From the editors:

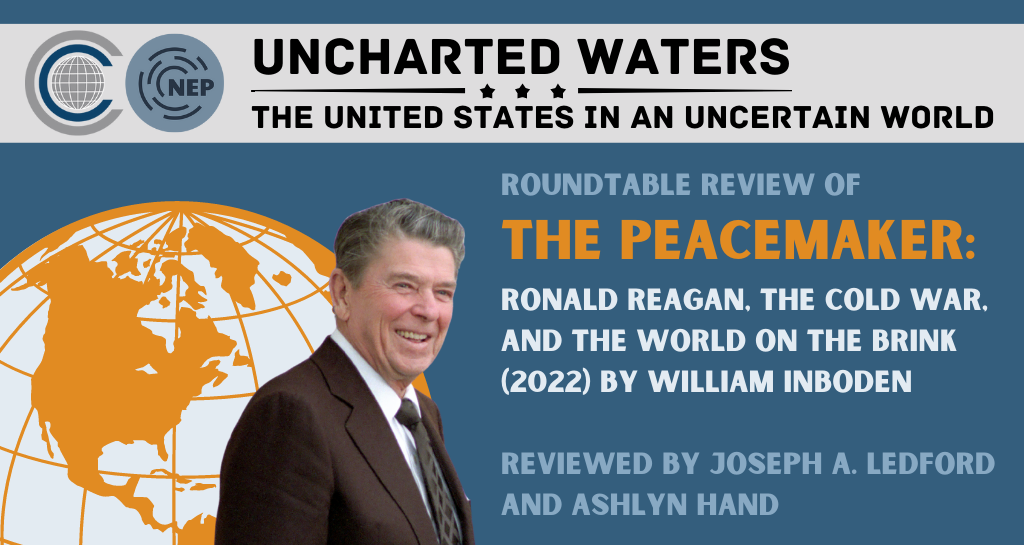

William Inboden is the William J. Power, Jr. executive director of the Clements Center for National Security at the University of Texas at Austin. A former State Department official who served on the National Security Council under President George W. Bush, Inboden is also a distinguished scholar of international history. His most recent book, entitled The Peacemaker: Ronald Reagan, the Cold War, and the World on the Brink, presents a definitive account of the Reagan administration’s foreign policy achievements.

To mark The Peacemaker‘s publication, Not Even Past invited historians Joseph A. Ledford and Ashlyn Hand to review its contents. Ledford and Hand are rising stars in the world of historical scholarship. Their reviews deftly describe Inboden’s key insights, showing how Reagan strove to bring peace and order to the deeply unsettled world of the 1980s. Few presidents have grappled with greater international uncertainty. But as Inboden’s book demonstrates, Reagan was able to build a lasting legacy through his skillful navigation of the late Cold War’s uncharted waters.

Speaking to a private scholarly gathering at the Library of Congress in 1986, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger remarked that, “when you meet the President, you ask yourself, ‘How did it ever occur to anybody that he should be Governor, much less President?’” Still, Kissinger confessed of President Ronald Reagan: “He has a kind of instinct that I cannot explain.” In The Peacemaker, William Inboden not only provides clarity on Reagan’s instinct, but also furnishes the preeminent account of his statecraft, from the origins of Reagan’s 1980 presidential campaign to his December 4th, 1992, address to the Oxford Union, replete with insightful anecdotes and perceptive analysis.

A cavalcade of declassification over the past decade has helped Inboden offer greater insight into Reagan’s policymaking. To explain Reagan’s statecraft, Inboden identifies in Reagan’s foreign policy seven themes that derive from both the archives and his worldview: allies and partners; history; force and diplomacy; religious faith and religious freedom; tragedy; battle of ideas; and expansion of liberty. These seven themes reflect a hawkish but nuclear abolitionist Reagan deeply engaged in crafting and executing his foreign policy—a president determined to harness American power and allied support to challenge the Soviet Union and secure peace. The dynamic nature of liberal democracy and market capitalism, Reagan fervently believed, advantaged the United States, and sustained his diplomatic and military campaign against the Soviets. Reagan sought not only diplomacy underpinned by a mighty American military buildup, but also the spread of political and religious freedoms to uplift the oppressed and undermine authoritarians.

Inboden’s seven themes weave through an engrossing narrative, which also serves an important methodological purpose. Foreign-policy decisions are neither made in an isolated context nor arrived at with absolute certainty. Drawing on his policymaking experience and historical craft, Inboden successfully captures in narrative form the precariousness of policymaking as the Reagan administration lived it. In doing so, Inboden eloquently reconstructs the messy reality of the international affairs in which Reagan dealt.

At once judicious and bold, The Peacemaker presents three interrelated arguments about Reagan’s bid to master 1980s geopolitics. First, alongside Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Reagan had the most significant modern presidency. In January 1981, Reagan confronted the Soviet Union at the zenith of its military power during the Cold War—a fearsome Soviet Union that had invaded Afghanistan, aided revolution across the globe, and tightened its grip behind the Iron Curtain. An onslaught of other geopolitical threats faced the president, too. In Africa, apartheid persisted, and the last vestiges of colonialism precipitated civil war. Latin America was awash in blood from the Cold War’s destructive forces. The Iranian Revolution destabilized the Middle East, and the rise of terrorism confounded policymakers. These grave issues posed vexing challenges, in addition to the problems besetting Western Europe and Asia. Inside America, Reagan grappled with a crisis of confidence and institutions, a consequence of 1970s domestic tumult and economic downturn.

As Inboden shows, however, the Reagan Revolution cast the foundations of a new world order out of the deadly frost of the Cold War. By January 1989, the United States appeared rejuvenated economically, politically, and militarily. A wave of democracy flowed from Argentina, Chile, El Salvador to South Korea, the Philippines, and Taiwan. The “evil empire” slouched toward the ash heap of history. Reagan achieved arms reduction with the Soviet Union and, in turn, lessened the chances of nuclear annihilation. “The Iron Curtin and Berlin Wall may have appeared to the naked eye to still be standing,” Inboden observes, “but the forces that would bring them down were already boring away within” (476). The Cold War ended in short order. With the added benefit of structural forces moving to its advantage, the United States reached unipolarity under the leadership of Reagan’s successor and vice president, George H. W. Bush.

Second, and stemming from the first argument, Reagan’s grand strategy for waging the Cold War brought the Soviet Union to a “negotiated surrender,” one in which Reagan pursued diplomacy to curb hostilities and reduce the nuclear threat while marshalling all the resources of the United States to extirpate Soviet communism from the earth. Paul Nitze’s walk in the Geneva woods initiated a sprint toward arms reductions, culminating in Reagan signing the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. During this arms race to zero, as Inboden details, Reagan embarked on the Strategic Defense Initiative, a missile defense system that scientist Edward Teller encouraged, and a cross-section of experts ridiculed, but the Soviets feared. Reagan upgraded the US armed forces, building unrivaled weaponry using new technologies. He unified the Western alliance against the Soviet Union, Warsaw Pact satellites, and other Soviet-supported authoritarians. And, crucially, he brought the Reagan Doctrine to bear on Soviet advancement in the Global South while inspiring dissidents under the yoke of communism with stirring rhetoric and covert assistance.

Third, and responsible for the second argument, Reagan effected a Cold War grand strategy through economic restoration, defense modernization, political and religious liberty promotion, nuclear weapons abolition, anticommunist insurgency financing, and the obsolescence of mutual assured destruction, a set of actions codified by National Security Decision Directives 12, 13, 32, 54, 71, 75, 166, 238, and 302. Here, Inboden daringly—and ultimately persuasively—argues that these prongs of Reagan’s strategy combined to stress the Soviet system and create the conditions that influenced the ascendence of Mikhail Gorbachev, a reformer who embraced Reagan’s diplomatic overtures to mitigate the deleterious effects of American power.

From this vantage, Reagan’s record may seem unblemished. Yet, despite rendering an overall positive judgement, Inboden does not pull punches on Reagan’s mistakes. In the Global South, Reagan’s policies could be counterproductive and tragic. In Lebanon, for instance, Inboden sharply criticizes Reagan’s handling of the Marine barracks bombing, particularly the president’s decision to not retaliate. “His failure to do so,” Inboden judges, “damaged American credibility, hurt relations with an important ally [France], and invited further terrorist attacks” (256). In Nicaragua, Reagan’s harbor mining operation proved a self-inflicted political disaster. “The mines,” Inboden contends, “did far more damage to America’s global reputation than to the Sandinista economy” (286). So, too, did Reagan’s support for disreputable anticommunist leaders and insurgents compromise his administration’s moral standing.

Inside the White House, meanwhile, Reagan often expressed indifference to perennial squabbling among staff and avoided personal confrontations. His inattention to the minutiae of being president manifested infamously in the Iran-Contra affair, a harebrained scheme involving arms-for-hostages deals with Iran and the diversion of the profits to the Contras in violation of the Boland amendments. Reagan arguably made his greatest blunder with Iran-Contra. As Inboden puts it: Iran-Contra “violated several of his own strategic principles, such as: Negotiate from strength. Keep faith with allies. Incentivize adversaries to engage in good behavior; do not reward bad behavior. Build public support for policies rather than keeping them secret. Even ‘trust but verify’” (423).

By contrasting Iran-Contra with the Geneva Summit, however, Inboden encapsulates the enigmatic Reagan in a single passage. During Iran-Contra, Inboden notes, Reagan exhibited his legendary stubbornness, disregarded sage advice from trusted cabinet members, and deluded himself into thinking that arms-for-hostages was not his cardinal objective. The scandal could have been easily avoided if Reagan had not followed his worst instincts. At Geneva, conversely, Reagan confidently pursued his creative strategy for ending the Cold War across ten sessions with Gorbachev, laying the groundwork for the conflict’s resolution. He formed a true relationship with Gorbachev while pressuring him on arms reductions and human rights. Reagan was in his element. His courage and convictions both impressed and distressed the Soviet leader.

Although Reagan could not quote Thomas Schelling chapter and verse, he abhorred nuclear weapons, committed to a singular vision about world order, and possessed an uncanny ability to cut to the heart of policy matters. In a revealing anecdote, Inboden recounts Reagan’s visit to the North American Air Defense Command in 1979, during which General James Hill informed him that America did not maintain a defense against nuclear weapons, only the facility to counterattack. Reagan concluded that relying on mutually assured destruction was no way to live. This grim realization reinforced Reagan’s belief in nuclear abolition and his resolve to peacefully end the Cold War. As Inboden lucidly demonstrates, Reagan articulated the genesis of his plan in the 1970s, established the means during his first term, and delivered on the ends in his second term.

Inboden’s vivid portrayal of Reagan refutes the reversal thesis that he somehow transformed during his second term. The Cold War changed, not Reagan. The 40th president called for the zero option in 1981 and made good on his promise in 1987 by seeking “peace through strength.” (65) Only one version of Reagan served as president, and he comes alive in The Peacemaker.

Joseph A. Ledford is an America in the World Consortium Postdoctoral Fellow at the Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

In The Peacemaker: Ronald Reagan, the Cold War, & the World on the Brink, William Inboden offers the first comprehensive analysis of Ronald Reagan’s foreign policy. It is a brilliantly written narrative of complicated characters and strategic vision during the final decade of the Cold War. The Cold War was not a foregone conclusion, and Inboden’s book evokes the peril and urgency of the time. The sobering reality of a potential hot war—one with the capability of obliterating humankind–sits in the narrative like a member of Reagan’s inner circle and demands intellectual empathy from the reader.

Inboden argues that Reagan understood the Cold War fundamentally as a battle of ideas made more complex because of great power competition. This contrasted with the more common understanding of the Cold War as a classic great power competition with an ideological element. This difference in framing meant that Reagan saw Soviet communism as an enemy to be defeated rather than party to a conflict to be managed or contained.

But how to defeat communism without launching World War III? Inboden describes Reagan’s goal as “negotiated surrender,” in which Reagan applied sufficient pressure and exploited Soviet vulnerabilities to puncture the Soviet system while extending a hand in diplomatic outreach. Inboden recognizes that these goals were, at times, in contradiction. Still, he maintains that Reagan himself “held tenaciously to both” (4).

One central theme in The Peacemaker is Reagan’s commitment to religious freedom and the expansion of liberty. Vis-à-vis the Soviet Union, Reagan pushed for the protection of Jewish refuseniks and persecuted religious believers like the Siberian Seven, a group of Pentecostals who sought refuge in the American Embassy in Moscow in 1978. But as Inboden addresses, Reagan’s Cold War lens could prevent him from acknowledging the brutality of regimes in places like El Salvador and Argentina (106).

Inboden also highlights the role of historical memory in shaping foreign policy decision-making. Whether it be Bill Casey’s likening Soviet communism to Nazism or the ever-present fear of another Vietnam, the centrality of history is a recurring theme.

The book unfolds chronologically, giving the reader a taste of the sheer volume of strategic challenges facing the Oval Office–a reality Secretary of State George Shultz called the “simultaneity of events” (7). The number of issues vying for presidential attention at any one moment is overwhelming, a situation sometimes made more stressful by the eclectic cast of characters in Reagan’s cabinet. Relying on newly released documents and meticulous archival research, Inboden captures the idiosyncrasies, missteps, and glories of the Reagan team.

In the end, the Cold War outlasted Reagan’s time in office. Still, Inboden maintains, “Reagan had transformed the art of the possible. Things inconceivable in 1980 became reality by 1989” (475). The Peacemaker is key reading material to better understand foreign policy challenges of the Cold War and the strategic vision of the 40th president.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.