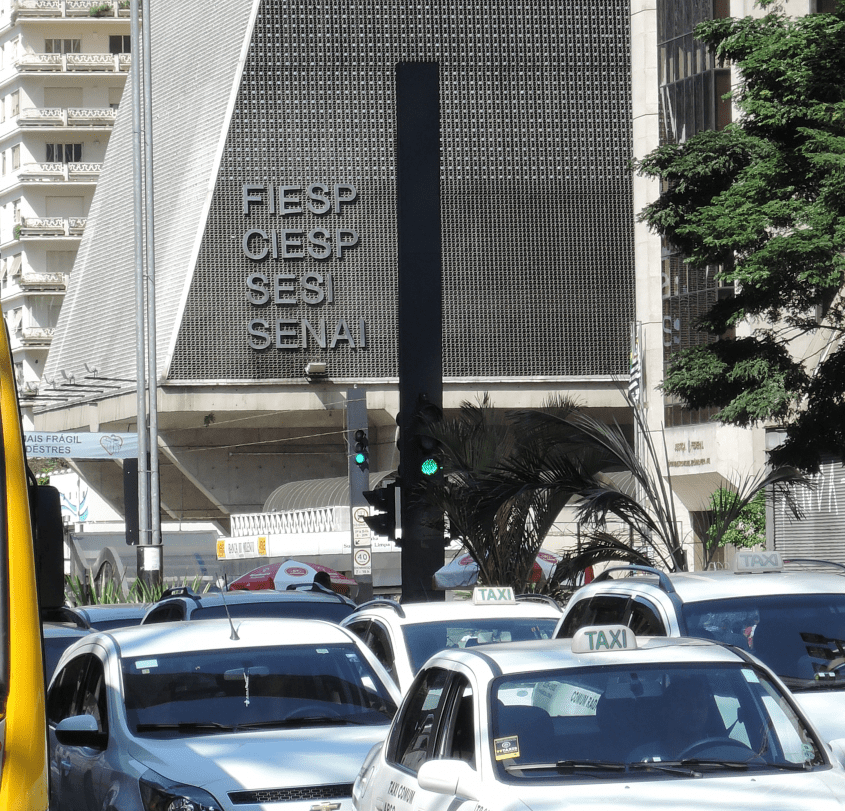

In this rightfully celebrated book, Barbara Weinstein explores the efforts of São Paulo’s industrial elite to shape and control the Brazilian workforce from the 1920s to 1964 through two government-established yet privately-controlled public agencies—the National Service for Industrial Training (SENAI) and the Industrial Social Service (SESI).  Founded during the 1940s, these agencies were the vessels through which Paulista industrialists, technocrats and educators advanced their agenda of “rationalized organization” and “scientific management,” promoting the idea that professional authority and technical expertise were necessary to modernize Brazilian society.

Founded during the 1940s, these agencies were the vessels through which Paulista industrialists, technocrats and educators advanced their agenda of “rationalized organization” and “scientific management,” promoting the idea that professional authority and technical expertise were necessary to modernize Brazilian society.

Employing discourse analysis to examine an astounding number of primary sources—interviews, newspapers, bulletins, periodicals and government records—Weinstein traces the origins, roles and reception of SENAI and SESI. She begins by reviewing the influence of early twentieth-century ideas about work organization such as Taylorism, Fordism and applied psychology on São Paulo’s new generation of postwar industrialists. Her analysis of newspapers published by the industry’s associations demonstrates how a “rationalization discourse” that emphasized national progress through industrial development, began to appeal to influential figures. They “found rational organization a guide to the construction of a sanitized, orderly urban society in which they would provide the crucial technical expertise.”

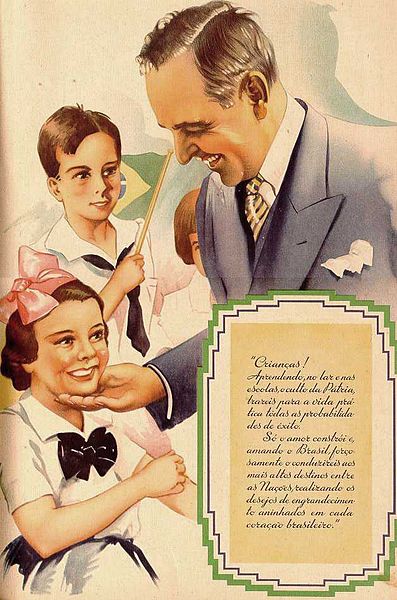

The Brazilian state was never preoccupied with mediating labor demands until Getúlio Vargas’ presidency. During Vargas’ Estado Novo, however, the regime enacted federal legislation to regulate labor and capital, and to resolve workers’ grievances. Industrialists, for their part, did not appreciate the state’s efforts to control their businesses and protect workers’ rights.Out of that conflict came SENAI (Serviço Nacional de Aprendizagem Industrial) in 1942 and SESI (Serviço Social da Indústria) in 1946, both decreed by the federal government but operated by associations of industrialists. SENAI, self-defined as a “practical training” agency, promoted scientific management and vocational training; SESI, which Weinstein considers more ideologically motivated, administered welfare and educational programs that aimed to battle the influence of leftist and communist-leaning labor initiatives.

Propanganda poster of Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas meeting young children (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

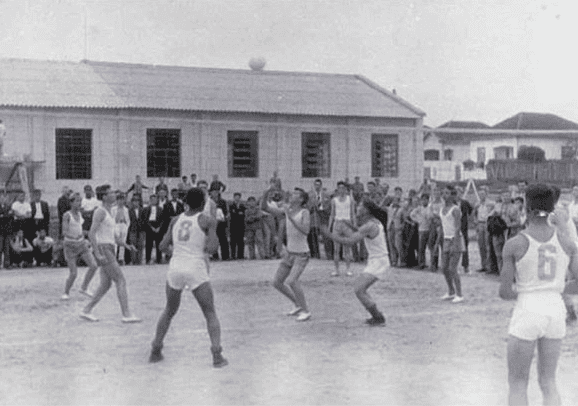

Volleyball game at a SENAI industrial school between students from Curitiba and Londrina, 1950 (Image courtesy of The Scientific Electronic Library Online)

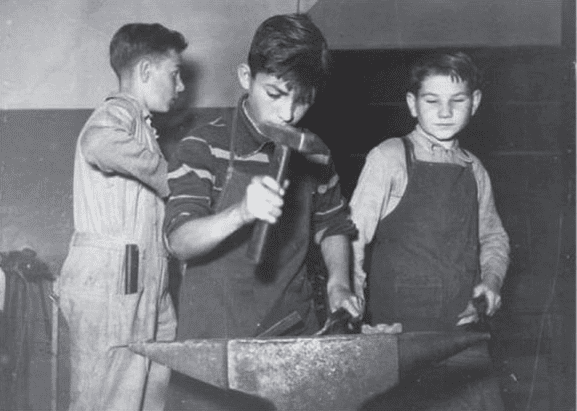

The nuanced examination of SENAI and SESI programs is perhaps the most fascinating part of the book. More than examining the ways in which workers’ skills and behavior were shaped, Weinstein illuminates the workers’ role in constructing the hegemonic relationship between the laboring and the industrialist sectors. Through training sessions, SENAI instilled the “appropriate” conduct of workers at the workplace, creating skilled (and semiskilled) workforce that raised levels of productivity. Accompanying this, SESI established recreational sports clubs, which according to Weinstein aimed not only to win the loyalty of the working class but also to prevent militant workers from organizing and consequently damaging productivity. Yet the agencies’ concern was not limited to what was happening on the factory floor. SESI also intervened in the household, where social workers, counselors and magazines both advanced the “proper ideals” and responsibilities of the housewife, father and children, and promoted budget planning as a solution to workers’ grievances regarding low wages. Good management was seen as the perfect panacea.

Children learn blacksmithing at a SENAI industrial school, sometime between 1943 and 1950 (Image courtesy of The Scientific Electronic Library Online)

These initiatives were successful in preventing intense class conflict between 1920 and early 1960s. Weinstein demonstrates that industrialists were not the only ones to adopt the rationalizer’s discourse. Workers and labor leaders were not only receptive to programs that offered secure salaries and occupational health, they also took pride in their role as key agents of progress, modernizing the Brazilian economy and society. By the early 1960s, however, labor organizations began to show signs of defiance to the process of cooptation and intervention in factory life. In response to workers’ unrest, industrialists turned to support an authoritarian ideology. The change was expressed through SENAI and SESI covertly supporting the 1964 military coup, and embracing the repressive programs of the regime for “social peace.” On the other hand, the industrialists’ modernization project—aimed to create a progressive and productive labor force—did not necessarily produce submissive workers. As Weinstein notes in her concluding chapter, a surprising number of SENAI graduates played leading roles in the revival of labor activism during the 1970s and 1980s, among them former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Contemporary photograph of the São Paulo building housing the SENAI and SESI agencies (Image courtesy of Eyal Weinberg)

For Social Peace offers a large-scale, yet in-depth, analysis of the development of the urban laboring sector in Brazil during the first half of the twentieth century and the role the Brazilian industrialist elite played in the country’s modernization process. Its nuanced interpretation, illuminating both workers’ acceptance and their uncertainties regarding the efforts for rationalism and progressivism, is still, seventeen-years after its publication, a well-deserved foundation to the field.

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines

**

You may also like:

Darcy Rendón’s review of Laws of Chance: Brazil’s Clandestine Lottery and the Making of Urban Public Life

And Franz D. Hensel-Riveros’s review of Hello, Hello Brazil: Popular Music in the Making of Modern Brazil