In 1849, sixty-five “ladies of Fayette County” Tennessee wanted their State legislature to know that a central dimension of patriarchy was failing. In a collective petition, they highlighted the ways that this failure was unfolding and how it impacted the lives of Tennessee women, particularly those who were married or who were soon to be wed. At the center of their petition were “thoughtless husbands” who fell far short of patriarchal ideals. These men, through “dissipation or improvident management,” created circumstances that compelled their new wives to endure lives plagued by “destitution,” “hardship, and suffering.”

The signatories went on to draw astonishing contrasts between the patriarchs of old and those of a new age and the ways that these different generations of men treated the women in their lives. The young women they purported to represent entered marriages with “competent estates descended to them from the estates of their deceased fathers,” noblemen who accumulated their wealth and property through years of labor, diligence, and frugality. They waxed nostalgic about those hardworking men of their father’s generation who hoped to pass the fruits of their extensive and admirable efforts onto their children. Yet, within no more than two years of marriage, they alleged, their husbands had wasted it all. Playing to the legislature’s fatherly sentiments, the Fayette County ladies told its members that the men whom they entrusted their daughters to were inept, thieving failures who stole their fortunes and financial legacies and left their most vulnerable children in “want and suffering.”

The legal doctrine of coverture and the constraints it imposed upon married women were central to the failures of which they spoke. Coverture provided that when a woman married, her assets or wages became her husband’s. If she acquired any property after she married, those assets would belong to her husband as well. In other words, the legal doctrine of coverture robbed married women of their independent legal and economic identities.

These sixty-five Fayette County women challenged the tenets of coverture and asked the legislature to consider whether the elements of this legal doctrine were “based on the principle of equity and justice.” They queried whether it was “right and justice to subject the patrimony of married Ladies to the payment of the debts of the husbands which often exist before marriage.” Their line of questioning made it clear that, in their eyes, it was not. They called upon the legislature to “devise and enact some Law for the State” whereby “the personal estates of females [would] be placed upon a similar basis as their Real estate, and so protected and secured that it cannot be sold, and taken from them without their consent.”

There was a specific reason why they deemed this “placement” necessary: slavery and the region’s dependency upon it. Slave-owning parents typically gave their daughters more slaves than land, and as a result, slaves were profoundly important to women’s personal stability. These women asked the legislature to protect the kind of property that was worth the most to them because, in light of “peculiar Southern institutions, manners, and customs, it [wa]s in most cases a much greater privation and inconvenience to the married ladies to be deprived of their slaves than of their land.”

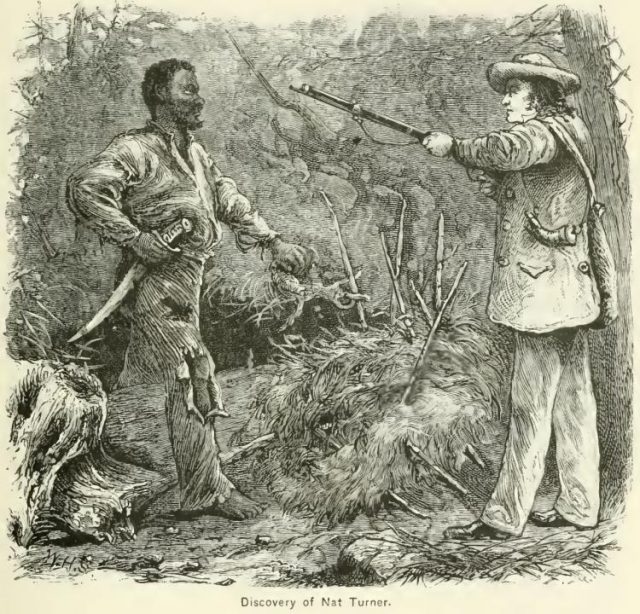

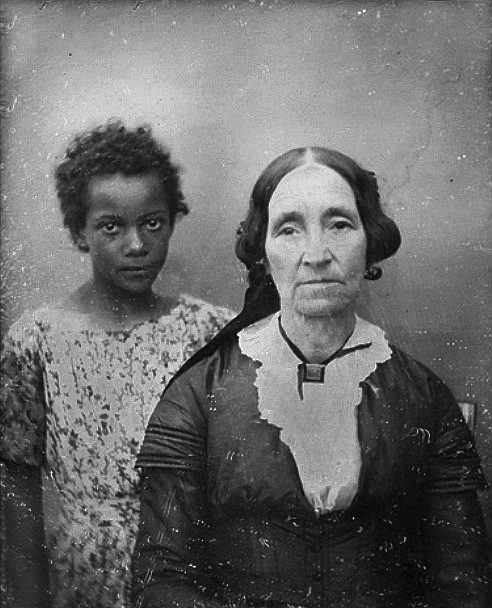

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The petition put forth by these sixty-five “ladies” was exceptional because of its collective nature, but the arguments and circumstances they laid bare in this document echoed those that married slave-owning women voiced in their homes and communities as well as in the individual bills of complaint they filed in nineteenth-century chancery courts throughout the South. In the not-so-private conversations at home and in their petitions, married slave-owning women throughout the South repeatedly made it clear that their husbands were robbing them of their slaves, squandering their assets, and violating what these women believed to be their property rights in enslaved people.

They explained how they came to own the slaves in question—i.e. whether they were inherited, given as gifts, or purchased—as well as the kind of control they exercised over them. They provided documents such as bills of sale, wills, and deeds to support their claims. With striking candor, they informed family, friends, and judges alike that their husbands came to their marriages impoverished and slave-less. It was women, they argued, who owned the slaves in their households, not their husbands. And when it was necessary, they produced witnesses whose testimony substantiated their assertions. One by one, at home and in court, married slave-owning women throughout the South did what the sixty-five women from Fayette County, Tennessee did collectively; they called upon family, friends, and judges throughout the region to help to secure their ownership of slaves and shield their property from their husbands’ ineptitude and misuse.

Source: The Burns Archive via Wikimedia Commons.

White slave-owning women were not the only ones to insist on their profound economic investments in the institution of slavery; the enslaved people they owned and white members of southern communities did too. The testimony of formerly enslaved people and other narrative sources, legal documents, and financial records dramatically reshape current understandings of white women’s economic relationships to slavery, situating those relationships firmly at the center of nineteenth-century America’s most significant and devastating system of economic exchange. These sources reveal that white parents raised their daughters with particular expectations related to owning slaves and taught them how to be effective slave masters. These lessons played a formative role in how white women conceptualized their personal relationships to human property, imagined the powers that they would possess once they became slave owners in their own right, and shaped their techniques of slave control.

These lifelong processes of indoctrination make it clear why some white women did not feel compelled to relinquish control over their slaves to their spouses once they married, why they sought to manage and “master” their slaves, why they felt completely comfortable buying and selling enslaved people, and why they sued their husbands in court over their slaves, too. The ownership of slaves was gendered: white women slave owners played roles in the trans-regional domestic slave trade and nineteenth-century slave markets. They responded to the Civil War and adapted to its economic aftermath in ways that were often different from their husbands, fathers, and brothers.

The Petition of Ladies of Fayette County, Tennessee, November 9, 1849, is Document Number: 19-1849-1, Legislative Petitions, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, Tennessee, Accession #: 11484907 Race and Slavery Petitions Project, Series 2, County Court Petitions.

Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers was a Harrington Fellow at The University of Texas at Austin from 2018 to 2019. She is the author of They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South.

—

Books for Further Reading

Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (1999) is the most recent and comprehensive study of southern slave markets to date. Johnson examines the interplay between white sellers, buyers, and enslaved people within the context of the slave market and the interstate slave trade.

Steven Deyle, Carry Me Back: The Domestic Slave Trade in American Life (2007) complements Johnson’s study by exploring the ways in which the slave market permeated every town, city, and rural landscape. By doing so, Deyle makes visible how the indifferent calculations of white southerners and the trauma that these calculations brought about in the lives of enslaved people occurred far beyond the slave market and often via private sales between members of southern communities.

Edward Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (2016) lays bare the human impact and toll of the slave trade and how the forced migration and labor of enslaved people in the West and Lower South, and the violence white southerners perpetrated against them in order to get them to do that work, proved fundamental to American capitalism.

Daina Ramey Berry, The Price for their Pound of Flesh: The Value of the Enslaved, from Womb to Grave, in the Building of a Nation (2017) studies the actual human cost of slavery via the prices affixed and values assigned to enslaved people from conception to after death. Ramey Berry’s study also reveals that enslaved people developed their own systems of value that forthrightly challenged those imposed upon them.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.