According to the infamous seventeenth-century gossip, Madame de Sévigné, on April 24, 1671 François Vatel, distraught over the late arrival of fish for a banquet in honor of Louis XIV, committed suicide by impaling himself through the heart with a sword. Sévigné and other nobles speculated that Vatel, a well-known perfectionist, succumbed to the overwhelming pressures of planning an extravagant three-day banquet in honor of the king’s royal visit and decided to kill himself instead of having to face public humiliation for his failure.

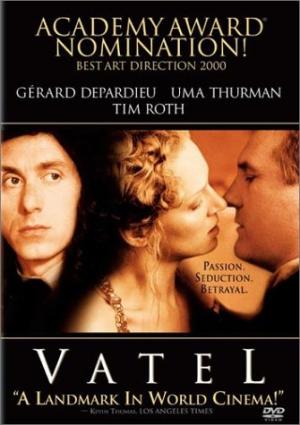

Roland Joffé’s 2000 film, Vatel, is a reinterpretation of Vatel’s (Gérard Depardieu) death, portraying him as a victim of the rigid social politics that ruled seventeenth-century French noble society. In 1671 the Marquis de Lauzun (Tim Roth) delivers a message from Louis XIV to the Prince de Condé (Julien Glover) that the king wishes to spend three days at Condé’s chateau, Chantilly. Hoping to use this opportunity to raise his social standing, the Prince de Condé orders his “Master of Festivities and Pleasures,” François Vatel, to organize a lavish affair to impress the king and secure Condé a position as general in the upcoming military campaign against the Dutch Republic.

The film chronicles Vatel’s intense drive to create innovative and delicious meals, sumptuously decorated quarters, and beautiful performances including a water and fireworks show that will be used as the event’s grand finale for the king and the 2,000 other guests expected at the banquet. Despite Vatel’s meticulous plans, when the first day actually arrives mishaps abound. To complicate matters further, Vatel becomes enamored with Anne de Montausier (Uma Thurman), a beautiful women presumed to be Louis XIV’s new lover. Disaster after disaster occurs throughout the three-day festivities, with Vatel becoming increasingly disillusioned with the prodigal nobility, leading to his suicide.

Vatel illuminates the complexity of the early modern patronage system. A hierarchy existed, in which patrons were often clients themselves. In this case the Prince de Condé’s was both Vatel’s patron and the King’s client. The patronage system was so deeply embedded in the minds of early modern people that, as Vatel demonstrates, one misstep resulting in the loss of a patron’s favor could mean social (and even actual) death. Clients worked solely to serve their patrons, knowing that their livelihood depended on their patron’s benevolence. In Vatel, that service involved a luxurious, spectacle of sensory pleasures, the very decadence of which highlighted the costs of failure.

If you are a gourmand this movie will have you salivating within ten minutes. Not only do you learn the origins of whipped cream, aptly called “chantilly” in French, but the many palatable dishes created by Vatel play a prominent role in the film. Additionally, the film is a visual feast for the eyes. Shot primarily on location at the Château de Chantilly in France, the setting is authentic and beautifully presented. While some of the vividly colored costumes and synthetic hairpieces are not necessarily unique to the seventeenth-century, overall the costumes, jewelry, coiffures, and other accessories work together to portray the luxurious ambiance that surrounded the king and his nobility. For anyone interested in the lavish, extravagant, and decadent French nobility of the seventeenth century, this is a must see movie.

For more on the history of French cuisine, you can read Susan Pinkard’s, A Revolution in Taste: The Rise of French Cuisine, 1650-1789 (2008)

A wonderful children’s book, called A Medieval Feast, by Aliki, details the extraordinary lengths the nobility were expected to go to entertain the French king when he decided to come for a visit. Delightful illustrations depict social and cultural events with considerable historical accuracy (though for a somewhat earlier period).

The Splendid Century: Life in the France of Louis XIV by W.H. Lewis (1997) discusses social life under Louis XIV.

In The Fabrication of Louis XIV (1994), Peter Burke explores the ways Louis XIV was represented in painting and other images to show how the Sun King consciously managed his public image and invented a new image of the king.

See also our READ section for Julia Gossard’s recommendation of a book about this period that treats some of the same issues as this film, A Tale of Two Murders.

By

By