By Thomaia Pamplin

Thomaia J. Pamplin is a graduate student at the University of Texas MD Anderson/UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences. Pamplin’s research focuses on the elderly, black community in Houston and their interactions with the healthcare system. She hopes her research will advance Narrative Medicine, a field that highlights the importance of knowing patients beyond their symptoms and causes. Pamplin aspires to be a doctor who lives up to that ideal in her own career.

Distrust in the U.S. healthcare institution has been pervasive in the black community for many generations. Although young African Americans may be far removed from atrocities like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, in which hundreds of black men were inoculated with syphilis without their informed consent and without any treatment, the mistrust seems to be handed down through subsequent generations. This lack of confidence in the healthcare system is reflected in studies that show the black infant mortality rate in the U.S. is twice as high as white infant mortality. The excess risk experienced by African-American infants reflects factors that are unique to the black experience in the U.S., including area-level poverty, differential access to pre-and perinatal care and other socioeconomic differences.[1] Studies have also shown that patients’ perceptions of their health care providers’ attitudes toward their ethnic or mental health status affect a patient’s decision to even pursue healthcare provisions.[2] Stereotypes like “the strong black woman,” also pressure women to not seek help or when seeking help, to feel as though better care is provided for non-black patients.[3]

Unidentified subject, onlookers and Dr. Walter Edmondson taking a blood test as part of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (Photo Credit: NARA, Atlanta, GA via Wikimedia Commons)

The Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis at the University of Texas reported that “Blacks of all socioeconomic levels are disproportionately affected by stress-related diseases that translate into a radicalized life expectancy.” They also found that throughout the U.S. there is a shortage of mental health professionals especially serving in low-income areas. There is a wide gap between the life expectancy of Black and White people in the U.S.; this gap “can be attributed to higher death rates among Black men and women due to heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes perinatal conditions, and homicide.” Many of these ailments are the leading causes of death for other marginalized groups in the U.S. Some of the recommendations this report makes is to expand Medicaid, health communities’ model, increase representation of black healthcare professionals, strengthen the social and economic structure of these communities, and promote health in all legislative policy.[4]

There are roughly one million practicing physicians in the US and less than 6 percent of those physicians are African-American.[5] Meaning that for the 44 million black residents of the U.S., there are about 60,000 black practicing physicians.[6] That is one black doctor for every 700 black patients. This is not to say that only African-American physicians can treat African-American patients, but distrust in healthcare institutions could potentially be alleviated by having providers be of the same ethnicity as the patient.

As the statistics of black health disparities rise and the need for healthcare intervention is increasing, the black church in the U.S. has the potential to mobilize people to seek medical care. Studies have shown that health interventions in black communities through the church have been successful, especially in early cancer detection.[7] Women play a “cornerstone” role in black churches and one study of Pastors’ perceptions on the health status of the black church and African-American communities found that “African-American women focus much of their time and energy caring for others within their church and less on their own health and well-being.” [8]

One way to understand the causes of racial health disparities, and the role of women in health care, inside and outside of black churches, is through oral histories, such as the interviews I conducted among lower-income women from a small congregation in southeast Texas. Two of their stories follow.

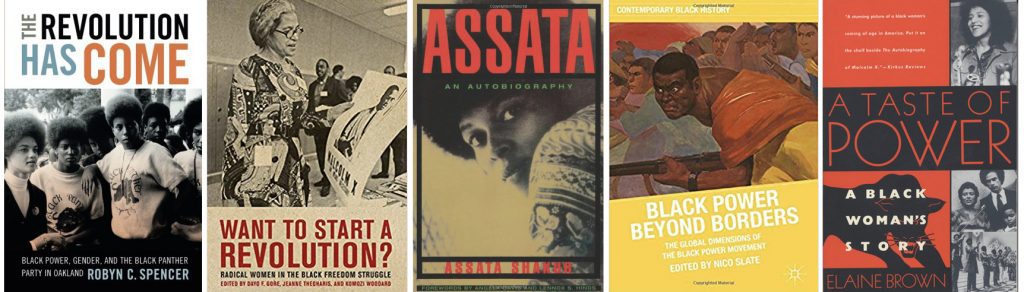

Black Nurse in North Carolina, March 1962 (via DPLA)

All Eyes on Mindi

“I remember being in school, in the classroom and not understanding what was being taught,” Mindi told me one day at a public library in South Texas. As she talked, I noticed big brown eyes peek from the edge of the wall near us. Glancing at me then, at her mom’s back, Mindi’s daughter was intimidatingly protective for a forty pound, four-year-old. Her thick, black hair was twisted in pink bow berets, somewhat resembling her mother’s short locs. The little girl skipped away after gathering the intel she needed.

“I was never bold,” Mindi told me “I was quiet and shy. And then I didn’t want to hurt people’s feelings… but now I can’t be that way anymore.”

Most of the 33-year-old mother’s career has been in education which is unsurprising when you hear her musical Texan accent. It sounds like at any point she can sing a song about a task, which would probably motivate all the kids in the library to start working.

“I would have blackouts and zone out,” Mindi continued. She had never been diagnosed with a learning disorder; however, these episodes did affect how the future educator learned. “What the teacher would say went over my head… I would have to focus ten times harder and read chapters twice over…I was always the one who needed the curve.”

In adulthood, the blackouts occurred at the worst of times, but the third incident was the most frightening. One day, while Mindi was driving her car, she had a blackout seizure and struck a pole. She didn’t drive for eight months after the accident. This incident forced her health to become her family’s top priority.

In June 2016, four months before her first seizure, Mindi’s eldest son, twelve-year-old Jay, moved out of her home and into his grandmother’s. “I was always so excited to have a family of my own, so what really caused the sickness is when I felt like I lost my son…My family was separated, my body just–” She paused, her hands were in front of her chest, the back of her hands faced me as one cupped the other. She moved her chest forward as if the words could be pulled from her, but instead, she relaxed her body, took a breath, and restarted. “He was there, but I felt like I was grieving him. I felt like I took it too hard.”

Mindi attributed the conflict she had with her son to her personality, “my son took advantage and ran with it…He would run away from home over the slightest thing. If I asked him to wash the dishes and I’m asking him for the third time, I’m not going to ask as nicely. Then bam! [He’d] run away.” She recalled how he would talk back to her but not to her husband, she didn’t believe he respected boundaries with her, but in actuality, she recalled, “those boundaries weren’t set with him, with my husband, or with my coworkers. I had to go and do that at the age of 32.”

Mindi began to see neurologists in efforts to treat her seizures. She took numerous tests, but the results would always come back normal. “I remember being hooked up to all these gears, and the physician would be doing random things to try to make me have a seizure.” He tested her as if she were epileptic, though Mindi knew that was not the case. “I just felt like based off my symptoms, he should have done different things to make me have a seizure…Rather than doing all the things by the book. I thought he should have gone outside of the box…read a little deeper into my demeanor.”

“I remember asking God to help me. I don’t want to be a victim. Deuteronomy 30:19, God says we have the power to control the mind. So, we get to choose.” Mindi internalized this idea; she would tell herself, “Mindi, you can’t be quiet and shy, speak up. If this didn’t work, then go to another doctor.” She became firmer with her physicians because her triggers were continuously overlooked by them, until finally, she met with a specialist who she felt saw her condition for what it was. “I felt like the ball was back in my court,” she said. “My best doctor is the psychiatrist that I’m seeing now. When he diagnosed me, he didn’t use all these medical terms. He put it into a form that I could understand, he explained that it was a chemical imbalance…He explained what my brain was doing and why. I wasn’t just blown off…I actually feel like I have a personal relationship with him…He wanted to see my symptoms and I was able to actually have a full-blown anxiety attack in front of him… His approach seemed more fact-based rather than assumption, that’s what I liked.”

“I have a lot of eyes on me. They’re waiting on my next move” Mindi said of her family as her daughter dashed into my view again, glancing at the both of us. According to Mindi, her increased self-advocacy has even affected the way her children communicate. “If they ever feel some type of way,” Mindi said, “they say it, and I can now give them an answer on their level to make them understand.” For her mental health, Mindi said “I can’t let anything linger. I can talk now freely…open[ly] and honest[ly] and however you receive it, I’m sorry that’s how you receive it because I have to say it for myself.”

The Treatment of Not “Very Important People”

I met with Canjie in her home in southeast Texas. Her living room had dark hardwood floors and a giant widescreen TV on the wall. The evening news was on. Canjie is a woman in her 60s. She’s tall and has a short wispy afro, along with a sweet small grin that frequently lights up her face when she greets you or laughs.

Canjie learned the importance of self-advocacy after the first time her mother became drastically ill. “She always had heart trouble,” Canjie told me. One day, about twenty-seven years ago, she called her mother from work, only to hear mother “talking out of her head,” unexpectedly she seemed mentally unwell. Canjie told her, “Momma, get ready I’m coming down there.” She drove from Houston to San Antonio, even though her mother insisted she not come. When she arrived in San Antonio, Canjie’s sister and son took her mother to see her primary care physician, a man she had been seeing for decades. “She trusted him,” Canjie remembered. Though to her family, Canjie’s mother seemed to clearly be in pain and very confused, the doctor said nothing was wrong with her. The next day, they took Canjie’s mother to see the same physician because she was increasingly unwell. Her son and the doctor argued, they “almost got into it,” Canjie said, because of the neglect her mother was receiving even after being in his care for years. Canjie remembers the older white male doctor condescendingly shaking his finger in her 24-year-old son’s face and her son angrily told him to take his finger away. Canjie’s sister had already put their mother back in the van they had come in. They had to return home quickly because a shooting had erupted in the area, “there was always some shooting going near [my sister’s] house,” where Canjie’s mother stayed.

They decided to take her to the ER, the next day “[we] found out her gall bladder was about to burst.” She remembers the ER doctor saying, “Oh yes, we’ve got to do surgery.” He also told them that their mother would not have much time to live without treatment. This incident motivated Canjie throughout her life to advocate better for herself and loved ones. “These doctors…they’ve got a lot of patients and it’s just about a job for them,” she said.

Her mother did pass away eventually, and afterwards, Canjie decided she wanted to find the doctor that had so egregiously dismissed her family. She found that he was illegally prescribing drugs to his family and other people, “so they had arrested him,” she reported. “This man was not right,” she told her family, “he didn’t give a damn about Momma. He was just making money…She made it through that, but it was a mess, I promise you that.”

Texas Hospital, 1970 (via Wikimedia Commons)

In most clinics, Canjie believed people were “being treated like cattle.” She recalled going to one’s doctor’s office, giving a few details of symptoms to a medical assistant, then only being in contact with a doctor for less than five minutes, before he diagnosed her and described her medication. She also believed that she was prescribed medication too quickly at times. “My potassium was low,” she recalled, “and right away, [my physician] wanted to write me a medication, and I said ‘No, let me see what I can do.’ So, I came home, and I started eating bananas every day. When I went back to him, my potassium was normal. I would’ve gotten that medicine for nothing.” This was 15 years ago, and she has never had a problem with potassium insufficiency since.

She does have favorable healthcare experiences, including a primary care physician, Dr. S. “What I liked about him [was] we could talk. He didn’t rush you. You know, these doctors get you and try to rush you out because they have the next patient to get [to] because of insurance [companies] and stuff. Well Dr. S, he was on that same kind of insurance, but he would sit you in his office and talk to you for 30 minutes. He didn’t rush you out… you’d have the time to ask him all kinds of questions.”

“I really loved being his patient,” she continued, “I liked his nurse. I liked the whole experience, but he decided 20 years down the road…that he wanted to do the VIP program. That’s where doctors have specific patients that pay them and have 24 hours access to them. So, they pay them not only what the insurance pays but outside of that… another $2000 a month or something of that nature,” she explained. Dr. S asked Canjie if she wanted to join the program, but she declined. “It’s for the chronically ill,” she said, “and rich [people]” she added lightheartedly, “not for me, you know?” As she said this, I searched her face for anger or disappointment, but there was no trace of resentment for not being included as a “Very Important Person” with her favorite primary care physician.

Conclusions

Mindi faced a problem that many parents and teachers experience, the weight of being responsible for many children’s upbringing. She was responsible for the development of her own children, as a Sunday-school and dance teacher, her community’s children, and as an educator, dozens in her district.

Her personality was such that her own needs and desires were not prioritized by others or herself at times. But with the intensity of her seizure condition increasing, her priorities changed. It was a very difficult road to becoming a better advocate for herself in every sphere, especially as a patient.

Mindi is typical of trends seen in black churches where their female members take on a heavy load of responsibility to others that can become detrimental to their own health. One reason Mindi wanted to share her story with me was to encourage other women with similar lifestyles, to start saying “no” more often, to take on less responsibility, and to prioritize their own health in order to live a better life.

Canjie’s experience demonstrates the difficulty of achieving good results even with advocacy. She learned to be a better advocate when her mother’s health was in danger. She used that knowledge to cut the costs of her own healthcare treatment and find physicians who she thought treated her well. Ultimately, Canjie settled for lesser healthcare experiences because her favorite physician could no longer afford to see her or anybody who could not pay the “VIP” price.

What’s at stake here is the survival of marginalized people. There is an incredibly difficult road to advocating enough for one’s self or family. The amount of advocacy needed is drastically different among different groups of people. The doubled mortality rate of black infants compared to white infants shows this. Even with evident advocacy, good treatment is still inaccessible for certain people.

There are dozens of stories like Mindi’s and Canjie’s that have been publicized and many generation’s worth of stories that have not reached the public.

This research was supported by the UT College of Liberal Arts Engaged Scholar Initiative.

References:

[1] Lauren M. Rossen, Diba Khan, and Kenneth C. Schoendorf, “Mapping Geographic Variation in Infant Mortality and Related Black–White Disparities in the US,” Epidemiology 27: 5 (2016). doi:10.1097/ede.0000000000000509

[2] Akhavan, S., Tillgren P., “Client/Patient Perceptions of Achieving Equity in Primary Health Care: A Mixed Methods Study,” International Journal of Equity Health 14:65 (2015). doi:10.1186/s12939-015-0196-5

[3] Nicolaidis, C., Timmons, V., Thomas, M.J., et al., “’You don’t go tell White people nothing’: African American women’s perspectives on the influence of violence and race on depression and depression care,” American Journal of Public Health. 100:8 (2018):1470–1476. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.161950

[4] Michelle Roundtree, “The State of Black Lives in Texas Health Report Health Report,” The University of Texas at Austin Institute for Urban Policy Research & Analysis. March 2019

[5] Kaiser Family Foundation. “Professionally Active Physicians.” https://www.kff.org/

[6] United States Census. https://www.census.gov.

[7] Slade, J.L., Holt, C.L., Bowie, J., et al. “Recruitment of African American Churches to Participate in Cancer Early Detection Interventions: A Community Perspective,” Journal of Religious Health 57:2 (2018):751–761. doi:10.1007/s10943-018-0586-2

[8] Gross, T.T., Story, C.R., Harvey, I.S., Allsopp, M., Whitt-Glover, M., “’As a Community, We Need to be More Health Conscious’: Pastors’ Perceptions on the Health Status of the Black Church and African-American Communities,” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 5:3 (2018):570–579. doi:10.1007/s40615-017-0401-x

To learn more, consider these suggestions for further reading:

“The Never-Ending Mistreatment of Black Patients” by Jessica Nutik Zitter (The New York Times)

“The State of Black Lives in Texas Health Report” by Michell A. Roundtree Ph.D., et al, March 2019

“Doctors Don’t Always Believe You When You’re a Black Woman” by Joanne Spataro (VICE)

“Black Women are Dying from a Lack of Access to Reproductive Health Services” by Lathasa D. Mayes (TIME)

“America is Failing its Black Mothers” by Amy Roeder (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health)

You might also like:

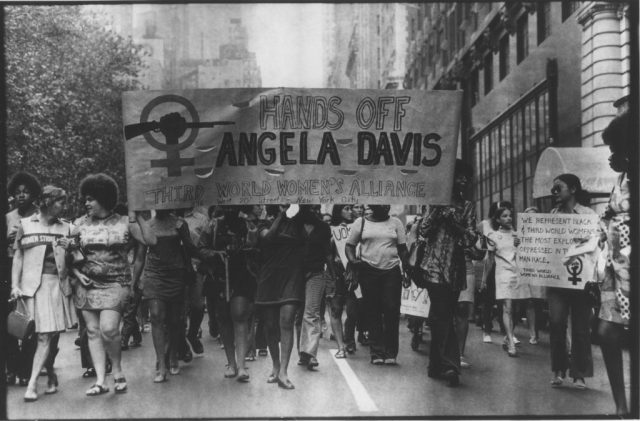

Black Women in Black Power

Episode 80: Colonial Medicine and STDs in 1920s Uganda

Contraceptive Diplomacy: Reproductive Politics and Imperial Ambitions in the United States and Japan. By Aiko Takeuchi-Demirci (2018)

Industrial Sexuality: Gender in a Small Town in Egypt

#Blacklivesmatter Till They Don’t: Slavery’s Lasting Legacy

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.