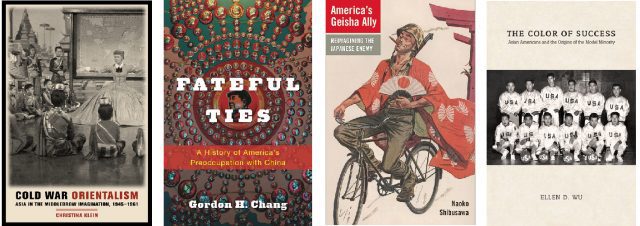

In the current era of #StopAsianHate, there have been numerous conversations regarding the unique position occupied by Asian and Asian Americans in America’s wider ethnic and racial hierarchies. Importantly, these conversations have examined the origins of the so-called the ‘model minority’ myth. Esteemed Asian American historian Madeline Hsu incisively captures that history in The Good Immigrants: How the Yellow Peril Became the Model Minority (2015). In nine well-researched chapters, Hsu walks readers chronologically through the sociopolitical processes that propelled the incorporation of a privileged class of Asian migrants and how liberal immigration policy facilitated the transition from ‘yellow peril’ to ‘model minority.’ Hsu’s overall argument emphasizes that the contemporary favorable positioning of Asian immigrants in the United States is not strictly a product of cultural traits. Instead, she points to foreign and domestic policies that prioritized the entry of highly skilled, educated, Westernized Asian immigrants.

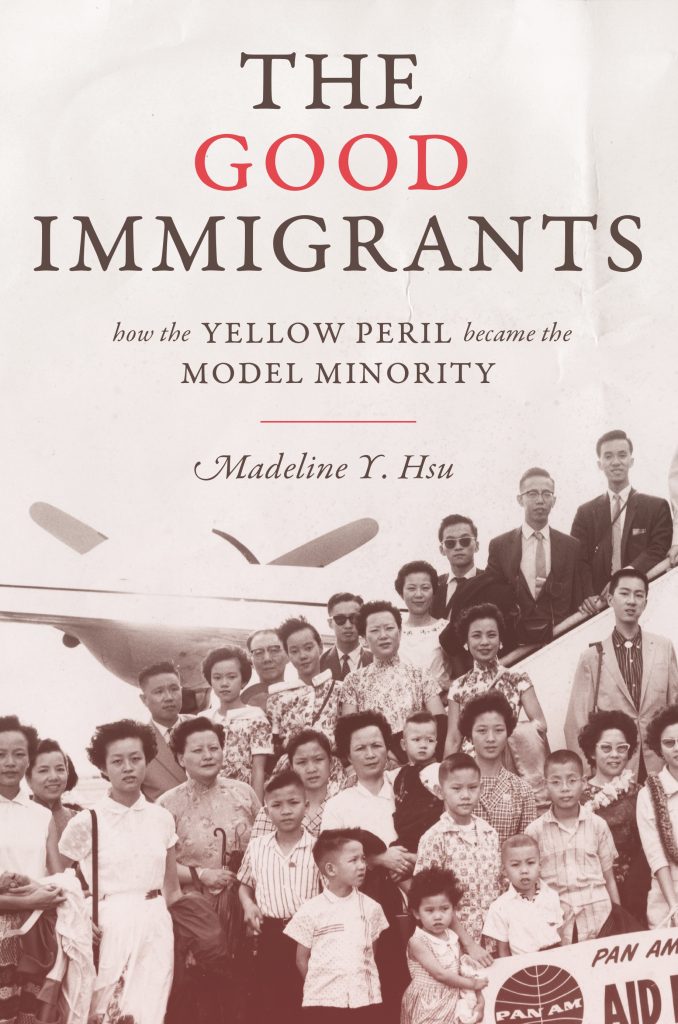

In the book’s early chapters, Hsu historically situates the entry of privileged Chinese migrants during the height of America’s racial exclusion. It is important to note that Chinese were the only group identified specifically by race for immigration exclusion. United States law prohibited Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States and obtaining naturalized citizenship. Hsu examines the contrasting experiences of the exempted classes (students, diplomats, businesspersons) of Chinese migrants who were able to enter the United States for educational purposes in what Hsu classifies as the ‘side door policy’ (36). With a special focus on exchange students, Hsu shows readers that the earliest Chinese travelers in Western countries were brought by missionaries usually as students and converts.

Chinese students were not spared xenophobic encounters and racial antagonism, but according to Hsu, they nonetheless benefited from attending American universities to foster economic development in China. Additionally, U.S. educated Chinese immigrants like Meng Zhi played an instrumental role in enhancing Sino-American partnerships by establishing cultural exchange programs like the China Institute in America to advocate for Chinese educational interests abroad. Though not explicitly stated by Hsu, the advocacy of Chinese educational interests represents early examples of transnational and diasporic politics. The political activities conducted by this privileged class of migrants laid the foundation for the elimination of America’s restrictive immigration policies in subsequent decades.

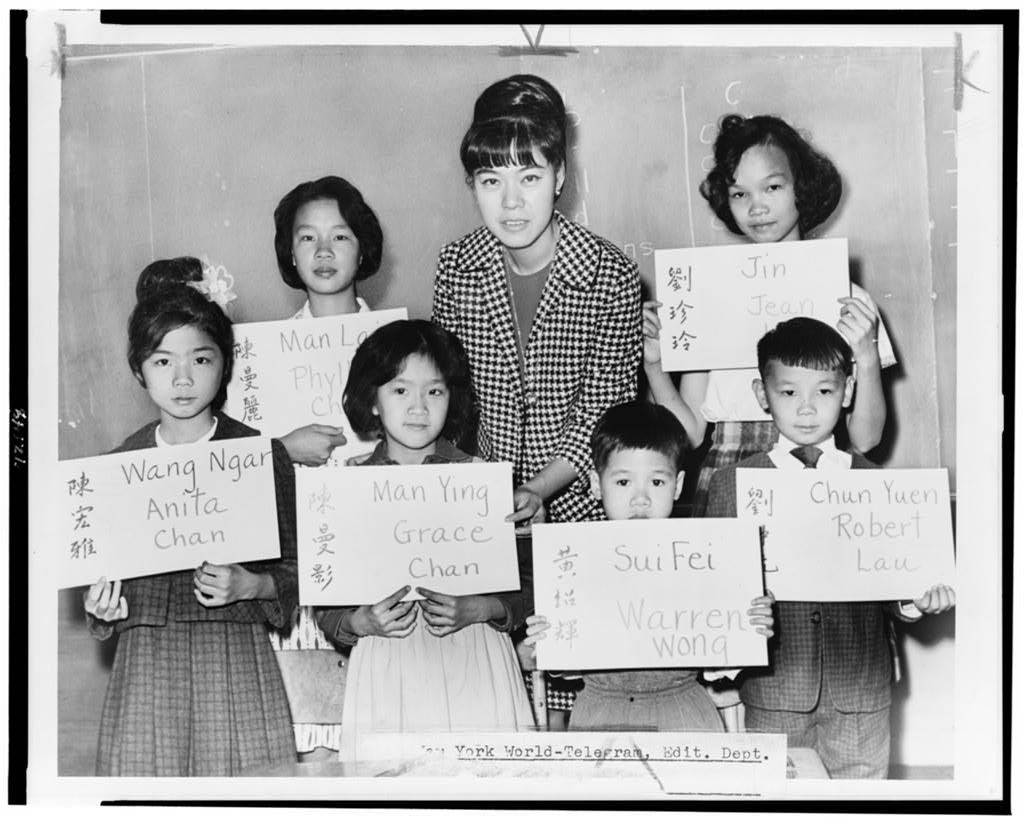

Through Chapters 4 to 7, Hsu emphasizes how Cold War politics facilitated the piecemeal but eventual elimination of America’s racially exclusionary immigration policies. During the Chinese Civil War, many Chinese students studying in the United States became stateless persons with the emergence of a communist government. This reality compelled the United States government to allow Chinese students to adjust their legal status. State and private actors began privileging the voices and experiences of educated Chinese students, who were deemed to be of economic value and assimilable because of their exceptional educational attainment and shared political ideologies with the U.S. After decades of extensive advocacy from privileged Chinese immigrants, the United States government passed the Hart-Cellar Act of 1965, which abolished racial and national origin preferences in immigration. During this period the yellow peril designation began to shift to the model minority framework. While the Hart-Cellar Act was a major milestone in U.S. immigration policy, Hsu reminds readers that the act continued to selectively screen for highly educated, highly skilled immigrants in an effort to fulfill the United States economic interests. Thus, contemporary U.S. immigration policy maintained its inherently exclusive nature and reinforced U.S. racial hierarchies.

Hsu’s concluding chapters discuss the social and cultural consequences of this new racial positioning of Asian American communities in the United States after the Hart-Cellar Act of 1965. Asian Americans, specifically Chinese American communities, became celebrated for entering professional and white-collar employment. However, Hsu reminds readers that the class status of certain Asian immigrants in the United States was due to the fact that they came from privileged backgrounds thus facilitating their middle- and upper-middle class respectability in the United States. The increased visibility of Asian immigrants in the private and public spheres is due to contemporary immigration policies screening immigrants for their economic capital and employment potential for entry.

The Good Immigrants is not only a must read but serves as an invaluable contribution to the field of Critical Race Studies because it details how different groups have different relationships with America’s ethnic and racial hierarchies. The emphasis on the perceived assimilation of Asian Americans has prevented U.S. institutions from addressing the ongoing effects of racial marginalization, which the #StopAsianHate movement examines. More importantly, The Good Immigrants shows the role post-Civil Rights neoliberal public policy has played in maintaining structural racial inequality. This book illustrates how migrants with socioeconomic status and social capital have complicated perspectives regarding American racial politics and racial inequality. While many conservatives and to some degree liberals may argue that race is no longer a factor in determining someone’s success, The Good Immigrants successfully counters popular narratives about individual responsibility and ‘cultural values’ by highlighting the structural factors that produce inequitable racial outcomes for neoliberal purposes.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Joe and his nephew Steve are searching for another Chan, their friend Chan Hung, who seems to have disappeared with $4,000 of their cash. Along the way, they encounter a gallery of Chinatown personalities and settings, revealing aspects of the district that are rarely visible to visiting tourists. They venture past the bustling restaurants and the pagoda roofs and dragon-embellished streetlights of Grant Avenue into the tight quarters of greasy commercial kitchens; the packed fish markets and grocery stores of Stockton Street; narrow, laundry-festooned residential alleyways; a local senior citizens center; and the Neighborhood Language Center offering English classes for new arrivals.

Joe and his nephew Steve are searching for another Chan, their friend Chan Hung, who seems to have disappeared with $4,000 of their cash. Along the way, they encounter a gallery of Chinatown personalities and settings, revealing aspects of the district that are rarely visible to visiting tourists. They venture past the bustling restaurants and the pagoda roofs and dragon-embellished streetlights of Grant Avenue into the tight quarters of greasy commercial kitchens; the packed fish markets and grocery stores of Stockton Street; narrow, laundry-festooned residential alleyways; a local senior citizens center; and the Neighborhood Language Center offering English classes for new arrivals.