by Mark Eaker

by Mark Eaker

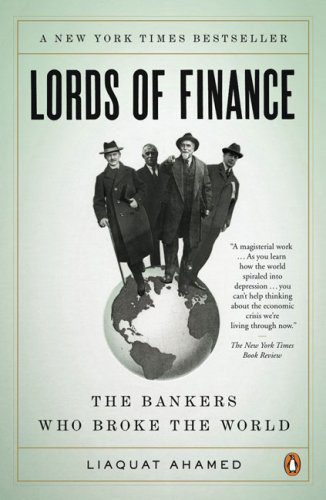

For those watching the financial markets, events in Europe are front and center. Market participants await announcements by government leaders, finance ministers, central bankers, and economists with anticipation. Depending upon the degree of optimism or pessimism generated by a given announcement, the market reaction leads to hundreds of billions of dollars lost or gained on equities, currencies, bonds and commodities from Frankfurt and London to New York and Tokyo. One might assume that the enormous worldwide impact that events in Europe are having is a function of globalization, new forms of financial engineering, and the speed of information transfer brought about by the Internet. Without doubt each of those has had an impact, but as the Liaquat Ahamed’s superb history of the events leading up to the Great Depression reminds us, it has all happened before.

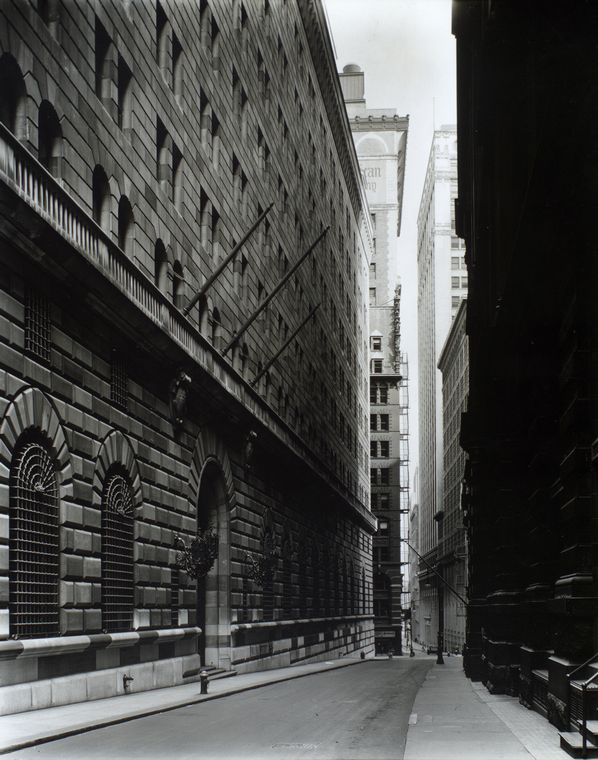

Lords of Finance is a multiple biography of the four most prominent central bankers of the 1920s: Mantagu Norman of the Bank of England; Benjamin Strong of the New York Federal Reserve Bank ; Emile Moreau of the Banque de France and Hjalmar Schacht of the Reichsbank. There is a colorful supporting cast including the economist John Maynard Keynes, Winston Churchill as Chancellor of Exchequer and Thomas Lamont of J.P. Morgan & Co. However, the focus is on the actions and inactions of the four bankers.

Ahamed did not write the book in anticipation of our reaction to the financial crisis of 2008. He does not draw direct comparisons of the events of the 1920s to those of today. His narrative is an artful description of the roles each of the men played with rich and meaningful insights about their individual characters, their relationships with one another, their ambitions, and their personal struggles. Those insights are not just bits of historical gossip but they are at the heart his explanation of the failure of the United States and Europe to confront the problems that ultimately brought about the Depression and set the stage for the rise of Hitler and Nazi Germany.

The historical and biographical details are engrossing. In addition, Ahamed’s economic and investment background allows him to deliver an excellent primer on currency, the gold standard, and international banking.

Although Ahamed does not relate the events or lessons to today’s problems, it is hard for a reader to refrain from doing so. At the root of Europe’s problem was the debt burden imposed on Germany in the form of reparations after World War I and the decisions made to return to the gold standard at pre-war rates of exchange. Today’s problems are also related to excessive external sovereign debts and a Euro currency mechanism, which, like the gold standard, eliminates devaluation as an instrument of economic policy. In the 1920s, the economic prescription was austerity and it is the same medicine being prescribed today.

Let’s hope for a better outcome and that someday another author will describe the events of our era as well as Ahamed does the 1920s.

Photo Credits:

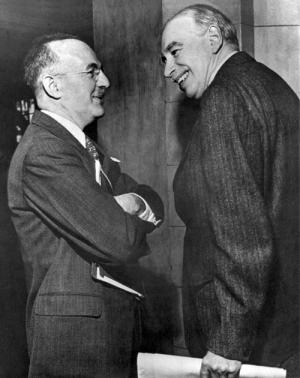

John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White at the 1946 Bretton Woods Conference (Photo courtesy of Wikipedia Commons)

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 1936 (Photo Courtesy of The New York Public Library. Photography Collection: Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs)

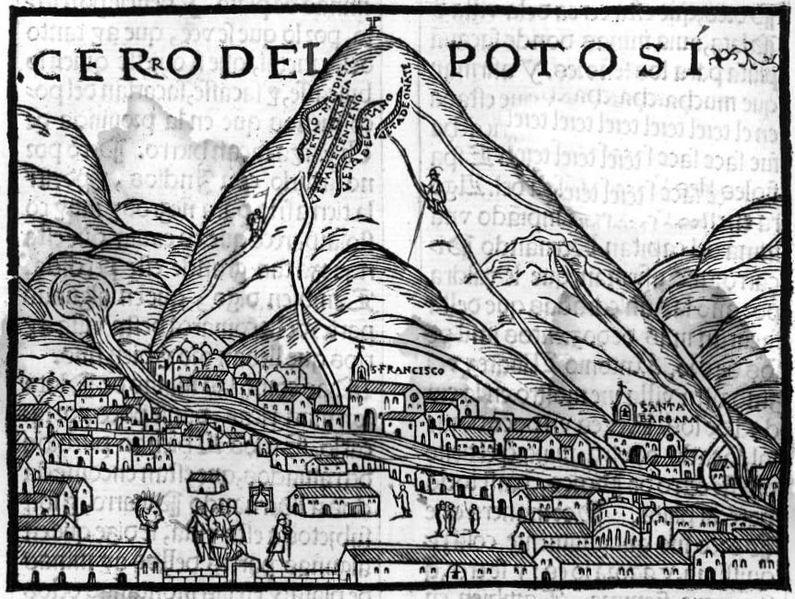

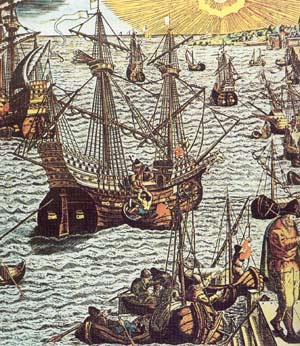

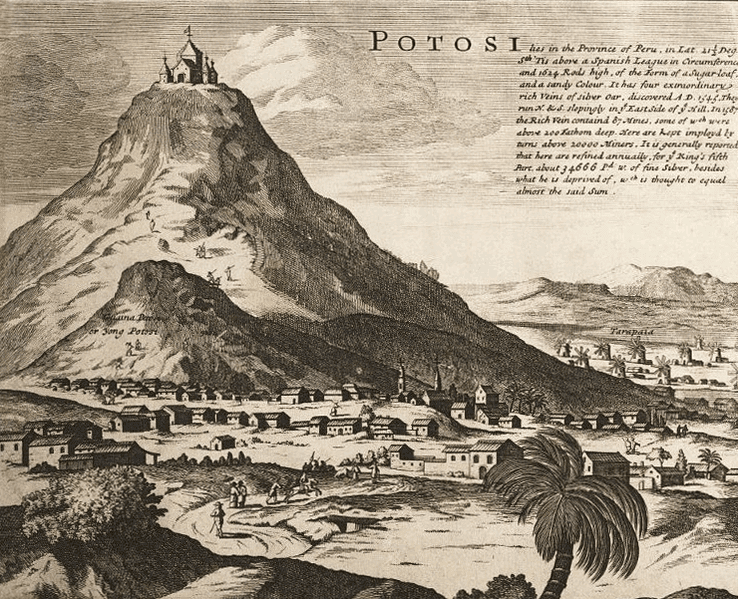

With twice the total population of all of Britain’s North American colonies, Potosí became one of the largest cities in the Americas despite being at an elevation of over 13,000 feet. This expansion centered on the massive silver mines at the nearby Andean mountain of Potosí that fueled Spain’s imperial ambitions. How did the city’s infrastructure keep pace with this startling urban growth?

With twice the total population of all of Britain’s North American colonies, Potosí became one of the largest cities in the Americas despite being at an elevation of over 13,000 feet. This expansion centered on the massive silver mines at the nearby Andean mountain of Potosí that fueled Spain’s imperial ambitions. How did the city’s infrastructure keep pace with this startling urban growth?