A few weeks ago José Salvador Alvarenga drifted onto a small island in the South Pacific Ocean in a worn-out, 24-foot long, fiberglass boat, wearing nothing but a tattered pair of underpants. With the aid of a Spanish interpreter, Alvarenga explained to surprised locals that he had been lost at sea for at least sixteen months after his fishing boat was pushed out to sea off the coast of Mexico. He said that he stayed alive by catching and eating raw fish, turtles, and birds.

Media outlets around the world have rushed to tell Alvarenga’s amazing story of survival, but from the beginning they have doubted the veracity of the fishermen’s version of events. Underlying the media’s skepticism is the belief that it is simply not possible for a human to survive for so long at sea without food and fresh water.

Jose Salvador Alvarenga, who spent 13 months on a remote Pacific island, after being rescued. (Image courtesy of Mashable)

One Fox News article asked, “Was it all a mirage?” The Sydney Morning Herald described Alvarenga’s story as “a tale of ocean survival that smells a bit fishy.” Searching for holes in Alvarenga’s story, a number of reports pointed out that Alvarenga was rather plump for someone who had been through such an ordeal (Doctors later confirmed that his paradoxically bloated appearance is consistent with a state of long term starvation).

One Fox News article asked, “Was it all a mirage?” The Sydney Morning Herald described Alvarenga’s story as “a tale of ocean survival that smells a bit fishy.” Searching for holes in Alvarenga’s story, a number of reports pointed out that Alvarenga was rather plump for someone who had been through such an ordeal (Doctors later confirmed that his paradoxically bloated appearance is consistent with a state of long term starvation).

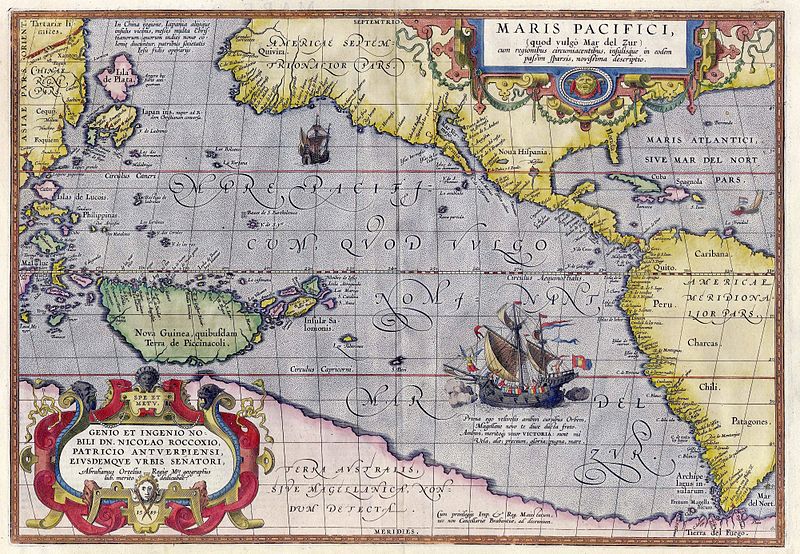

Could Alvarenga really have drifted for 8000 miles from Mexico to the Ebon atoll in the Marshall Islands? If we look into the history of the great Pacific Ocean, we find several stories of survival that suggest Alvarenga is telling the truth.

In his famous history of The Manila Galleon, William Lytle Schurz talked about the survivors of one of these large Spanish treasure ships that was lost crossing the Pacific from Mexico in 1693. Two men made it all the way to the Philippines in conditions similar to what Alvarenga endured (thanks to Steph Mawson for this reference). The Galleon‘s

fate was eventually learned from two men picked up long after near the town of Binangonan de Lampon. In the boat in which they had managed to reach the Philippines was the corpse of a dead companion. One of the two survivors had gone stark mad from his sufferings. Before the burning galleon had foundered six men put off from her side in an open boat and headed westward. After three weeks their food gave out and two of the starving men slid over the gunwales into the sea. Those who were left then ate their jackboots and their belts to stave of starvation. At last it was decided to draw lots as to which of the four should be eaten by the rest. One of the three preferred to starve rather than to turn cannibal. It was only the last two who survived these horrible experiences, one without his reason, the other broken by his sufferings and long under the shadow of the Church for having partaken of human flesh.

Maris Pacifici by Abraham Ortelius (1589), the first printed map of the Pacific and the Americas. (Image courtesy of Helmink Antique Maps)

Perhaps the most famous Pacific castaway is the British Naval Captain William Bligh. In 1789, Bligh and eighteen of his men were forced to disembark from Bligh’s ship The Bounty and climb into a 25-foot long launch boat; a tiny vessel intended for carrying people and supplies from ship to shore. The mutineers surely believed that their deposed Captain and his supporters faced a certain death. Yet over the next forty-seven days, Bligh used a quadrant and a pocket watch to navigate the very crowded launch from near Tonga to the Dutch settlement at West Timor, a 4350 mile journey.

Amazingly, only one man died on this voyage. Greg Denning’s history of the mutiny Mr Bligh’s Bad Language: Passion, Power and Theatre on the Bounty wrote that:

“From [Bligh’s] careful record of every item consumed … the total food each man had in forty-eight days was this: seven pounds bread, one pound salt pork, one pint rum, five ounces wine, two and one-quarter coconuts, one banana, one pint coconut milk, one and one-quarter raw seabirds, four ounces fish … A sailor’s ordinary food allowance has been calculated at about 4,450 calories a day. On the figures I have given here a nutritionist estimates that the launch people were reduced to 345 calories a day. This would mean a possible daily energy deficit of 4,105 calories and a total weight loss of 56 pounds.

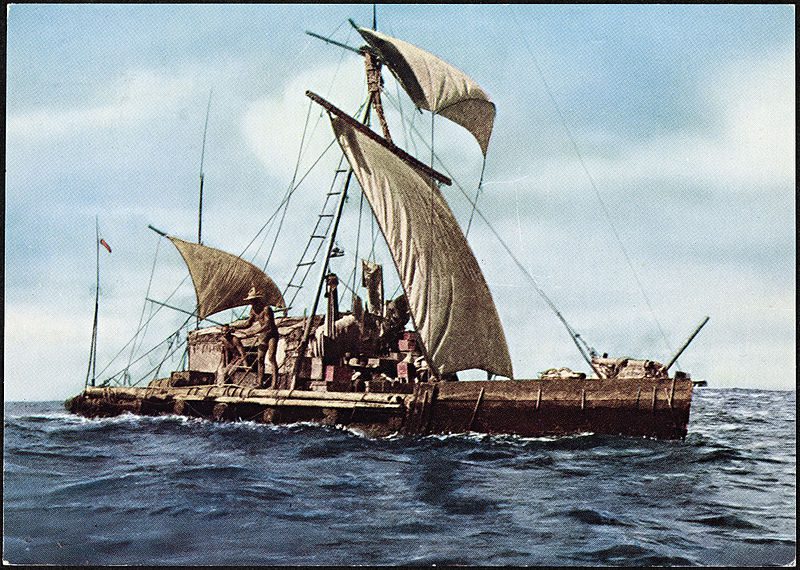

In 1947, the intrepid Norwegian anthropologist Thor Heyerdhal and five other men crossed the Pacific Ocean from Peru to Polynesia in a small, balsa-wood raft named “Kon Tiki” that Heyerdhal built with his own hands. The boat was a replica of a pre-Inca raft, and the purpose of this dangerous exhibition was to prove Heyerdhal’s theory that it was the South Americans who first discovered and populated Polynesia thousands of years ago using similar vessels.

Although the Kon Tiki’s voyage doesn’t exactly prove Heyerdhal’s origins theory, (which for most scholars doesn’t hold water), the fact that six men completed a 101-day long, 4300-mile voyage on a 40 square-foot raft was at the time, and continues to be, a pretty exciting feat. The raft didn’t have oars and couldn’t really be steered in any direction. Although the Kon Tiki was equipped with US army supplied food, the crew reported a rich supply of fish (and sharks!) in the warm-water currents that carried them to Polynesia. If you are interested in Heyerdhal’s adventure, the story of the Kon Tiki is told in Joachim Rønning and Espen Sandberg’s 2012 film, which is currently available on Netflix.

After reading this piece, you might agree that Alvarenga deserves an apology from the news outlets around the world who rushed to accuse the fisherman of fabricating his story. We historians of the Pacific world know that the history of this largest ocean is punctuated by amazing stories of survival that should be celebrated.