By Erika Bsumek and Kyle Shelton

As students begin to contemplate which classes to take during the spring semester, many will ask themselves what’s the point of a liberal arts education? Why study history, literature, philosophy and “soft” sciences like sociology and psychology when science, technology, engineering and math seem to dominate our futures?

Both STEM and the Humanities are essential to understanding our society and building for the future and they ought to be better integrated. The Humanities teach us how to think critically about the challenges relevant to all of us, including engineering and technology problems. Our deteriorating infrastructure, for example, lies in the hands of our future engineers. But as our roads, bridges, and dams continue to receive poor marks on the American Society of Civil Engineers report card, we can best rebuild only if we understand the infrastructure’s history and the social, economic, and cultural context we are building in. It’s time to help humanities students better understand how to engage with the physical world around them and to introduce critical social and cultural studies to engineering students. Bridging these disciplines can help all students recognize and grapple with the fact that seemingly divergent fields overlap in significant ways. One recent American Academy of Arts and Sciences study notes the importance of integrating “the sciences, social sciences, humanities and artistic practice” in order to “serve our students better.”

In the spring of 2014 we taught a new undergraduate history class at UT Austin called “Building America: Engineering Society and Culture, 1868-1980,” intended to bring STEM and Humanities students together. One of the main goals of the class was to teach Humanities students how the technology surrounding them works and to teach STEM majors how history shapes technological advances.

“Building America” examines roughly 100 years of construction and engineering projects in American society from the late 1860s through approximately 1980. The key mission of the course is to appeal to a wide variety of students from across campus but especially to draw engineering students who often do not get the chance to take required general education courses until the last semester of their senior year. The class helped examine the work of politicians, architects, engineers, urban planners, naturalists, and reformers. We studied the complex relationships between large-scale infrastructure projects, the technologies those projects required, and the social developments that brought the projects into being and changed in their wake.

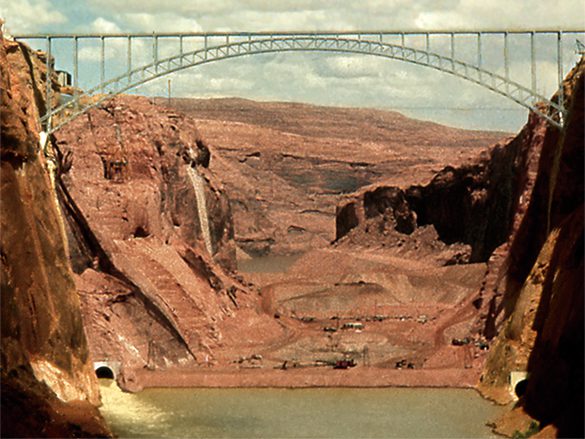

Night view of Glen Canyon Dam and all four jet tubes open releasing water during high-flow experiment – March 5, 2008 (Courtesy of the Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation).

The course filled quickly during registration, indicating that the subject appealed to a diverse collection of students and their enthusiasm didn’t wane. STEM students seemed hungry for ways to place the technical skills they had been acquiring into a broader social context. Rather than take a “march through time,” approach, the course focused on five different infrastructure projects—including the Interstate Highway system and Glen Canyon Dam—and the ways they transformed business and engineering practices as well as art, design, and the allocation of resources.

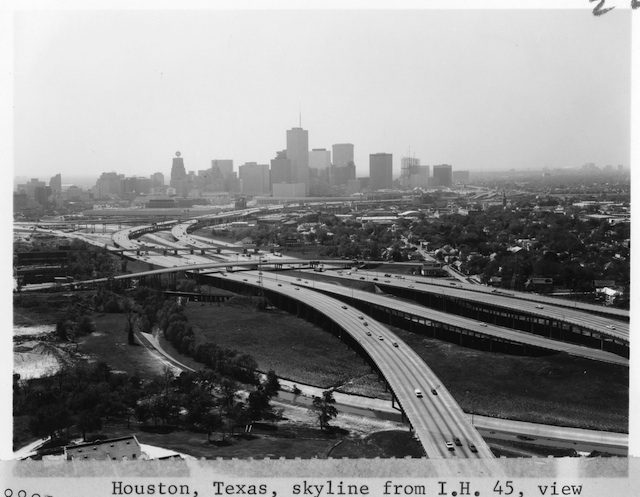

View of the I-45 in Houston prior to redevelopment (Courtesy the State of Texas Department of Transportation)

Students from both STEM and Humanities backgrounds said that they found the class much more relevant than typical history survey courses. A senior nursing major noted that the class illuminated connections between the past and present in the built environment, which gave her a totally new perspective on the relationship between the environment and health that was missing from her other courses. Another student recalled that the course worked for him because his STEM professors only rarely addressed the ways engineering concepts affected society. They only discussed “how things worked, not where they fit” in society.

View of the I-45 in Houston after redevelopment (Courtesy the State of Texas Department of Transportation)

Engaging with the history of the built environment helps students from across the large UT community realize that infrastructure matters to everyone: not just urban planners and policy makers. Both at the university and beyond, we have a tendency to artificially compartmentalize the world into discrete disciplines. Our classroom served as a place to connect, rather than divide. This approach offers a replicable opportunity to engineer a solution to the problem of disciplinary stratification that threatens to devalue the Humanities and sterilize the specialized training of STEM students.

Bringing disciplines together in a Humanities classroom and using that space to push students to ask probing questions about their lives, their studies, and their society, does more than add to a toolkit of job skills. It builds up the students’ curiosity and understanding about the world around them and helps them see that building a bridge may require more than solving a set of technical problems. It also means asking a set of questions about what we value in society.

Authors:

Erika Bsumek, an associate professor of history at the University of Texas, researches the impact that large construction projects (dams, highways, cities and suburbs) had on the American West. She is currently working on a book titled “The Concrete West: Engineering Society and Culture in the Arid West, 1900-1970.”

Kyle Shelton, a postdoctoral fellow at the Kinder Institute for Urban Research at Rice University, finished his PhD in American History in May 2014 and was the graduate teaching assistant for Bsumek’s “Building America” cours