A German novelist and screenwriter, Norman Ohler first happened upon the topic of drug use in the Third Reich through a Berlin-based DJ, who told him that drugs were widespread at the time. Intending to write a novel on the subject, Ohler went into the archives in search of historical detail for his book. What he found in military records and the personal papers of Hitler’s physician was so astounding that Ohler left the world of fiction to write a work of history.

A German novelist and screenwriter, Norman Ohler first happened upon the topic of drug use in the Third Reich through a Berlin-based DJ, who told him that drugs were widespread at the time. Intending to write a novel on the subject, Ohler went into the archives in search of historical detail for his book. What he found in military records and the personal papers of Hitler’s physician was so astounding that Ohler left the world of fiction to write a work of history.

The result is the highly readable, bitingly ironic Blitzed, that, although not without problems, lends a fresh perspective on Hitler and the Second World War. In sum, Ohler aims to show that drug use was rife in Nazi Germany. From its rise through to its collapse, German citizens were high, German soldiers were high, and Hitler was high.

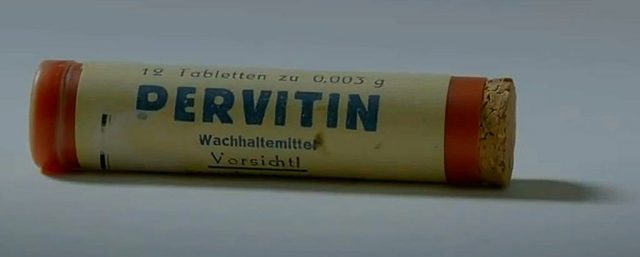

In the 1920s, many Germans turned to artificial stimulants to cope with the trauma of WWI, Ohler argues, and eventually Nazi promises of collective ecstasy and euphoria became like a drug itself. In 1937, in a pharmaceutical factory not far from Berlin, the pharmacist Dr. Fritz Hauschild found a drug to match the social intoxication of the time: Pervitin.

The first German methylamphetamine, Pervitin was a performance-enhancing drug that gave the consumer an “artificial kick” of heightened energy, alertness, euphoria, and intensified senses, often lasting more than 12 hours. Pervitin was marketed to Germans as a panacea cure for anything from depression to “frigidity” in women. By 1939, the drug was also distributed among German army battalions as they swept through Poland and France without sleep and without halt.

The “people’s drug:” Pervitin (Karl-Ludwig Poggemann via Flickr)

Ohler even goes so far as to say that the use of Pervitin was crucial to Germany victory in France in 1940. The German surprise-strategy to drive tanks through the Ardennes – later coined the “sickle cut” by Winston Churchill – was a near-impossible operation, argues Ohler, that only stood a chance if the Germans could drive day and night without stopping. Learning from the use of Pervitin during the Polish campaign, army officials realized that overcoming fatigue was just as crucial as tactic and equipment. The Wehrmacht ordered 35 million tablets for the campaign.

Critics have pointed out that Ohler tends to make sweeping generalizations. Does the evidence he presented, in fact, allow Ohler to say that many or most German citizens and soldiers were taking methylamphetamines? In a scathing review, historian Richard J. Evans wrote that Ohler severely overstates the role of drugs in both civil society and the military effort. “To claim that all Germans, or even a majority of them, could only function on drugs in the Third Reich,” writes Evans, “is wildly implausible.” While it may be difficult to pinpoint how many ordinary Germans took Pervitin, Ohler makes a convincing case for its methodical use and central role in the 1940 campaign.

Hitler and his entourage at the Wolf’s Lair, June 1940. Hitler’s personal physician, Dr. Theodor Morell, stands in the second row, second from the right (via Bundesarchiv)

The second issue that Ohler addresses is that of Hitler’s drug use. Fearing illness and an inability to perform, Hitler sought out performance-enhancing remedies that came in the form of vitamin injections and glucose solutions from Dr. Theodor Morell, his personal physician who saw and treated him more or less daily from 1936 until the end of the war. By 1944, Ohler argues, Hitler was addicted to a mix of cocaine and Eukodal (an opiate), assumed to be marked by an ‘X’ in Morell’s charts. When Eukodal supplies began to run out by February 1945, Hitler began suffering withdrawal symptoms.

Ohler’s assertion that Hitler was a drug addict has roused the ire of some historians, notably Evans, who has dismissed Ohler’s claims as a “crass,” “inaccurate” and morally problematic account that excuses Hitler of his own behavior and crimes. But, that does not seem to be Ohler’s argument here. Blitzed does not propose to reshape our understanding of Hitler’s psyche or ideology, but rather to understand the elements – including drug consumption – that held Hitler firmly in a world of delusion that ultimately prolonged the Second World War. Historians including Anthony Beevor and Ian Kershaw consider Blitzed a valuable addition to scholarship that is not apologetic, but illuminative.

Perhaps the debate about Blitzed is not only about our understanding of Hitler and National Socialism, but also about who gets to contribute to the already well-trodden scholarship. In his review, Evans expressed concern that Ohler’s background as a novelist gives him a “skewed perspective.” But the perspective of an outsider may be what the discipline needs. Blitzed allows the general reader to learn about a well known period in a new light, while also offering new lines of inquiry for scholars. A meticulously researched and bold work, Blitzed is a must-read for the general reader and scholar alike.

More by Natalie Cincotta on Not Even Past

Veiled Empire: Gender and Power in Soviet Central Asia (Review)

Kevin Baker reviews Omer Bartov’s Hitler’s Army

David Crew discusses the work of German propaganda photographers during the Second World War

Chris Babits on finding Hitler (in all the wrong places)