by David Ochsner

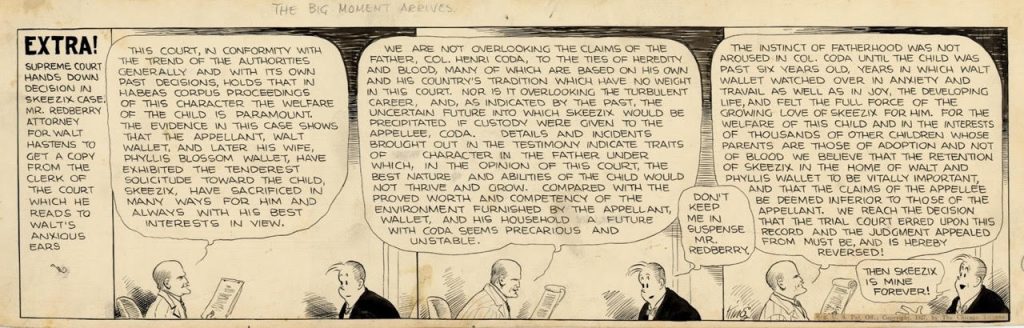

Interminable…The last thing Dorothy Parker wanted in her funnies was some fine print. In Frank King’s Gasoline Alley strip from 1927, Walt gets full custody of the orphan Skeezix (via hoodedutilitarian.com)

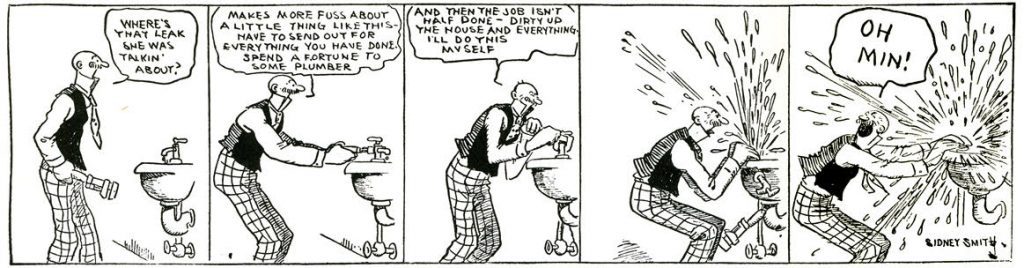

“It is amazing, it is even a little terrifying to see how the spirit of the comic strip has changed,” wrote Dorothy Parker in her Dec. 3, 1927 “Reading and Writing” column for The New Yorker. Time was, she lamented, when the daily strips concerned themselves “with chubby children blowing their elders to hell with generous charges of dynamite,” and “each set of pictures ended gloriously, with a Bam and Pow, in the portrayal of the starlit delirium induced by a cracked skull.”

Dorothy Parker in the 1920s (via Wikipedia)

Most of us know Parker as one of America’s great satirists and a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table. She could also be a tough critic. No author was sacred in her book review column, which ran in The New Yorker from 1927 to 1931. She summed up the beloved “Pooh” poems in A.A. Milne’s Now We Are Six as “affected, commonplace, bad,” and when Sinclair Lewis published The Man Who Knew Coolidge, she dismissed it as “an outrageously irritating book.”

So it was a bit of a surprise to discover that Parker was also a dedicated reader of the funny pages, which doubtless offered her respite from the bouts of depression she suffered throughout her life. When favorite strips such as The Gumps abandoned broad humor in favor of long-form melodrama, Parker was crestfallen, lamenting that she hadn’t “seen a Pow or a Bam in an egg’s age.”

Andy Gump, in simpler times, from a 1920 strip featuring The Gumps, by Sidney Smith (via newspapers.com)

Sidney Smith, creator of The Gumps, is often credited as the originator of the comic strip melodrama. Unlike a daily, stand-alone gag, this serial approach kept readers waiting for the next installment. Smith was also the first cartoonist to kill off a regular character. His “Saga of Mary Gold,” which ran during 1928-29, ended with sweet Mary’s tragic death and prompted a flood of letters from readers demanding her resurrection.

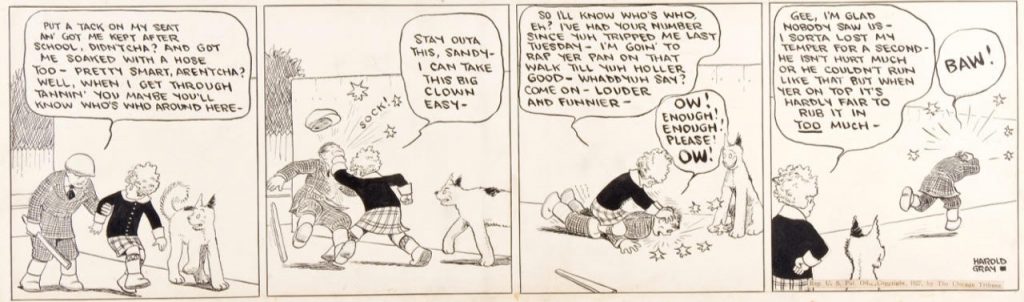

Busying himself with charity work while being mixed up with spies, Andy Gump had “lost his touching and epic sympathy,” Parker wrote. On top of that, Little Orphan Annie had also gone soft, Annie helping a widowed neighbor with her housework rather than “fighting various gangs of desperadoes.”

Not Your Broadway Annie…Before she went domestic, Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie could kick some butt, as she did in this 1927 strip

Over in Gasoline Alley, a gag strip that featured the simple life of guys and their cars, the strip’s creator, Frank King, was allowing his characters to age naturally. “That hurts, Parker wrote. “We ask our comic artists for bread, and they give us realism.” She lamented the strip’s “interminable” storyline, which at the time was mired in a custody battle in which “Unca Walt” (the strip’s patriarch) was desperately trying to adopt little Skeesix, who had been left on Walt’s doorstep in a 1921 strip. Parker feared that by the time the custody battle was settled, “Skeesix is going to be a kindly old gentleman with a flowing beard” (Skeesix, now 96, is still occasionally featured in the strip).

Parker concluded that the melodramatic comics “are unquestionably what the readers want,” and was “surely indicative of something…I cannot bear to analyze it. My great heart is broken for my people. What this country needs is more Bams and more Pows.” If Dorothy were still around today, she would find plenty of Bams and Pows at the Multiplex.

David Ochsner writes the blog, A New Yorker State of Mind, in which he chronicles his experiences reading every issue of the New Yorker magazine. He is currently mired in the fall of 1928.

Also by David Ochsner on Not Even Past:

Reading Every Issue of the New Yorker

You may also like:

Hearing the Roaring Twenties: The New Archive (No. 12)

The Civil War, as seen by the artists of Harper’s Weekly

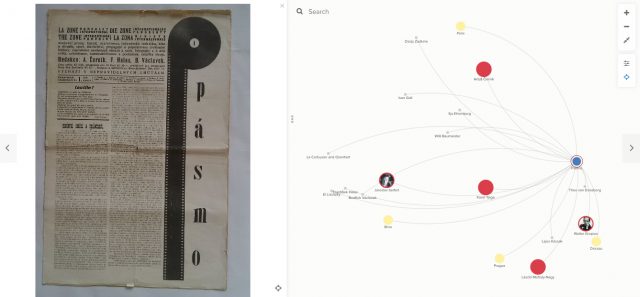

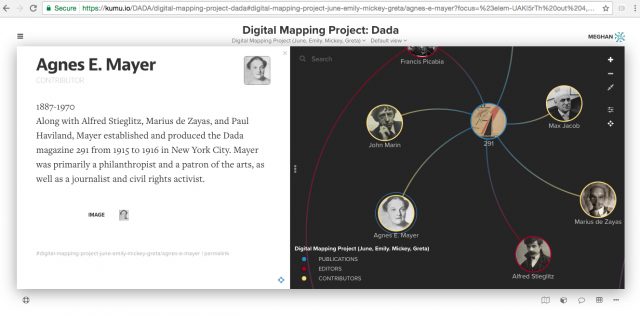

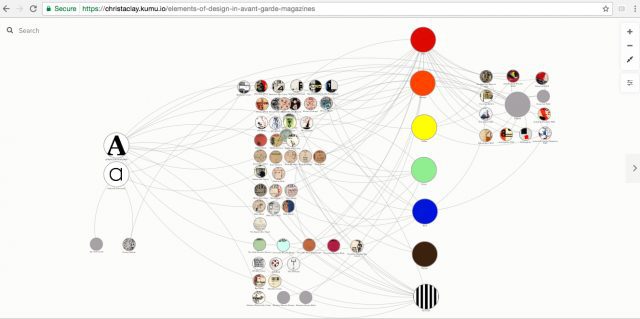

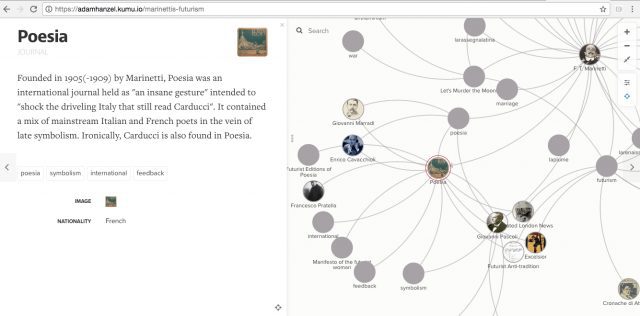

Digital Teaching: Mapping Networks across Avant-Garde Magazines

Media and Politics From the Prague Spring Archive, by Ian Goodale