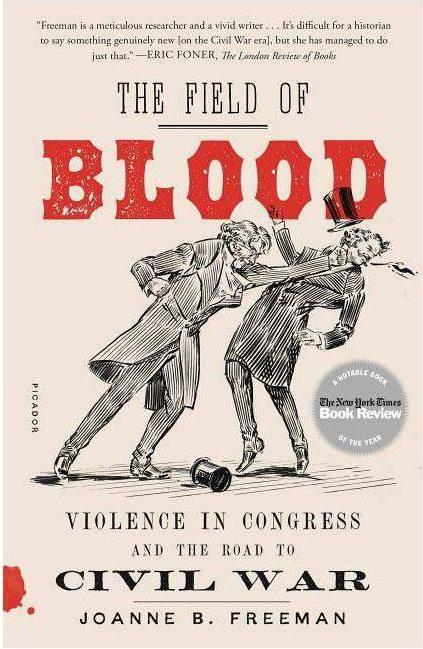

The Field of Blood is a timely publication that examines congressional violence in antebellum America. The work reorients our understanding of the road to American disunion and the political conflicts that dominated Congress in the three decades before the Civil War. Freeman has unearthed an overlooked history of congressional brawls, fights, duels, and other violent encounters between northern and southern representatives on the Senate and House floors. These violent conflicts were more than personal disputes and petty quarrels. Freeman shows how these incidents were representative of larger sectional tensions and were entangled in a web of party loyalty, personal honor, and regional pride.

One of the joys of reading this work was Freeman’s superior prose. It is at once witty and poignant as she guides readers through a violent world of congressional brawls, fistfights, and canings without sensationalizing the subject matter. Many of the incidents she describes are stomach churning and attention-grabbing in their own right, yet Freeman manages to integrate incidents of congressional violence into a more significant narrative of sectional tension, institutional mistrust, and ideology. Each chapter follows one violent incident as experienced by Freeman’s historical tour-guide, Benjamin Brown French. French was a house clerk from New Hampshire who spent thirty-seven years in Washington D.C. from 1837 to 1870 surrounded by Congressmen and witness to their violent quarrels. Freeman uses Brown’s extensive diaries as guides to the congressional world of “friendships and fighting; of drinking and dallying; of the passions of party and the prejudices of section and how they played out on the floor.” The diaries also personify the way the nation changed over time. Freeman often uses French as an embodiment of the political transformations that took place in the antebellum period. His loyalties, friendships, and party affiliation evolved as southern violence, sectional tension, and fears of a domineering block of slaveholders at the heart of the national government (known as Slave Power) altered party membership and political ideology in the 1840s and 1850s.

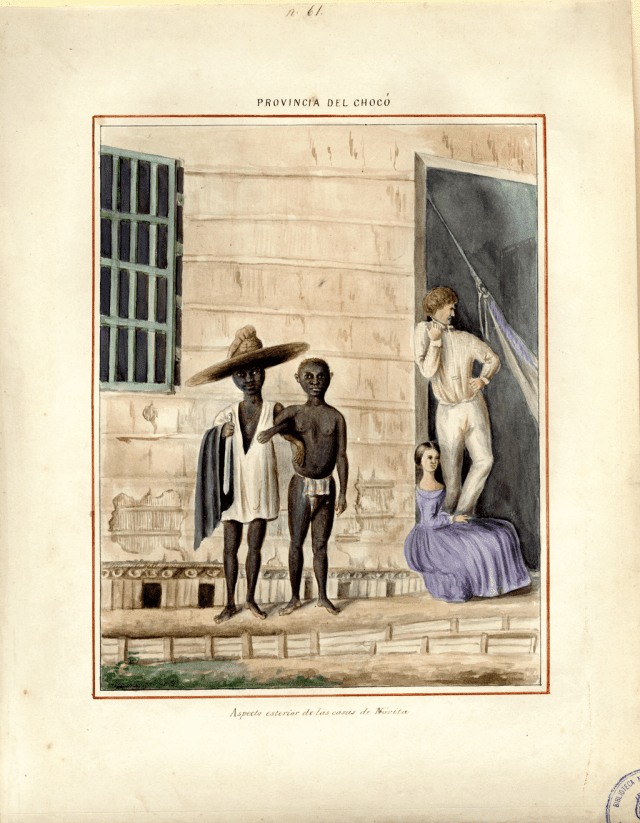

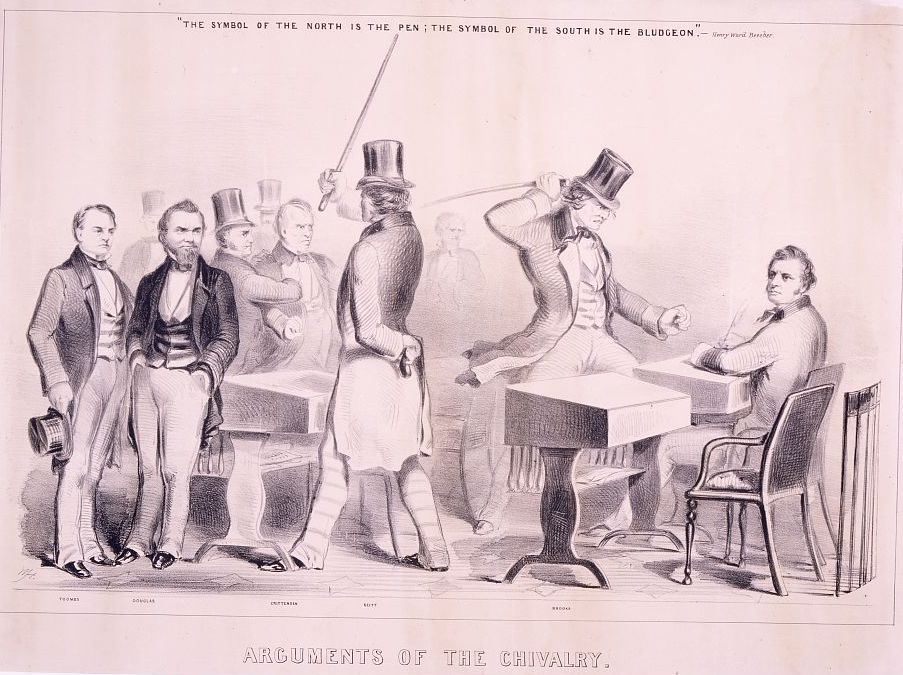

Arguments of the chivalry,1854 (via Library of Congress)

Many of the stories Freeman tells will be well known to students of antebellum American history, but what makes The Field of Blood so innovative is that Freeman shows the role of emotions and values in the political and ideological divisions that led to the Civil War. Freeman’s retelling of Preston Brooks’ caning of Charles Sumner, for example, highlights the importance of honor, pride, loyalty, and patriotism in Northern reactions to the Sumner tragedy. On May 22, 1856, Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina brutally beat Senator Charles Sumner with his cane until it shattered. Brooks believed that Sumner insulted him personally and politically by admonishing Brooks’ relative Andrew Butler in an anti-slavery speech about the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Honor, pride, and loyalty played a role in Brooks’ motivation to defend Andrew Butler, South Carolina, and the rest of the South against Sumner’s supposed insult. However, honor, pride, and loyalty also played a central role in Republican responses to the violent act. While, the brutality of Brooks’ violence was cause for outrage in the North, it was Brooks’ violation of the rules of congressional combat that infuriated and offended Northerners. Previously, most acts of physical violence on the congressional floor were spontaneous encounters, whereas Brooks’ attack was premeditated. Brooks also elevated the political stakes of his attack by beating Sumner on the congressional floor rather than outside where personal disputes could be settled apart from political ones. Freeman shows how the location and timing of the Brooks-Sumner encounter exacerbated regional tensions and gave Northerners an opportunity to play up the notion of Southern violence in the press. Brooks’ violent escapade was the personification of pro-slavery brutality and arrogance.

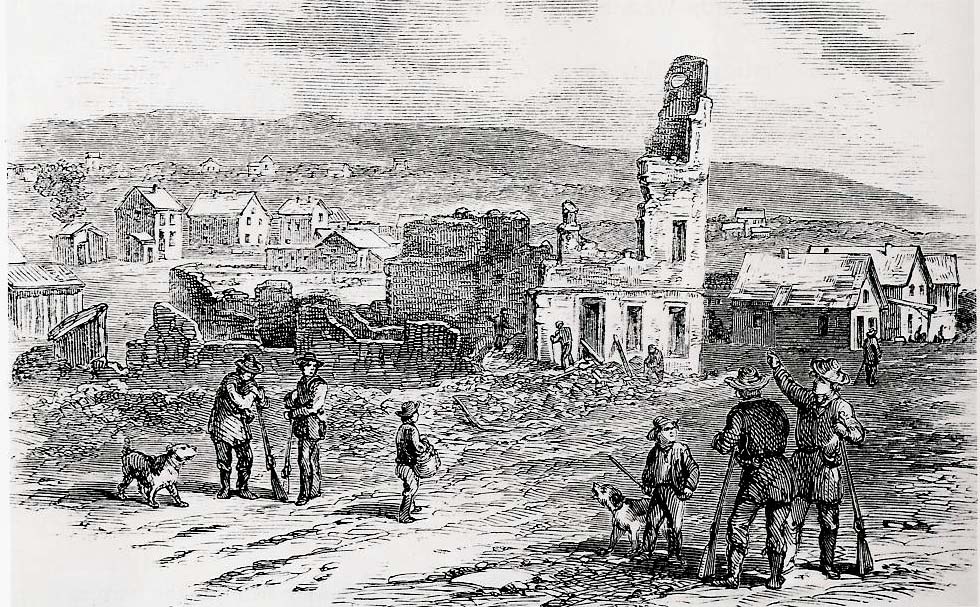

Sacking of Lawrence (via Wikipedia)

Further intensifying the strong reactions, Sumner’s caning occurred around the same time as antislavery settlers were ransacked by proslavery aggressors in Lawrence, Kansas. Northerners viewed these violent encounters as a series of ongoing attacks against the North by the Southern Slave Power and believed the attacks would not stop until the North fought back to take control of the future of the Union. The rise of congressional violence in the 1850s exemplified the civic breakdown and unyielding polarization in Congress that made war seem inevitable. By the end of Freeman’s book, it feels unbelievable that it had taken so long for someone to tell the story of disunion through the lens of congressional violence. As she reminds readers early on in her work, “The nation didn’t slip into disunion; it fought its way into it, even in Congress.”

Freeman’s work breathes life into what often feels like a stagnant field of antebellum political history. Her use of violence as an analytical category provides a new framework for understanding the nation in the antebellum period that synthesizes the existing literature and illuminates an overlooked component of American political development. By deploying emotion and honor in her work, Freeman proves that there is still more to explore in what often feels like an overly dense field and time period of American history. The Field of Blood reassures students and scholars that there are still unchartered territories to explore in the antebellum period.

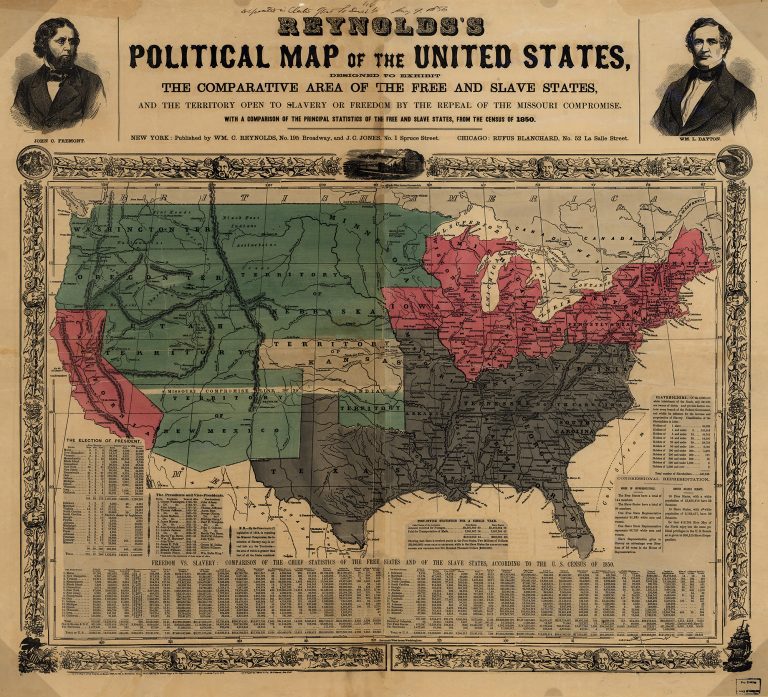

Political Map of the United States, 1856 (via Wikimedia Commons)

The Field of Blood will do for historians of the antebellum period what Freeman’s 2001 work, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic, did for historians of the early republic. Her discovery of a “culture of honor” that guided politics in the early republic provided a new way of thinking about political conflict and nation-building in the 1790s. Affairs of Honor was one of the first books I read as undergraduate history major and I returned to the book this fall, delighted all over again by its reinterpretation of the history of the young United States. In that book, Freeman showed how previously undervalued and overlooked modes of political communication, such as political gossip and print culture, affected reputations of political leaders and influenced political alliances and elections. She provides a connecting line from Affairs of Honor to Field of Blood through her repeated methodological use of emotion and honor to dissect patterns of political thought and political behavior in the first seventy years of the nation’s existence.

At a time when congressional polarization and violent political rhetoric have reached an unimaginable height, Freeman’s work feels especially significant. Current party strife and widespread disillusionment mirror similar political developments of the antebellum period in chilling ways. The web of fanatical party loyalty, excessive personal pride, and regional tension that Freeman exposes in her work echoes in the contemporary halls of the U.S. Capitol and Oval Office. The Field of Blood confirms that the time is ripe for a resurgence of historical scholarship that examines the early political development of the United States, which can shed light on our own puzzling state of political disarray.

![]()

You might also like:

This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War by Drew Gilpin Faust (2008)

Harper’s Weekly’s Portrayal of the Civil War: The New Archive (No. 11)

IHS Talk: “The Civil War Undercommons: Studying Revolution on the Mississippi River” by Andrew Zimmerman

![]()