Good afternoon, everyone! Thanks so much for joining us. Today, I will be offering a short meditation on cultural memory and the Vietnam War using two case studies that first appeared as blockbuster novels published during the war, and then adapted into popular films, which premiered after the war had ended. While the novels vividly articulated a fractious and divided national zeitgeist during the war, the films transformed the cultural memory of the war through plot twists of revisionism and historical erasure. The first case study, First Blood, is readily familiar as a Vietnam story; the second, Jaws, is less so.

In August 1968, a twenty-five year old graduate student named David Morrell had a creative epiphany while watching the CBS Evening News. The first story was at the scene of a chaotic firefight in the heavily foliated outskirts of Saigon. American soldiers fired from M-16s in response to an enemy assault. The second story—as Morrell recalled it—was about urban unrest in America. Images of smoke, burning buildings, broken glass, and National Guardsmen marching with M-16s filled his small TV screen. (Given the vagaries of memory, Morrell might have actually been watching a report about the antiwar protests at the Democratic National Convention on August 26-29, rather than the urban rebellions, which occurred in the aftermath of Martin Luther King’s assassination on April 4, 1968.): “It occurred to me that, if I’d turned off the sound…I might have thought that both film clips were two aspects of one horror…. The juxtaposition made me decide to write a novel in which the Vietnam War literally came home to America.”[i]

Morrell’s protagonists were both veterans and both told their own story from different generational perspectives. The first was a longhaired Vietnam veteran named Rambo, a Green Beret who had won the Congressional Medal of Honor, but suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), adrift, alone, and unemployed in a softening American economy. The second was a Korean War veteran and winner of the Distinguished Service Cross named Wilfred Teasle, a police chief in Madison, Kentucky. Rambo walks into Madison looking for something to eat, where Teasle immediately picks him up and drops him off outside the city limits. Tired of being treated as a social outcast, Rambo decides to stand his ground and return to the town—twice. Finally he is arrested, brutalized in the town jail, escapes, amasses a small arsenal, and returns to war as he lays siege in the woods and kills countless people. His commanding Special Forces officer in Vietnam, Sam Trautman, is called to mediate the standoff, which ends badly: Rambo shoots and kills Teasle and Trautman kills Rambo. Published in 1972, First Blood was translated into twenty-one languages and Morrell immediately sold the film rights to Columbia Pictures.

But the film languished for ten years.[ii] Morrell’s sympathetic portrayal of Rambo and Teasle as complex and flawed human beings did not readily translate into visual form. Finally, after its new directors made substantial changes to the plot, the film was released in 1982. Rambo was given a first name—Johnny, as in “When Johnny Comes Marching Home.” His movement through the small town—set here in the Pacific Northwest—is now purposeful: in the opening scene, Rambo is trying to find a fellow soldier, Delmar Berry, whose family sorrowfully informs him that Delmar is dead. Teasle is now a flat, purely reactionary character. While still volatile, Rambo rarely kills. Rambo merely wounds Teasle. Most significantly, Rambo lives, which allowed for the possibility of serialization.[iii] In the film’s final moments, Rambo surrenders to Trautman, but indicts the society that failed him, “And I had to do what I had to do to win. But somebody wouldn’t let us win.”[iv]

The theme of the abandoned soldier is blasted writ large in the film’s first sequel, Rambo (First Blood Part II): Rambo is released from prison to return to Vietnam on a special mission to search for American POWs. Released in 1985, the film was an international box office hit—the first of three sequels, which Morrell likened to “westerns or Tarzan films.” First Blood Part II’s celebration of Rambo’s massively muscled heroics and its erasure of ambivalence about the nation’s involvement in Vietnam gave popular form to President Reagan’s full-throated declarations of whipping the “Vietnam Syndrome.”

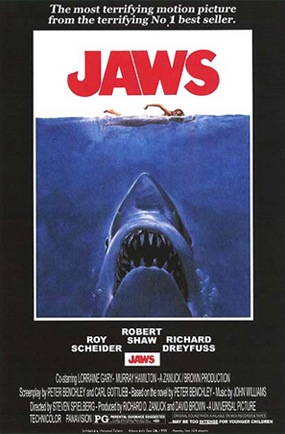

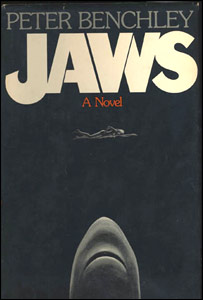

At the time of First Blood’s publication in 1972, a writer named Peter Benchley was drafting an “Untitled Novel” about the social and economic chaos unleashed by a murderous great white shark that eats five people at a beach community on Long Island. A member of the celebrated Benchley literary family, Peter grew up watching marine life at his family’s summer home in Nantucket. His childhood fascination with sharks endured at Harvard and his subsequent career as a journalist and a speechwriter in the Johnson Administration. Benchley’s privileged background gave him an intimate sense of the WASPY summer people who populate his fictional seaside community of Amity in the novel that he finally named Jaws.[v] References to Vietnam punctuate the novel. In an early draft, Benchley describes the young adult summer people, the lifeblood of this struggling seaside community, as virtually immune to the shocks of war and socioeconomic upheaval because of their wealth and their ready access to college draft deferments, or through desirable draft assignments as naval officers or reservists:

“If their IQs could be tested en masse, they would show native ability well within the top ten percent of all mankind…. Intellectually, they know a great deal. Practically, they choose to know almost nothing. For they have been subtly conditioned to believe (or, if not to believe, to sense) that the world is really quite irrelevant to them. And they are right…. They are invulnerable to the emotions of war.”[vi]

By contrast, a local police officer, Len Hendricks, who discovers the grisly remains of the shark’s first victim, is a Vietnam veteran. He is grateful to have a secure job. Trained as a radio technician, he struggled to find work in a glutted market after he returned home from Vietnam.[vii] In wartime Amity, the arrival of the shark is a catalyst for the town’s unraveling: the shark indiscriminately kills locals and summer people alike. Police Chief Martin Brody tries to close the beaches, but is repeatedly thwarted by Mayor Vaughn and his Mafia cronies. The novel is filled with political corruption, class conflict, racial strife, anti-Semitism, drug abuse, and marital infidelity. After Brody hires the crotchety sexagenarian seaman Quint to kill the shark, a tense confrontation erupts between Matt Hooper, the LaCoste-clad Ph.D. ichthyologist, and Quint over their firearms skills. The confrontation quickly turns to Vietnam: “Hooper didn’t know what Quint was doing either, but he didn’t like it. He felt he was being set up to be knocked down. ‘Sure,’ he said. ‘I’ve shot guns before.’ ‘Where? In the service?’ ‘No. I…’ ‘Were you in the service?’ ‘No.’ ‘I didn’t think so.’ ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Christ, I’d even bet you’re still a virgin.’”[viii]

Hooper and Quint are killed in pursuit of the shark. Only Brody survives. Published in the spring of 1974, the novel was an international bestseller. In the United States alone, the paperback sold over nine million copies.[ix] Benchley was amused to hear that Fidel Castro praised it as a wonderful metaphor for “the corruption of capitalism.” Jaws was also a bestseller in South Africa until it was banned under tightened censorship laws in 1975 for its salacious racial and sexual content.[x]

Even while Benchley was still finishing his “Untitled Novel,” he was working on an adapted screenplay for a movie version with Universal Studios. The movie became a dramatically different cultural product than the novel. Stripped of all references to Vietnam and contemporary socioeconomic conflict, the movie is a lean thriller centered on the rampaging shark and its climactic demise. Quint is now eaten by the shark—its final victim. But Hooper and Brody both live.

Despite the film’s erasure of Vietnam, the war provides an essential context for understanding the film’s reception in the summer of 1975. On April 29-30, North Vietnamese forces entered Saigon and dismantled the remains of South Vietnam, while the American evacuation mission, “Operation Frequent Wind,” frantically rescued Americans and South Vietnamese from the fallen city by helicopter. Just two weeks later, American troops were deployed again during the Mayaguez Incident in Cambodia. The last deaths of America’s longest war occurred in these final military operations.

Amid a jittery national mood, Jaws was released on June 20, 1975. The film was a smash hit, quickly creating a new cinematic category: the summer blockbuster. Directed by a virtually unknown twenty-eight-year-old named Steven Spielberg, Jaws grossed $60 million in its first month and became the most profitable film in American history (only to be displaced by “Star Wars,” two years later). Americans eagerly consumed Jaws paraphernalia: t-shirts, foam shark fins, and shark bones. Jaws terrified its audiences so completely that some coastal tourist towns experienced a recession. Frenzied swimmers occasionally became mobs as they fled the water, or even attacked harmless marine life thought to be sharks. On July 28, 1975, Newsweek dubbed this national hysteria, “Jawsmania.”

The shocks of war conditioned audiences for Jaws. Yet despite the film’s erasure of Vietnam, the movie explicitly remembered World War II in ways that the novel did not. In perhaps the film’s most haunting scene, just hours before his demise, Quint quietly recounts his experiences as a crewmember of the U.S.S. Indianapolis: “Soo, 1100 went in the water. 316 come out. The sharks took the rest. July 29, 1945. Anyway, we delivered the Bomb.”[xi]

The spring and summer of 1975 marked the thirtieth anniversary of America’s victory in World War II. Quint’s soliloquy reminded audiences of the “Good War,” a bygone era of national unity against a common fascist enemy. The movie’s unprecedented success also catapulted the stratospheric rise of Steven Spielberg, who would become, perhaps, the most influential architect of the nation’s cultural memory of World War II in subsequent decades. As the movie Jaws suggests, memorialization of the Good War could ease and recast the public’s memory of Vietnam.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following was originally presented to the roundtable: “The Vietnam War: Lessons and Legacies across a Half Century” Institute of Historical Studies, UT Austin, Thursday, November 12, 2015. Copyright © by Janet M. Davis

[i] David Morrell, forward, “Rambo and Me,” First Blood (1972, repr., New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2000), viii.

[ii] Morrell, xi.

[iii] Morrell, xii.

[iv] First Blood, directed by Ted Kotcheff (Orion Pictures, 1982), mojvideo.com.

[v] Box 1, I. Manuscripts, A. Books, 2. Novels, a. JAWS (Doubleday, New York, 1974), Folder 19, (ii) Drafts, (i) 4 pages of holograph title suggestions for JAWS, Peter Benchley Collection, #956 (cited hereafter as PBC), Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University (cited hereafter as HGARC).

[vi] Box 1, I. Manuscripts, A. Books 2. Novels, a. JAWS (Doubleday, New York, 1974), Folder 6, (ii) Drafts, (a) Rough partial draft, untitled, TS with holograph corrections, pp. 1-174, June 1972, p. 58, PBC, HGARC.

[vii] Box 1, I. Manuscripts, A. Books 2. Novels, a. JAWS (Doubleday, New York, 1974), Folder 6, (ii) Drafts, (a) Rough partial draft, untitled, TS with holograph corrections, pp. 1-174, June 1972, p. 14, PBC, HGARC.

[viii] Peter Benchley, Jaws (1974, repr., New York: Random House, 2005), 251.

[ix] Benchley, introduction, Jaws, 5.

[x] Benchley, introduction, 4; Erik van Ees, “South Africa: More Censors than Writers,” Montreal Gazette, October 17, 1975, https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1946&dat=19751017&id=YpMuAAAAIBAJ&sjid=WKEFAAAAIBAJ&pg=5335,537667&hl=en.

[xi] Jaws, directed by Steven Spielberg (Universal City Studios, 1975), DVD (Universal Pictures, 2012).

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.