by Travis Gray

Stalin’s Genocides provides an in-depth analysis of the horrendous atrocities — forced deportations, collectivization, the Ukrainian famine, and the Great Terror — perpetrated by Joseph Stalin’s tyrannical regime. Norman Naimark argues that these crimes should be considered genocide and that Joseph Stalin should therefore be labeled a “genocidaire.” He presents four major arguments to support this claim. First, the previous United Nations definition of genocide has recently been expanded to include murder on a social and political basis. Second, dekulakization—the arrest, deportation, and execution of kulaks or allegedly well-off peasants—was a form of genocide that dehumanized and eliminated an imagined social enemy. Third, during the Ukrainian famine in 1932-1933, victims were deliberately starved by the Soviet state. Fourth, The Great Terror was designed to eliminate potential enemies of the Soviet Union. Overall, Naimark’s arguments are persuasive, presenting a chilling portrait of Joseph Stalin as a sociopath bent on destroying his own people.

Naimark begins with a brief consideration of “genocide” as a legal term in international law. Although the UN’s Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide does not apply to political or social groups, he shows—rather successfully—that the original UN definition of genocide had included these groups, but that the Soviet delegation had prevented this language from being adopted. This definition, however, has been challenged since the fall of the Soviet Union. Indeed, there have been recent cases in the Baltic states where individuals have been convicted of genocidal crimes for deporting and murdering social and political groups. Because these cases are bound by the precedents of international law, they provide historians with an opportunity to analyze Stalin’s crimes within a broadened definition of genocide that includes political and social groups.

Using this broader definition of genocide, Naimark proceeds to analyze instances of mass killing in the Soviet Union. His chapter on dekulakization is particularly persuasive as an instance of genocidal extermination both planned and implemented by the state to control its rural population. He makes the important distinction that although “the kulaks” were not a conventional social group, they “became an imagined social enemy” whose members experienced the same forms of violence and dehumanization faced by other ethnic and national groups (56). In this regard, dekulakization was similar in both form and function to internationally recognized instances of genocide in Germany, Rwanda, and Yugoslavia.

Naimark’s last two arguments regarding the Ukrainian famine and the Great Terror are less convincing. Although there is a lot of evidence to indicate that Stalin and his lieutenants were directly responsible for generating both the famine and the terror, neither of these events seems to have been intentionally designed to eliminate a particular group. Repression during the Great Terror, for example, was often applied randomly throughout the Soviet Union with little consideration given to the victim’s political, social, national, or ethnic identity. Likewise, it can be argued that the famine was used as a weapon against Ukrainian nationalism, but Naimark offers no convincing evidence to suggest that Stalin used the famine as a way to destroy the Ukrainian peasantry.

In sum, this book provides the reader with deep insight into the nature of Stalin’s crimes. It helps characterize one of history’s greatest mass murderers in a new light—as a genocidaire whose crimes should be condemned in the harshest terms. Even though the term genocide may not be appropriate in all the examples cited by Naimark, the book prompts historians to discuss the issue of genocide outside the confines of the Holocaust—a topic that many scholars have been eager to avoid.

Photo Credits:

Ukrainians in Kharkiv pass by a starving man during Holodomor, the Ukrainian famine, 1932 (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

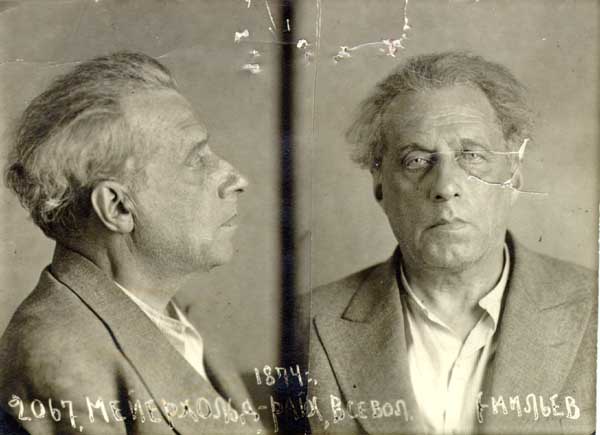

Mug shot of Russian theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold after being arrested in 1939 amidst Stalin’s Great Purge of artists and intellectuals (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

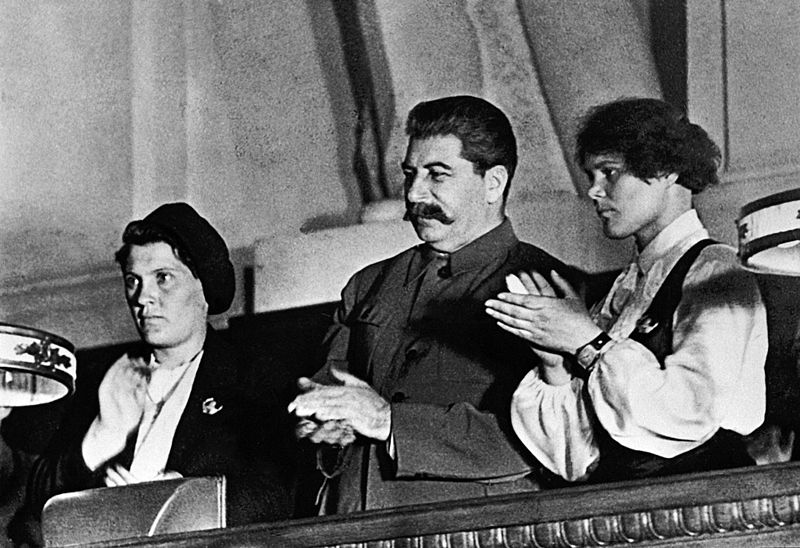

Joseph Stalin at the Congress of the Young Communist League with two “famous” collective farmers: Praskovya Angelina (left), founder of a female tractor team and Maria Demchenko (right), an innovative beet grower (Image courtesy of Russian International News Agency (RIA Novosti) / RIA Novosti archive, image #377427 / Shagin / CC-BY-SA 3.0)