What happens when historians take a pause from using archives to write history and instead delve into the science of producing digital archives? If you are a traditional historian, you might cower at the bombardment of technological know-how that comes your way. Look a little closer however, and you soon find that archival science is an intellectually and theoretically rich field. Engaging with digital archives and digital history is a great way for scholars to re-think how they and archivists alike, select, categorize, and publicize historical data for educational and scholarly purposes. As historians increase their use of digital platforms, it can be helpful for all historians to take a step in the archivists’ shoes.

In the spring of 2016, students of Dr. Virginia Garrard’s course, “History of Modern Central America through Digital Archives” had this opportunity. The course bridged traditional historiography with an introduction to digital archives and digital history. Students came from a wide array of disciplines, from Information Studies to History. For their final project, they could choose between writing a traditional research paper or designing a digital history project, or both. This mix of both worlds allowed for a hybrid conversation that melded traditional historical debates with sensitivity to the way scholars and archivists produce and organize knowledge.

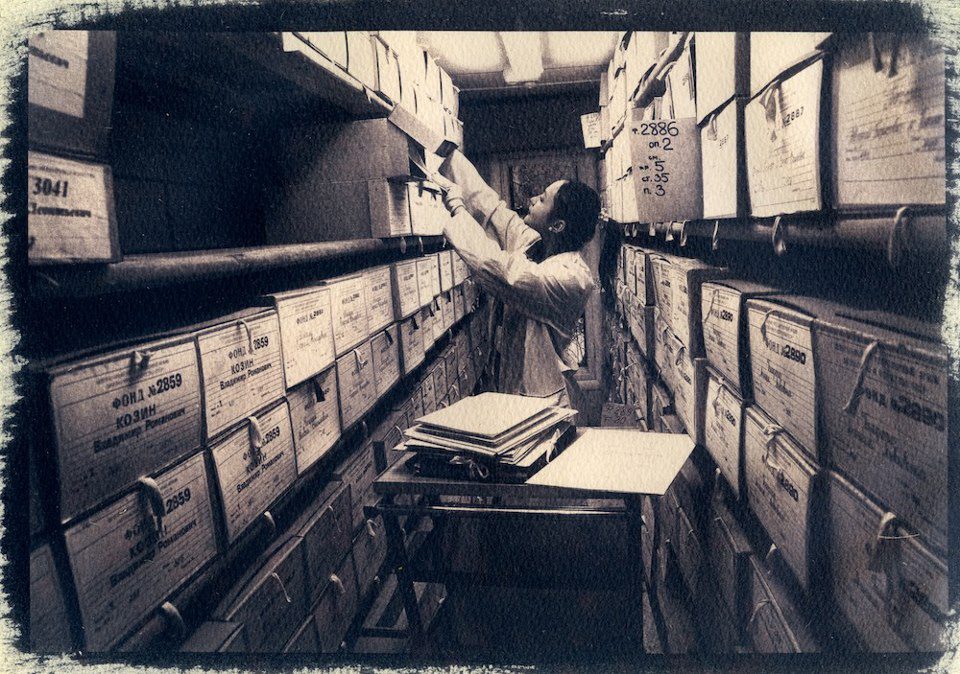

The National Library of Guatemala, a more traditional place for historians to conduct research (via Wikimedia Commons).

Students eager to get up-to-date with newer digital history platforms were not disappointed. Homework assignments ranged from digital primary source scavenger hunts to analyzing pre-established digital scholarly interfaces, such as the Latin American Digital Initiatives Collection (LADI). The class introduced students to up-to-date digital projects like interactive maps, self-correlating databases, and archival metadata. Students also worked in groups to grapple with the challenges of making digital archives more accurate and efficient.

One of these challenges involved selecting the right “subject terms” that help users search for content in digital databases. To facilitate the search process, students needed to produce terms that were neither too narrow nor too broad, and that represented the “aboutness” of their subjects. Just how efficient, accurate, and unbiased these terms appeared influenced the way users would receive and write about history. In one instance, I had to produce English subject terms for a short and vague Guatemalan newspaper about a desaparecido or forced disappearance. Choosing between terms like “assassination,” “murder,” and “homicide” prompted me to scrutinize the meaning, political implication, and contextual relevance of each term. These questions added a nuanced perspective to my research as well.

Forced disappearances were common during the Guatemalan Civil War (via YouTube).

A less somber yet strangely satisfying task involved creating a sound bite archive from Radio Venceremos—an underground anti-government radio program from 1980s El Salvador. Here, students created an archive of background noises: shouts, singing, frogs, birds chirping, gunfire, alarms, helicopters, and static. Rather than paying attention to content, they recorded language dynamics, the environment, and materiality. This innovative way of organizing data allowed them to get at more subtle information, such as timing, emotion, background events, secrecy, and level of danger. This was detective work at its finest and “tech-savvyist.”

Of course, walking away with new skills in digital media was not the be-all and end-all. Thinking more deeply about digital archives illuminated urgent theoretical questions relevant to scholars and archivists alike. To whom do historical records belong? What biases do archivists and scholars convey when presenting data? Do living (or even dead) historical actors want others to publicize information about them? How do we reconcile the desire to uncover histories, with the risks and inconveniences public knowledge poses for historical actors and their communities?

Personally, this course contributed to thinking about my dissertation on Guatemala’s recent civil war, which spanned from the 1960’s to the 1990’s. The legacy of the civil war carries over to present-day Guatemala and presents political and ethical roadblocks to the publication and presentation of records. Emerging data may appear rich for archiving, as the recent Guatemalan National Police Historical Archive demonstrated. However, historical records are living things that carry emotional, political, and economic consequences for present-day actors. As this course demonstrated, archives are anything but a mere compilation of sources. They require much human configuration, strategic organization, and logistical coordination. On the other hand, they demand sensitivity to the ethical, political, and intellectual problems of producing knowledge.

Virginia Garrard-Burnett on La Violencia in Guatemala.

John McKiernan-González tells the story of the first nationally distributed Latino-themed public radio show in the United States.

Charley Binkow discusses the online archives of the 1914 Easter Rebellion in Ireland.

![]()