When most of us think of the Renaissance, we usually imagine the rebirth of classical culture, bringing to images of spectacular paintings, life-like sculptures, and breathtaking architecture. We seldom reflect on the painstaking and often very dusty work required to bring ancient culture to life. In sixteenth-century Europe, gaining access to the cultural treasures of ancient Greece and Rome demanded effort and skill. There was no modern archaeology. Inscriptions and physical relics of the ancient world (especially those from Greece, which was occupied by the Ottoman Empire) were largely unavailable. And even the manuscripts of ancient authors were rarely ancient themselves; they were often produced centuries after classical authors like Herodotus or Thucydides originally penned their works.

As a result, recovering the culture of Greece and Rome took a lot of work. One of the most impressive projects of this recovery – and one that has received almost no attention from modern scholars – was a century-long project of reconstructing the ancient Athenian legal system. From 1546 to about 1640, nearly twenty lengthy books appeared on the subject. During that century, Greek law attracted the attention of nearly every eminent Greek scholar in Europe, including Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560), Julius Justus Scaliger (1540-1609), and Claudius Salmasius (1588-1653). Even the famous Paris printer Henricus Stephanus (1528-1598) intended to write a book on the subject, although he never followed through on his plans. Stephanus was such a crucial figure in Renaissance Greek scholarship that his system of citing Plato’s works is still used today, four centuries after his death. Virtually every important figure in Greek studies wanted to try their hand at piecing together the Athenian law.

Samuel Petit, Leges Atticae (The Attic Laws). (Paris, 1635).

What made the study of Greek law such an intellectual challenge? Couldn’t these scholars just look at ancient Athenian lawbooks, do a bit of rearranging, and produce a fancy new edition of the Attic laws? Not exactly. Scholars were able to do this sort of thing with Roman law, which had survived antiquity in four massive volumes compiled under the emperor Justinian (r.527-565 CE) in the late sixth century. Renaissance Roman lawyers faced their own unique challenges like restoring corrupted text and interpreting archaic Latin terms. For example, one of the first and most important tasks of jurists such as François Hotman (1524-1590) was detecting the ways in which Justinian’s editors had changed the original Roman text and restoring the Roman laws to their original wording. Work of this sort abounded, but Roman lawyers held a critical advantage: they possessed four imposing volumes of Justinianic laws, providing a clear foundation for studying their subject.

Athenian law, on the other hand, was a blank spot on the map. No compilations of ancient Athenian law survived from antiquity. As far as we know, the Athenians themselves never created systematic legal texts to organize their own laws. If you asked even the most educated European scholar in 1500 what the contents of Athenian law were, they might be able to vaguely point to a legal citation from Demosthenes or another Greek orator. But there was no comprehensive body of knowledge about the content or procedure of Greek law. In a culture that was obsessed with recovering ancient culture, this was a massive gap in knowledge.

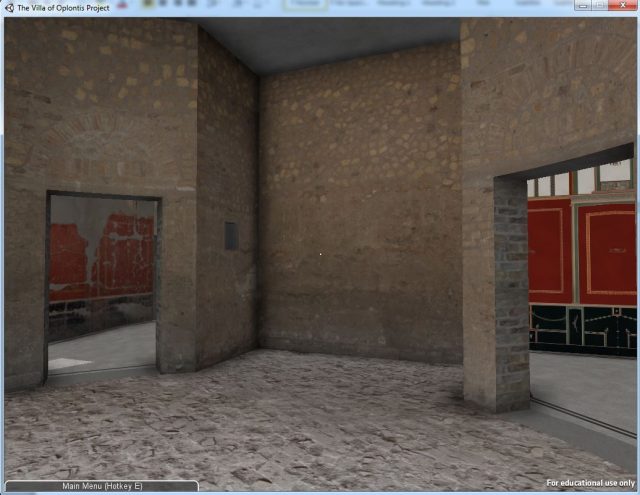

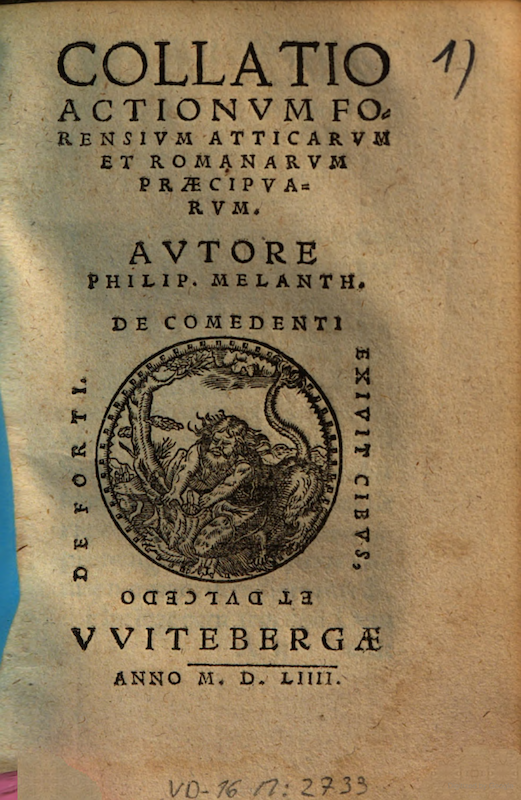

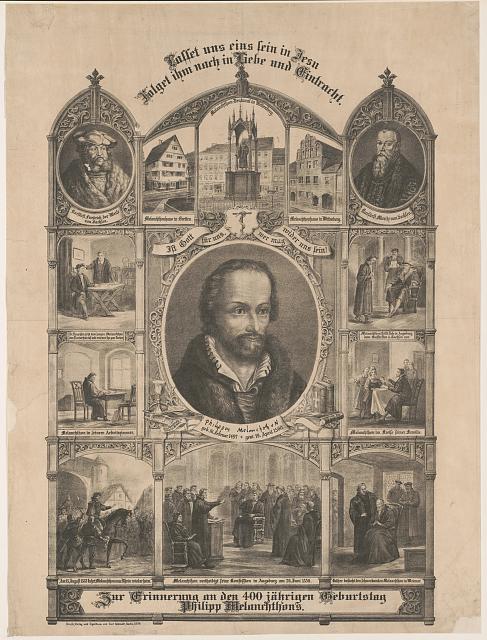

As a result, reconstructing Athenian law was a project with no obvious starting point. There was no central text to work from; hints and clues about the laws of Athens were scattered across ancient literature. For this reason, piecing together Greek laws required sustained detective work. Take, for example, Philip Melanchthon, the German Lutheran reformer and the first scholar to attempt to reconstruct them. By 1546, when Melanchthon published his work entitled “A Comparison of the Chief Attic and Roman Legal Actions”, Melanchthon had taught Greek literature at the university of Wittenberg for nearly two decades. He had translated, lectured on, or written commentaries on nearly every imaginable Greek author, including famous writers like Homer and Euripides as well as lesser-known figures like Theognis. This broad experience allowed Melanchthon to draw from an encyclopedic knowledge of Greek literature as he embarked on the first attempt to reconstruct the various trials and procedures of the Attic legal system.

Source: Library of Congress

Greek orators like Demosthenes were particularly important for this project of reconstruction. Since most surviving Greek speeches are actually legal speeches which were given at trial, they contained a wealth of information about law, including details about legal procedures and the roles of witnesses and judges. When scholars like Melanchthon got especially fortunate, they could even find quotations of entire laws buried within the speeches. Similarly, historians like Xenophon and geographers like Pausanias often contained offhanded remarks mentioning specific laws. Drama, too, was an important source, since Greek plays often included characters getting into various kinds of legal trouble. It is worth highlighting how advanced these Renaissance scholars were in their method. Twenty-first century scholars of Attic law draw from these same basic sources, although they now incorporate evidence from newly discovered inscriptions and a much deeper knowledge of the ancient Greek world. The Renaissance approach prefigured the one that is still used in universities today.

The haphazard and scattered nature of these sources underscores that this recovery of Athenian law was a magnificent achievement of Renaissance intellectual life. After the publication of Melanchthon’s text, a stream of works appeared that deepened the European understanding of the ancient Greek law. In 1559, the French lawyer Pardoux Duprat published a work reconstructing the laws of the ancient Athenian legislators Solon and Draco. In 1593, the Danish historian Niels Krag even expanded the scope of inquiry beyond Athens and uncovered the laws of ancient Sparta in his De republica Lacedaemoniorum (On the Spartan Republic). In 1635, the English jurist Samuel Petit produced the capstone of Athenian legal history in the form of his monumental Leges Atticae (The Attic Laws), which was still cited well into the nineteenth century.

But what, exactly, was the point of all this? Were these scholars just aloof antiquarians? The surprising but critical fact is that Greek law actually came to feature in some of the most contentious intellectual debates of the day. Attic law became an important way to think about the relationship between law and religion. For example, Melanchthon had arranged the Attic legal actions in parallel with the Roman ones and then organized them under the headings of the Ten Commandments. Under the commandment “Thou shalt not kill”, Melanchthon included all the Attic and Roman actions against assault and murder. As the introduction to the clearly indicates, Melanchthon saw the Attic law as proof that God’s law – the Ten Commandments – had been valid even for the ancient pagan nations. For Melanchthon, Greek law confirmed the universality of biblical morals.

Scholars drew upon Greek law for a variety of other uses. In his 1564 work, De Republica Atheniensium (On the Athenian Republic), the Italian historian Carlo Sigonio illustrated how law fit into the broader context of ancient Athens, providing one of the first holistic accounts of ancient Athenian society. The Danish historian Niels Krag held up the Spartan laws as a rebuke to European customs. In particular, he used Spartan laws about crime and punishment to highlight the barbarity of the European practice of displaying the bodies of those who were publicly executed. Greek law also became a part of contentious political and economic debates. The recovery of the ancient commercial laws of the Greek city-state of Rhodes set off a series of controversies about maritime law and free trade, something I write about at length in my upcoming monograph project. And in the 1640s, Athenian laws about monetary loans took center stage in important debates between French scholars Claudius Salmasius and Desiderius Herauldus over whether Christians could charge interest. Significantly, the seventeenth-century debates which overturned the medieval consensus against interest contained heated arguments about Attic law.

Recovering Greek law was a tremendous accomplishment. But it was also emblematic of a new way of doing history. The majority of Renaissance readers perused ancient texts for lessons about morality or models for eloquence and poetics. The scholars discussed above did not do that. They looked to ancient texts for submerged knowledge about the ancient world. They read orators like Demosthenes not for lessons on style and persuasion, but for information about how the ancient Greeks handled their differences in court. These scholars looked at ancient literature as a mass of clues about the ancient world, and they approached it as detectives. Perhaps more accurately, they approached it as modern historians. In other words, the recovery of Greek law was one of the first major accomplishments of modern history writing.

Alexander Batson received his PhD in History from Yale University in 2024. He is an intellectual and legal historian of early modern Europe. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in the Journal of the History of International Law, Reformation & Renaissance Review, Grotiana, and the Journal of the History of Ideas. Alexander is a postdoc at the School of Civic Leadership at UT Austin.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Banner picture: Photo by Josiah Lewis: https://www.pexels.com/photo/stonewall-palace-772689/