NEP’S Archive Chronicles explores the role archives play in historical research, offering insight into the process of conducting archival work and research. Each installment will offer a unique perspective on the treasures and challenges researchers encounter in archives around the world. NEP’s Archive Chronicles is intended to be both a practical guide and a space for reflection, showcasing contributors’ experiences with archival research. In ‘Unexpected Archives’ Michaela Feinberg writes about the Cahiers William Ponty, a collection of school book assignments produced by students in the early 20th century, through which she studies dance and performance art in Senegal.

I arrived at the Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire (IFAN) in Dakar, Senegal in December of 2023, six months into my dissertation research on the history of theater and dance in Senegal. My project explores theater and dance performance in Senegal under colonial rule and marks the ways that African artists creatively navigated and pushed the boundaries of a restrictive colonial system. I had spent my time in Senegal’s national archive tracing the development of dance and theater troupes in the 1950s and 60s. This line of inquiry brought me to an unexpected place – the École Normale William Ponty, which was a colonial all-boys school that educated a new African elite located in Sebikotane, Senegal. The school’s students would go on to become politicians, scholars, and artists; its alumni include Ivoirian president Félix Houphouet Boigny and renowned Guinean choreographer Keita Fodeba. Beginning in 1933, Ponty students began writing and performing plays that creatively rendered African histories and stories, combining dance, music, and dramaturgy. These early playwrights would coin a new genre of performance, théâtre africain d’expression française (African theater of French expression) whose influence would reach into the present.

The school was founded in 1903 in Senegal and aimed to prepare students for careers in colonial administration, teaching, or medicine. The school’s curriculum highlighted colonial anxieties about creating an elite class of Africans that was too alienated from their cultures to properly lead their communities and fulfill the colonial mission. To that end, Ponty students undertook assignmentsthat encouraged students to investigate their histories and cultures and discern values that could be developed in concert with the colonial project.

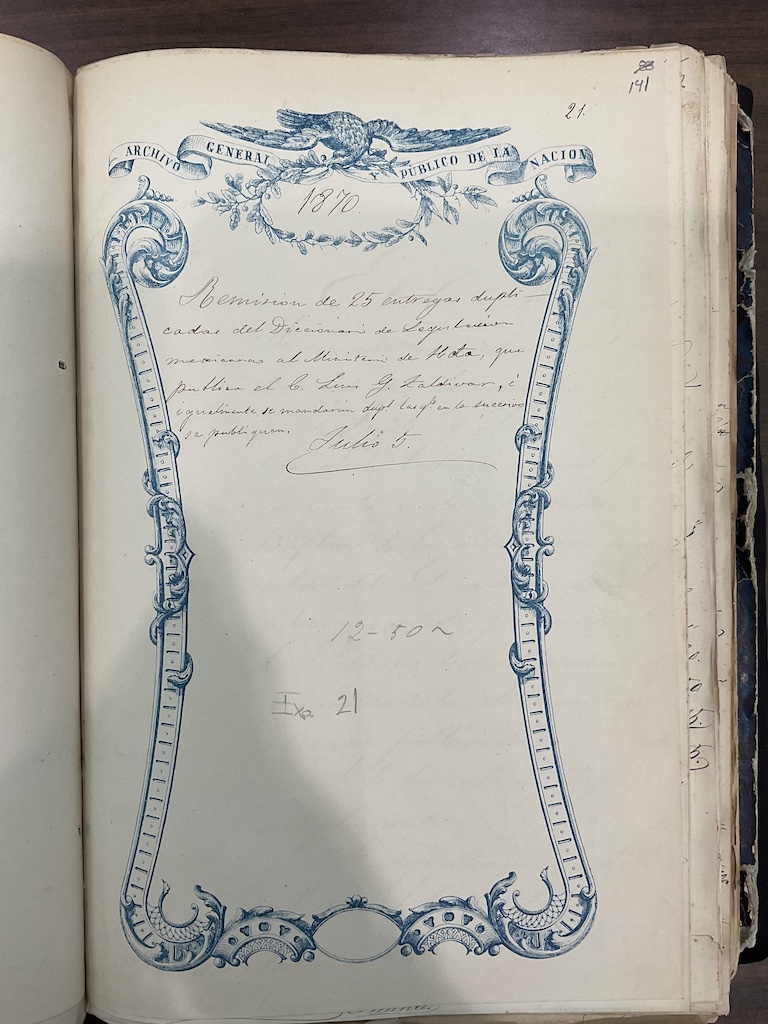

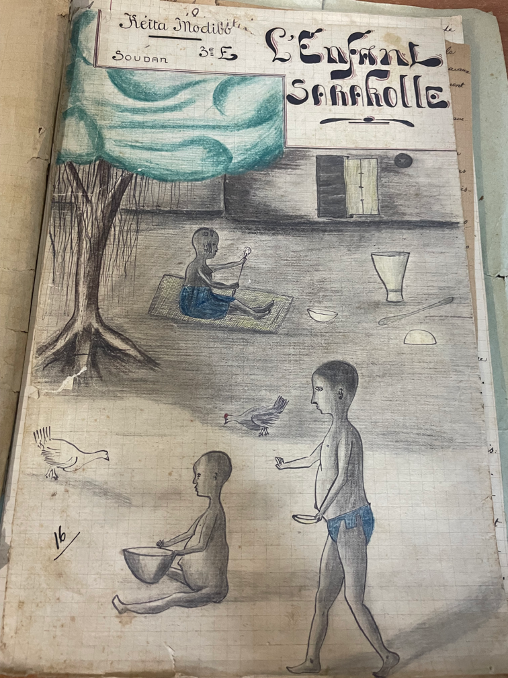

I visited IFAN to access one very specific collection in its library – the cahiers (or notebooks) that students produced each summer. When I began studying theater and dance, the last thing I expected to be doing was reading the summer assignments of the Ponty students. At the same time students began to write plays, they undertook a separate but (I suggest) interconnected assignment in the summer of their third year. As part of their final grade, they were asked to return home to their villages and produce cahiers (notebooks) on topics like cuisine, dreams, and music. These cahiers can be as long as 75 pages, all handwritten and beautifully illustrated. Students were clearly trained in ethnography and art and meticulously rendered images and descriptions of daily life. They were asked to be translators (often literally) of their cultures and experiences and make these things palatable and legible to their French instructors.

The library of IFAN holds hundreds of these cahiers in a discrete collection. The library collection doesn’t include other documents from the school which compelled me to spend all my time and energy into these assignments. When I arrived, I wasn’t sure if or how these cahiers would tie into my work on theater and dance. Was there a connection between the cahiers and the plays students were writing? What could I learn about dance and performance from these documents?

IFAN is located on Dakar’s scenic corniche in the Université Cheikh Anta Diop, just a 20 minute oceanside walk from my Fann Hock apartment. On its south facing wall is a large mural of renowned historian and politician Cheikh Anta Diop that looks as if it has been chiseled into the side of the building. The building houses three divisions – a library, the IFAN archive, and the audiovisual archive. I arrived there at a difficult moment – the university had been shut down for over a semester after political protests rocked the country in June 2023. Then-president Macky Sall had launched an increasingly desperate and violent bids for an unconstitutional third term, igniting protests throughout the country. IFAN was mostly empty when I arrived along with a colleague, and a sign on the library door read CLOSED in red marker. The archivist I met with initially was relieved we’d be in Dakar long term since receiving permission to access the archives could take weeks.

I wrote three letters each to the director of IFAN requesting access to each department and handed them in to the building’s mailroom when the director proved elusive. Unlike Senegal’s national archive which doesn’t require special permission, my letter had to make its way through IFAN’s bureaucracy before being approved and forwarded to myself and the archivists. Two weeks later, I received separate emails that put me in contact with archivists in each department and indicated I had permission to access the collections.

When I arrived at the library on the ground floor of IFAN, I was the only researcher there. I met with the archivist who quickly revealed himself to be a dance enthusiast, and I had many conversations in the next few months about my research and the documents I was looking at. Like me, he was unsure of how exactly the cahiers would be relevant to my project but brought me a finding aid and pointed me towards the notebooks on art and music. After signing up for a library card, I was given a thick stack of papers that listed every cahier by student name. The number of topics that students wrote on was overwhelming. I quickly decided that trying to read a large volume of cahiers was unrealistic and chose a smaller subset to home in on. The prompts of “musical instruments,” “African literature,” and “indigenous arts” seemed the most promising.

The first cahier I requested was titled Instruments de musique by Baba Male, a student from Koutiala, Mali (then French Soudan). The notebook was covered in newspaper with World War II headlines: The Allied air offensive; Allied raids on Austria; The total occupation of Cassino is only a matter of hours away! On the title page was a full color drawing of a jaunty chasseur (hunter) performing a hunting dance with a rifle in hand. He has a cigarette in his mouth and a small smile as he looks out at the reader. His yellow pointed shoe is poised to step forward and his blue boubou flows around him. He is accompanied by three drummers (whose drums Male will go on to diagram later) and a group of women clapping along. The scene is saturated in purples, oranges, blues, and yellows. Throughout the notebook, Male meticulously diagrams each musical instrument, allowing me to return to this illustration and recognize each drum.

Photography is not allowed at all in the archive, so the process of transcribing these documents is long and often difficult. But it feels fitting, like an acknowledgement of the work that these students put into their assignments. Attending to every word, image, and subheading rather than simply photographing the whole document and moving on is meditative. That first day, I was so captivated by the image of the dancer that I made a (poor) sketch in my own notes in the hopes of capturing the sense of movement and directionality the student was able to create. I wanted to remember the sense of motion and emotion of the image and be able to describe it accurately in my writing. Deciphering the looped cursive (which often became difficult to read towards the end of the cahiers) made me acutely aware of how much time and effort had gone into this assignment.

“Reading” dance in the archive is a challenging task, especially since colonial descriptions fall into racist tropes, describing “frenetic” and “primitive” movement and flattening and distinction between different dance techniques. Male’s illustration gives us a very different and much more detailed rendition. However, this kind of diagramming and categorization is also fraught. As I accessed the collection, I became hyperaware of how these cahiers could be an often-disturbing window into how young students were asked to strategically devalue their cultures. Male praises the colonial project and lauds the French for their investment in “progressing” African art. This kind of evolutionist rhetoric permeates these documents. I found that there was a constant tension between the care students demonstrated when diagramming their cultures and the formulaic regurgitation of colonialist thinking. What are the possibilities and limits of these assignments? What did it mean for these young people to stand at the junction of colonial and African society and act as mediators of information? Are these documents simply performances of colonial ideologies? I am still thinking through these questions as I write my dissertation, but ultimately, I don’t think so. I think that the cahiers are intimate and creative evidence of students grappling with their new roles in the colonial order.

What started as an experimental foray into the archives of the Ponty school in the end completely changed the trajectory of my dissertation project. I returned to IFAN in February of this year to continue my work with this collection. The university is no longer deserted, and the library is full of students and researchers. It is easy to be overwhelmed by the scale of this archival collection. I hope that, by zooming into a small selection of cahiers, I can highlight the details and take seriously the ways that these students were proposing an enacting a new artistic practice, one that would reverberate for decades to come.

Michaela is a PhD candidate at Yale University. Her dissertation explores the politics of Senegalese dance and theater from the colonial period to independence. Her work synthesizes diverse archival sources, including plays, performance programs, and colonial administrative documents.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.