Editor’s Note: To accompany this year’s Institute for Historical Studies theme and the theme of our film series Faces of Migration, Not Even Past will be showcasing a series of posts featuring graduate students working on topics related to migration, exile or displacement.

Nearly every historian can attest to the fact that working in the archives can lead you down unexpected paths that provide tantalizing, and often frustratingly abbreviated, glimpses into areas outside of their usual research. I had such an experience with a file that had the innocuous name “Near East Refugee Aid” one afternoon at the United Nations Archive in Geneva.

Near East Refugee Aid (NERA) was the name of a tiny League of Nations program that operated in the early- to mid-1920s. It consisted of only three agents—a director and secretary in Constantinople, and a female case worker based in Aleppo (now in Syria)—and operated on a tiny budget (none of its employees were paid). As I read through the documents in the file, I realized that NERA’s mission was far more specific than its name suggested: to seek out child survivors of the Armenian genocide.

The genocide began with the purge of prominent Armenian intellectuals and political activists by the Ottoman government in the spring of 1915. In the months that followed, the majority of Armenians residing in Asia Minor were rounded up and sent on forced marches toward the city of Deir ez-Zor, located in the Syrian desert along the Euphrates River. The vast majority of deportees never arrived, having been shot or hanged, or starved or frozen to death. Those few who managed to survive the trek found that almost no arrangements had been made to provide housing or other supplies for them once they arrived in Syria.

Armenians are marched to a nearby prison in Mezireh by Ottoman soldiers, 1915 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Estimates of the number of victims vary wildly. The Armenians claim over 1.5 million dead. While most historians—including a number of Turkish academics—recognize the events of 1915 as genocidal, the Turkish government does not and offers a revised death toll of around 700,000 (not coincidentally equal in number to the estimated Turkish civilian casualties during the war).

The documents in the NERA file complicated the usual polarized narrative of Turkish barbarism and Armenian suffering, and made the already tragic story even more heartbreaking.

NERA’s agents were looking for the children of Armenians who had been taken in by Turkish families. In some cases, Armenian parents left infants and toddlers with Turkish neighbors, coworkers, and friends who offered to take them in as deportation orders were issued. Other children were given away en route—sometimes, tragically, even sold—as their starving parents foresaw their own fates and desperately sought any chance for their children to live.

NERA’s mission was to find these children and, in the language of the Christian missionaries who staffed the organization, “to rescue them from Islam.” NERA’s reports laid out a narrative of victimhood: the children had been stripped of their identities, given new names, raised as Turkish speaking Muslims, forced to suppress their Armenian identities.

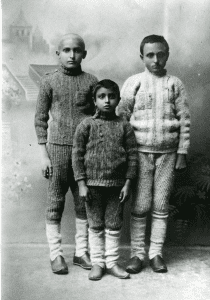

Armenian child refugees in cramped classrooms in Aleppo, 1915 (via Wikimedia Commons)

When NERA agents arrived in a town or village, some of the Turkish families came forward in hopes that their foster children might be reunited with their families, but others were quite reluctant to do so. It was unclear from the file what other methods NERA’s agents used to identify children suspected of being Armenian (neighborhood gossip appeared to be one source of information). Children would be summoned for an interview with a caseworker and an Armenian speaking volunteer. Since many of the children had been infants at the time and did not remember the Armenian language, more elaborate methods might be used. Children who could recognize traditional Armenian lullabies, for example, were assumed to be of Armenian origin. Once “recovered,” the children would be taken to a group home in Constantinople or Aleppo, until arrangements could be made to send them to relatives in Greece, France, or the United States.

While in some cases—usually those of children who were abandoned during the death marches—they had been treated as servants and never really considered part of the family, the opposite seemed to be true for those taken in by friends and coworkers in the child’s home town. However, NERA’s agents appeared to completely reject the idea the children might have formed a bond with the only family they had ever known. Some did not know they were not the natural born children of their Turkish parents. Tears and protestations of the Turkish parents at having the children taken away were usually dismissed as parlor tricks. In several cases police intervention was necessary to remove the children from their homes.

Armenian children in an orphanage in Merzifon, Turkey, 1918 (via Wikimedia Commons)

It was clear from the documents that the situation, which was represented by NERA as morally black and white, of rescuing Armenian children from “duplicitous” Turks, was far more complex in many cases. The traumatic effects on these children were clear from the file, although unrecognized at the time by the case workers on site. Some became violent and had to be restrained or sedated. A handful fled from the group homes and were eventually declared “lost.”

Frustratingly, the children’s stories contained in these files ended once they left Turkey. The file contained no information about what happened once they were reunited with relatives. Whether they fared well; if they kept in contact with their Turkish foster parents; or if any had eventually come back to Turkey to visit or live remains a mystery.

NERA’s work was short-lived, and came to an end toward the end of the 1920s, having successfully reclaimed just over one hundred children with relatives and, biases aside, provide a fascinating glimpse into the aftermath of the genocide. Several scholars (see note below) have begun working on the issue of Islamized Armenians living in Turkey after the genocide, and are contributing to a more nuanced analysis of what has become one of the most polarizing historical debates of the 20th century.

Related Reading:

A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire. Ronald Grigor Suny, Fatma Muge Göçek, and Norman M. Naimark, eds. Oxford: University Press 2011.

The preface and introduction to this book contain a recap of the differing interpretations of the events of 1915, the suitability of the term “genocide” to describe them, and a survey of differing narratives and those who support them.

While, to my knowledge, there has been no scholarly study regarding NERA’s work specifically, a summary of major works regarding Islamized Armenians in Turkey after World War I can be found in Ayse Gül Altinay, “Gendered Silences, Gendered Memories: New Memory Work on Islamized Armenians in Turkey,” Eurozine (2014), accessed September 16, 2017.

Of particular note:

Vahé Tachjian , “Gender, Nationalism, Exclusion: The Reintegration Process of Female Survivors of the Armenian Genocide,” Nations and Nationalism 15, 1 (2009): 60–80

Ayşeynur Korkamaz, “’Twenty-five Percent Armenian’: Oral History Accounts of the Descendants of Islamized Armenians in Turkey,” unpublished Master’s thesis, Central European University, 2015.

Also by Christopher Rose on Not Even Past:

Mapping & Microbes: The New Archive (No. 22)

Exploring the Silk Route

Review: The Ottoman Age of Exploration (2010) by Giancarlo Casale

What’s Missing from Argo (2012)

You may also like:

Kelly Douma reviews Justifying Genocide: Germany and the Armenians from Bismarck to Hitler (2016) by Stephan Ihrig

Andrew Straw on the Tatars of Crimea: Ethnic Cleansing and Why History Matters

Check out the schedule for our film series “Faces of Migration: Classic and Contemporary Films”

More on this year’s Institute for Historical Studies theme “Migration, Exile, and Displacement”