions that formerly enslaved people built following emancipation. While Suri explores how Black men redefined citizenship through military service and political participation, his emphasis on formal politics sometimes obscures Black women’s contributions. In addition to serving as nurses, educators, and caretakers, Black women who lacked access to traditional political channels sought other ways to assert their visions for society. They played active roles in advocating for individual and collective restitution. For instance, in 1870, Henrietta Wood filed a suit against her former enslaver in a federal court and, after a decade of litigation, won her case. Later, during the 1890s, Callie House mobilized people across the South through the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty, and Pension Association. House and her colleagues lobbied for pensions for ex-slaves and eventually filed suit against the federal government, inspiring many subsequent efforts for reparation. Including these often-overlooked struggles in the narrative would strengthen Suri’s argument and expand our understanding of how these conflicts played out on multiple levels.

Suri does many things well in this book. His conceptualization of ongoing debates about American democracy as a continuation of the Civil War “by other means” is compelling, and it offers a useful framework for people interested in exploring contemporary U.S. politics through an historical lens. Suri’s engaging writing style also makes the book appealing to a wide audience. He manages to make complex political history not only accessible but actually enjoyable to read. Finally, this book provides a timely and important critique of several key features of the U.S. political system. In Suri’s words, Southern resistance “thrived [because] it had many advantages in the American democratic system.”[7] By identifying some of these features—including the structure of the electoral college, election certification procedures, and longstanding efforts to restrict voting rights—Suri challenges his reader to think critically about the future of American democracy.

Sarah Porter is a graduate student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. She studies twentieth century social movements, policing, and mass incarceration in the United States.

[1] Jeremi Suri, Civil War by Other Means: America’s Long and Unfinished Fight for Democracy (New York: Public Affairs, 2022), 261.

[2] ibid., 27.

[3] ibid., 256.

[4] ibid., 270.

[5] ibid., 9.

[6] ibid., 65.

[7] ibid., 259.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.