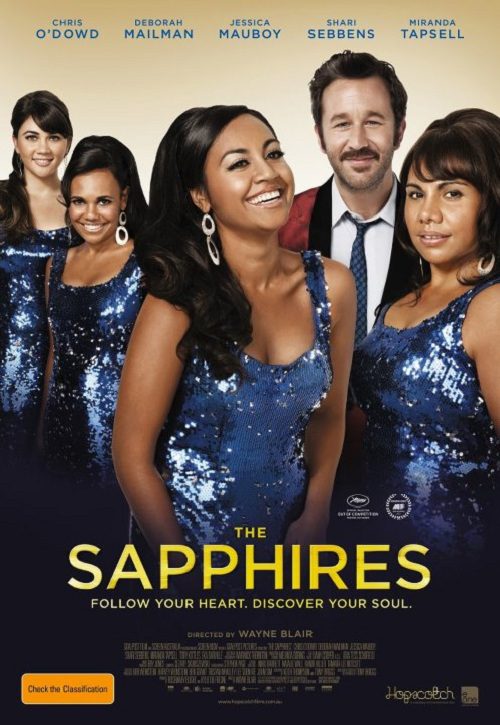

Wayne Blair’s The Sapphires is the best new historical film that you most likely have not seen, yet. It is based on Tony Briggs’ 2004 play with the same name and premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2012. It tells the story of four Aboriginal women singers from the Cummeragunja Mission in rural New South Wales, Australia, who travelled as “The Sapphires” to Vietnam in 1968 to entertain US troops there. The film is based on a true story that Blair knows intimately: his mother, Laurel Robinson, and her sister, Lois Peeler, were members of the band.

Music is the highlight of the film. Deborah Mailman, Jessica Mauboy, Shari Sebbens, and Miranda Tapsell have amazing voices and create beautiful harmonies. It is a pleasure to watch The Sapphires wearing brilliant costumes and performing covers of American soul hits from the late 1960s including “What a Man” and “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” in front of rowdy soldiers in darkly-lit Saigon bars and rural military camps. Off stage we hear The Sapphires sing the gospel song “Ngarra Burra Ferra” in Yorta Yorta, the native tongue of the original band-members.

In Australia, critics have welcomed the film as a feel-good story about Indigenous people that offers relief from the harsh themes of poverty, violence and drug and alcohol abuse that have been prominent in other recent films about Aboriginal communities, such as Samson and Delilah.

This does not mean that the Blair has ignored issues that still shape the lives of Aboriginals and make many Australians uncomfortable. Racism is an important theme in The Sapphires. We are introduced to the band at talent quest in a country pub – a place where Aboriginal patrons are not welcomed. We watch white audience members leave rather than listen to the sisters sing. The film also explores how the war-torn Vietnam of the 1960s was a place that Aboriginal people – in this case the members of a band – interacted with African Americans for the first time in their lives, and suggests that such encounters initiated the formation of transnational conceptions of black identity.

Members of the Royal Australian Air Force arrive at Tan Son Nhut Airport, Saigon, August 10, 1964 (Image courtesy of the U.S. Government)

The problems of “the stolen generation” are also addressed. Approximately 100,000 indigenous children in Australia were removed from their families and sent to be raised in white families before the 1960s. One member of the band, Kay, is criticised for ostensibly abandoning her Aboriginal identity and living as a white woman, which is facilitated by her light skin tone. It is eventually revealed that the government forcibly removed Kay from her family as a child and placed her with a white family in a city far away from home. Kay struggles make sense of her indigeneity after a long separation from her family members. The Sapphires’ experience in Vietnam was perhaps unique, but the wounds created by forced removal of children are still felt by many people.

The four Aboriginal singers–sisters Laurel Robinson, Lois Peeler and their cousins Beverley Briggs and Naomi Mayers–who inspired the film (Image courtesy of Hopscotch Films)

It would be unfair to say that The Sapphires romanticizes war, but it is disappointing that the film makes no attempt to delve into the complex politics surrounding the Vietnam War in Australia. Certainly the film addresses the dangers that entertainers confronted in a war zone – for example, on one occasion the camp where the band is performing is bombed. But the version of The Sapphires’ story told on the big screen conveniently erases opposition to the Vietnam War that manifested in a vibrant culture of protest. Back in 1968, two original members of the band, Naomi and Beverly, refused to join the Vietnam tour because they were staunchly opposed to the conflict and US imperialism in South-East Asia. They had participated in Melbourne’s large moratorium movement, and could not bring themselves to entertain soldiers fighting a war they understood as fundamentally immoral. This is a glaring hole in the story that should not have been excluded. Films about our past are as valuable for what they exclude as for what they include.