In Empire of Poverty, Julia McClure presents an innovative approach to the study of the Spanish Empire. The book analyzes how poverty was conceived in the early years of the Spanish colonization of the Americas, and how it was transformed as attitudes towards the poor were changed by a series of economic, political, religious and social factors. Julia McClure argues that the transition to colonial capitalism in the sixteenth century modified previous attitudes towards poverty and modelled a new approach that shaped the very same institutions of empire.

The most innovative aspect of this work is the analysis of this ideological change. Rather than emphasizing the material aspects of poverty during the transition to capitalism, as previous Marxist analysis have done (in the case of Europe see: Karls Marx’s Capital and Catherina Lys and Hugo Solis’ Poverty and Capitalism in Pre-Industrial Europe), McClure analyzes how the moral-political concepts of empire-building changed and intertwined with social, political and economic factors, eventually influencing the governing models of imperial institutions. As the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the New World and amassed wealth and riches, new theories of monetary value emerged. These theories were accompanied by framing notions of indigenous people as impoverished and ‘‘uncivilized’’, which were constructed to justify Spanish colonization and the subsequent subjugation of these communities. This also explained the emergence of new theories of sovereignty.

Debates regarding the natural rights of Indigenous people and their role in colonial society as well as discussions led by scholars of the School of Salamanca followed the scholastic tradition but also inspired new models of governance. McClure demonstrates how poverty was used as an instrument for the control and subjugation of Indigenous people in the Americas. She identifies this period as the genesis of what she calls ‘‘colonial capitalism’’, marked by the emergence of moral-political values that helped shape new theories of empire and expand sovereignty claims over additional individuals and territories.

Taking a first look at the Iberian Peninsula, the book first delves with the Spanish arbitristas, intellectuals who wrote treatises to the King on the social, political and economic state of the kingdom. It analyzes the impact the New World wealth had in Spanish society at the time, rejecting previous analysis that regarded Spain as an impoverished kingdom. McClure argues that it was the sudden flow of wealth and riches from the New World that helped construct this idea of decline and poverty at home, with the arbitristas being the first to introduce and articulate this concept.

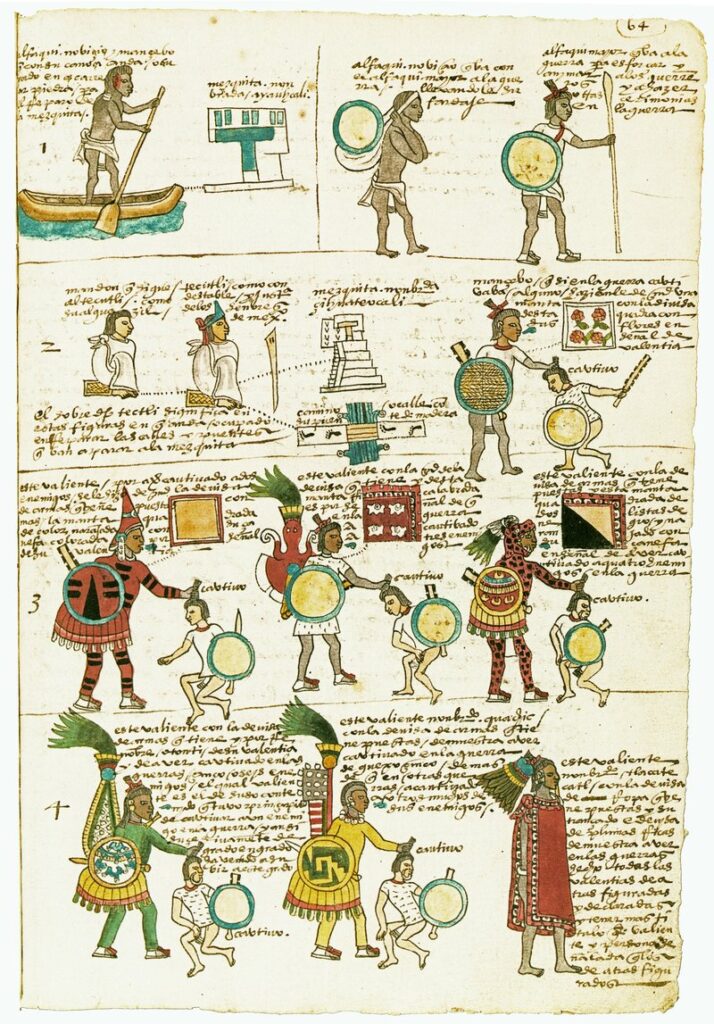

The book then takes the reader to America to first analyze the economies of pre-Columbian societies such as the Maya, Inca or Aztec. McClure argues that these indigenous political entities had their own mechanisms to face poverty and scarcity. She defines these economic systems as ‘‘moral ecologies’’, characterized by their interactions with their surrounding environment and resources. These systems developed their own mechanisms to reduce poverty and scarcity at times of risk, whether that be it as a result of a natural disaster or harvest failure (pp.54-67). Despite the existence of these mechanisms, the author shows how Spanish officials and intellectuals constructed Indigenous people as poor, and began classifying them in different social ranges, often denoting their economic status and racial features. This only mirrored the developments that were happening at the same time in the Iberian Peninsula.

Focusing again in Europe, McClure stresses the importance of the new theories of state and government that were emerging at the time. She defines them as contractual and collaborative in nature, emphasizing the negotiated relationship between vassals and rulers, despite the increasing power of European monarchs. These new theories of state –often embedded within the ‘mirror for princes’ literature– actively supported the provision of the poor and the existence of welfare systems as the monarch was regarded as the main benefactor and provider of the poor and those in need. As a result, intellectuals from the School of Salamanca legitimized the Spanish colonization of the Americas, and with it, the emergence of colonial capitalism. Their theories of sovereignty and government framed the King as the main supporter and provider of welfare and charity in the kingdom, stressing the contractual nature of this negotiated sovereignty.

At the same time, attitudes towards poverty shifted. These shifts in approaches to poverty and poor relief formed part of a wider trend in Europe where the poor began to be increasingly policed and controlled by government institutions. Treaties such as Juan Luis Vives’ De Subventione Pauperum (1530) or Miguel de Giginta’s Tratado de remedio de pobres (1579) offered new solutions to relief poverty and advocated for a tighter control toward vagrancy. New classifications emerged between deserving and undeserving poor, which further widened the gap between legal and illegal forms of poverty. Moreover, the issue of new poor laws during the reigns of Charles V (1516-1556) and Philip II (1556-1598) meant the further criminalization of poverty, and an acceleration in state-controlled legislation (p.126).

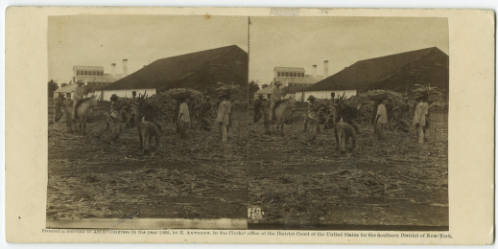

Additionally, the construction of poverty toward Indigenous people often meant their appropriation of their land and labor, which helped further cement the colonial project. McClure analyzes the various forms of labor appropriation and exploitation, including the encomienda system, the repartimiento, and the capture of individuals in combat through just war rhetoric (pp.138-142). In addition, as a result of the creation of novel forms of debt and tributary legislation, new forms of poverty emerged that widely affected Indigenous communities. The appropriation of lands and the legal mechanisms used to claim ‘empty’ lands or legalized already occupied ones, formed a model that ultimately favored Spanish colonists (p.164).

At the same time, the categorization of Indigenous people as ‘‘childish’’ and in need of protection helped Spanish officials to implement further governing structures in the Americas, strengthening the visualization of the Spanish Monarchs as the benefactors of these communities. The Crown exploited this discourse to build around its institution the myth of protector of the Indians and dispenser of justice. Yet, McClure also shows that Indigenous people navigated through the intricate system of Spanish colonial law, and often sought rewards and compensation for their miseries and poverty. This bottom-up system of petitions, rewards, and amparos also shaped the imperial institutions of the Spanish empire in the New World, and created a precedent for a passive resistance and cemented the survival of pre-conquest privileges and rights among Indigenous people and communities (pp.172-173).

In conclusion, Empire of Poverty shows how moral and political concepts of poverty influenced the governing institutions of the Spanish empire while also laying the foundations for the modern unequal systems that affect the exact same societies that were first colonized in the sixteenth century. Simultaneously, the monograph shifts attention from the Anglophone historiographical tradition that has usually overemphasized the Protestant models to study poverty and charity (highly influenced by Weber’s thesis on the Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism) to explain early modern attitudes towards poverty. This offers a new paradigm to explain the role and impact of Catholicism in poor relief and poverty management.

As a result, McClure concludes that scholars and officials of the Spanish Empire ‘reinvented poverty’ to legitimize their expansion of sovereignty in these new territories. In doing so, they created new forms of poverty through alien systems of labor extraction, tribute collection, and land appropriation. Despite this, the negotiated and participative nature of the Spanish empire also enabled its vassals to negotiate and even lobby for their own interests. At times, this led to the preservation of their rights and status, or the obtaining of rewards, in the newly created colonial society, evidencing the participatory and contractual nature of this system of rule and government. Finally, McClure stresses how the colonial capitalist model that developed over the sixteenth century paved the way for modern inequalities that continue in these territories, often shaping Indigenous ways of life and survival.

Jorge García-García is a first-year PhD History student at the University of Texas-Austin. He studied History as an undergraduate at the University of Glasgow (United Kingdom), obtaining a MA with Honors of the First Class. He then studied a postgraduate degree in World History at the Pompeu Fabra University (Spain). His research focuses on Colonial Latin America and the Spanish Empire.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

by

by