NEP’S Archive Chronicles explora el papel que desempeñan los archivos en la investigación histórica, ofreciendo una visión del proceso de trabajo e investigación archivística. Cada entrega ofrecerá una perspectiva única de los tesoros y retos que los investigadores encuentran en los archivos de todo el mundo. Crónicas de archivo de NEP pretende ser tanto una guía práctica como un espacio para la reflexión, mostrando las experiencias de los colaboradores con la investigación archivística. En esta entrega de las NEP’s Archive Chronicles, publicada en inglés y español, Juan David Osorio Vargas piensa el el archivo hasta no ver, así como la ceguera y las redes afectivas

Note: Click here to access the English version.

Nota: Haz click aquí para acceder a la versión en inglés.

Jacques Derrida nos dice que existen, fundamentalmente, dos tipos de experiencias que son muy diferentes entre sí.[1] Una de ellas se establece en el presente y se refiere a aquello que podemos neutralizar con nuestros ojos. En este caso, una de las funciones del ojo es ver venir, anticiparse ante lo desconocido o ante la presencia de lo otro. Esta constituye una de las dos experiencias posibles. La otra, que quiero profundizar a continuación, es la experiencia de la ceguera. Es aquella que traza un viaje inesperado, imprevisible y abierto hacia la heterogeneidad de lo otro, ese otro que está allí para sorprendernos. Se trata, precisamente, de un viaje no programable, una cartografía de lo indeterminado, carente de finalidad. Es la experiencia del presente que nos remite a la incertidumbre de un evento histórico.

Como historiador ciego, estoy convencido de que las formas de conocimiento organizadas por otros sentidos son valiosas en sí mismas. La pregunta de si el historiador ciego puede acceder a los materiales del mundo visual tiene una respuesta afirmativa. Podemos trazar un lenguaje con estas características si ampliamos significativamente el alcance democratizador del archivo, así como las preguntas que lo rodean, mediante tecnologías de compensación que aseguren que la traducción de un registro a otro no pierda su estatus de legitimidad.

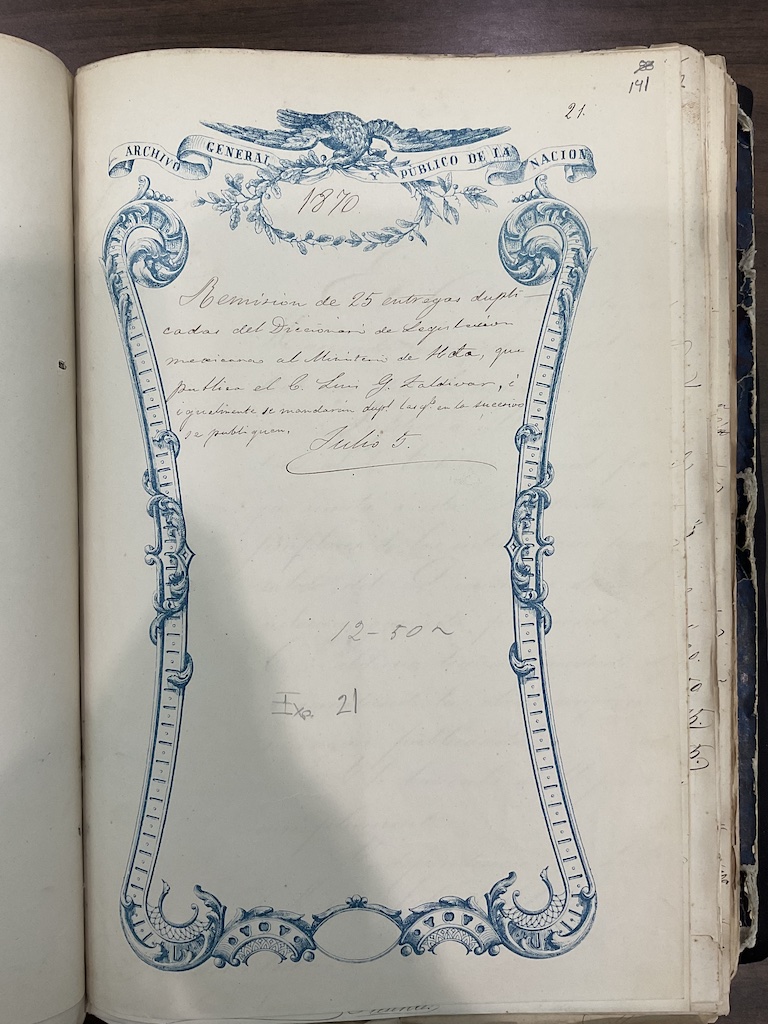

Quien se enfrenta al archivo atraviesa la experiencia de la ceguera. No todos los historiadores tienen ojos para ver venir por adelantado. El archivo nos enseña que, cada vez que entramos en él, se torna más incontenible y ajeno. Si partimos del segundo concepto de experiencia, podemos percatarnos que el archivo es un viaje sin horizonte aparente, con vista a lo que no está a la vista, una idea que se aproxima profundamente a la práctica del historiador.

El archivo es la experiencia de la ceguera porque no podemos anticiparlo. No sabemos con qué nos sorprenderá ni a través de qué nueva tecnología o pregunta nos responderá. Mucho se ha hablado del silencio de los archivos y de las borraduras que contiene, pero poco se ha reflexionado sobre la cualidad de la ceguera que habita en ellos y sobre la relación que establece con la visibilidad.

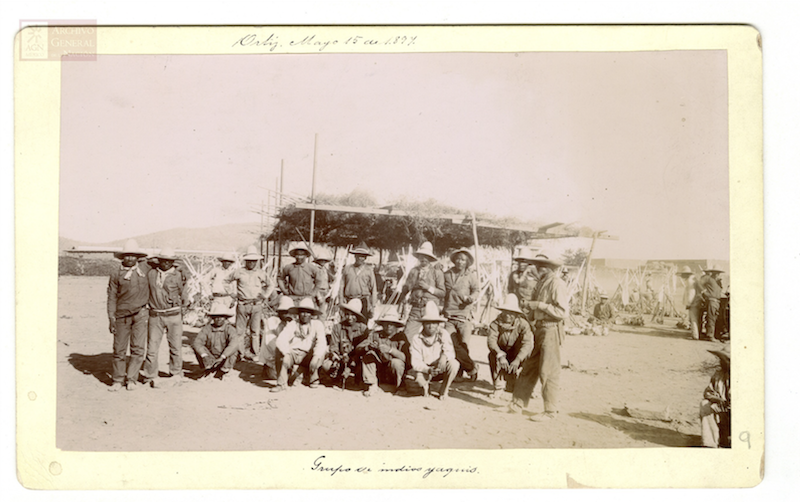

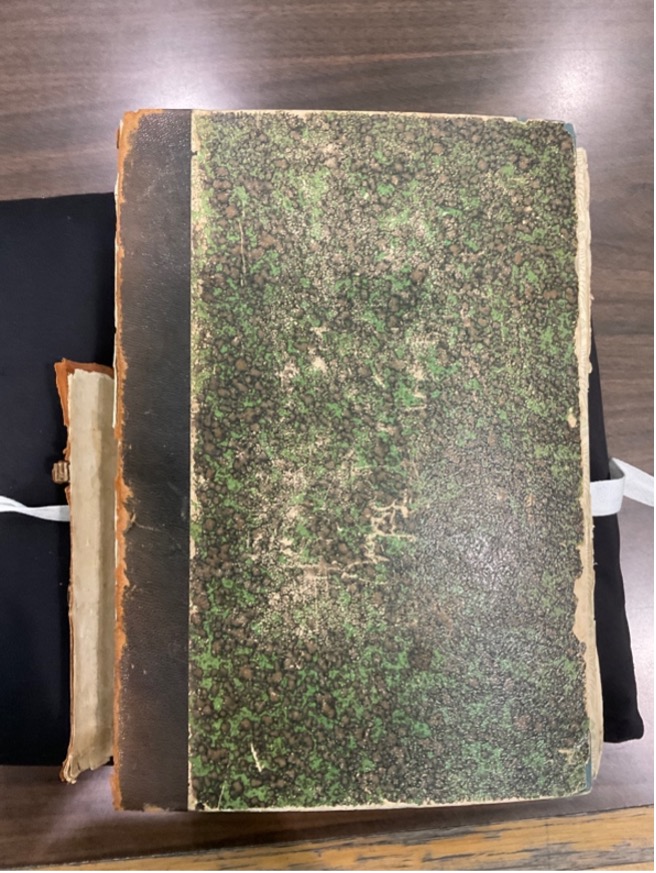

El verano pasado, mientras realizaba investigación de archivo en Colombia y Panamá, me encontré con esta realidad: no bastaba con ser ciego y vivir la doble experiencia de la ceguera para enfrentar el archivo, pues el habla también implica, estructuralmente, la no visión. Y es el habla mi primer acercamiento al archivo. Pareciera que aquellas voces familiares, que no se ven, son la realidad inmediata de su presencia. Percibo palabras que pueden interesarme. Hago una pregunta y me encuentro con el silencio. El archivo, otra vez, está mudo. Mi mamá se esfuerza por encontrar la palabra que busco en un documento que se está haciendo polvo, pero ella tampoco la ve. Nos quedamos a tientas. Estamos ciegos.

Reflexionaba sobre como esa materialidad podía actuar y hablarme para que yo pudiera interrogarla con mis indicios e intuiciones. Percibí el archivo como ese dispositivo irremediable que debemos transitar para llegar a algún lugar del pasado o del conocimiento histórico, de una manera similar a como concibo el bastón que, día a día, me permite tantear los espacios aún desconocidos que atravieso al caminar. La naturaleza de esta experiencia es la aprehensión: esa propiedad que habilita el desplazamiento entre la voz y el archivo, análoga al espaciamiento de la relación coordinada entre la mano y el bastón.

Considero que las múltiples mediaciones que permiten acceder al archivo son tecnologías que ayudan a comprender aquello que se revela. Representan una suerte de antropología muy antigua de la captura del mundo, cuya función es la de reducir la complejidad o familiarizar lo desconocido. Estas formas descargan el extrañamiento que produce la distancia temporal y la imposibilidad de leer un testimonio del pasado a través de la biología misma de los ojos. Estas tecnologías múltiples deben ser entendidas como partes constitutivas de las redes de lectura, interpretación y trabajo que ejecutan la práctica del historiador: voces que comunican sus trazos, grafos y huellas. Permitamos, entonces, que las tecnologías que circundan al archivo también hablen, rodeándolo críticamente. Son esas voces -como la de mi madre, mi padre y amigos- las que intentan hacer hablar al archivo en una red compleja de pregunta, respuesta e interpretación; un círculo hermenéutico que refuerza creativamente esta experiencia del no ver.

Más que cualquier técnica contemporánea relativa a la digitalización masiva o a la utilización de la inteligencia artificial, es la proximidad de la voz lo que pone en presencia al archivo y lo acerca a la vida tanto de quien lee como de quien escucha. La ausencia de estas mediaciones es palpable y dramáticamente evidente en nuestra arquitectura archivística. La hegemonía de la visualidad parece gobernar la práctica del historiador, reforzando de manera positiva los hechos del pasado: lo que se lee es lo que es, y lo que registra el archivo se percibe como verdad.

Para quienes no vemos, sabemos que el archivo aparece desde el momento en que se accede a cualquier institución que custodia materiales y lleva su nombre. El archivo es todo este circuito material que lo sostiene. Su inaccesibilidad es un testimonio tangible de un tiempo pasado, con sus escaleras diseñadas para ciertos cuerpos, con ubicaciones en lugares que filtran ruido, y su ambiente predominantemente visual, desde el catálogo hasta el material de consulta, en su mayoría ilegibles para quienes no están inmersos en la lógica visual.

El archivo se inspira en las afecciones que lo hacen decir algo tras la experiencia imprevisible de la ceguera. De ahí que prescindir de los ojos no impide interrogarlo y hacerlo visible. Recuperando a Derrida, esta experiencia se presenta como una paradoja de la mirada, donde emerge un desacuerdo radical. Derrida nos invita a pensar en la elección que hacemos al mirarnos al espejo: debemos elegir entre mirar el color de nuestros ojos o mirar el influjo de la mirada que vemos. Parece que el archivo nos invita a reflexionar sobre esta paradoja. Podemos limitarnos a ver lo que nos dice o trazar el influjo de su mirada para interrogarlo y juzgarlo críticamente a través de la perspectiva. En cualquiera de estas alternativas no hace falta empezar con los ojos. El archivo nos aparece desde el comienzo en completa oscuridad; solo después emerge la mirada, con toda la potencialidad del encuadre.

La paradoja de este proceso radica en que la mirada que usamos para examinar el archivo necesita, desde el principio, un punto ciego. Aquello que iluminamos debe estar rodeado de una zona de ceguera, un borde que excluye lo inteligible del resto. Esta zona de indeterminación es el desafío que enfrenta la perspectiva: la visión de la mirada que, al enmarcar, selecciona.

Lo interesante es que no se necesitan ojos para complicar y hacer hablar al archivo: la mirada es el punto de vista de la selección, un régimen sensible que organiza la relación entre el ver y el no ver, o, dicho de otro modo, la teoría que ilumina las zonas de ceguera del pasado histórico.

La historia intelectual nos ha mostrado que el pensamiento se ha construido en torno a la metáfora de la visión.[2] Estamos permeados por su carga semántica y translaticia. Lo que yo propongo, siguiendo a Derrida, es pensar en el no ver, y creo que el archivo nos permite explorar esta singularidad. La ceguera plantea un conjunto de preguntas sobre la indeterminación de la historia. Son aquellos caminos de investigación que debemos emprender sin una carta de navegación. Por eso, la brújula de nuestra configuración antropológica nos impulsa a valorar la naturaleza de la pregunta y la respuesta tentativa.

Considero que emplear la ceguera como metáfora metodológica del archivo no solo tiene implicaciones interpretativas, sino que anima una agenda de investigación que puede ser fructífera para los estudiosos del archivo. En primer lugar, nos muestra las posibilidades sensoriales de los materiales del pasado, en una suerte de interdependencia de los sentidos como formas de conocimiento: tacto, visión, escucha, olfato; en segundo lugar, nos amplía la noción de accesibilidad y los públicos destinatarios del mismo, de acuerdo a una perspectiva democratizadora; y en tercer lugar, nos permite abordar las opacidades del archivo a través de una lectura enriquecida, planteando preguntas a tientas, respuestas provisionales, e interpretaciones nuevas.

Para cualquier desciframiento del archivo debemos enfrentarnos a la paradoja de la visión y la ceguera. Precisamente, el desafío al ocularcentrismo radica en esta paradoja: vemos sin mirar, y miramos seleccionando. Lo que propongo aquí es asumir el archivo como una experiencia de ceguera. Cubrámonos los ojos para recibirlo como un evento desconocido y singular, algo que no puede anticiparse ni percibirse por adelantado. Dejemos que la experiencia de la ceguera nos brinde la posibilidad de abordar el archivo en toda su complejidad, interrogándolo con todos los sentidos a nuestra disposición. Veámoslo desde el principio como un evento impredecible, imposible de agotar de una vez y para siempre.

Juan David Osorio Vargas es politólogo e historiador. Cursa una maestría en Estudios Latinoamericanos en UT Austin. Sus intereses de investigación incluyen las historias intelectuales de América Latina, las historias de la discapacidad y la política del cuerpo.

Los puntos de vista y opiniones expresados en este artículo o vídeo son los de su autor o presentador y no reflejan necesariamente la política o los puntos de vista de los editores de Not Even Past, el Departamento de Historia de la Universidad de Texas, la Universidad de Texas en Austin o la Junta de Regentes del Sistema de la Universidad de Texas. Not Even Past es una revista de historia pública en línea y no una revista académica revisada por pares. Aunque nos esforzamos por garantizar que la información de los artículos procede de fuentes fidedignas, Not Even Past no se hace responsable de errores u omisiones.

[1] Jacques Derrida, Thinking out of Sight. Writings on the Arts of Visible. The university Chicago Press, 2021, 35-36.

[2] Martin Hay, Downcast eyes. The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century Thought French. University of California Press, 1993, 33.