In 1963, Dennis Duerden of the Transcription Centre in London and Henry Doré of the National Educational Television Centre in New York collaborated with prominent South African writer Lewis Nkosi to develop a television series featuring leading African artists and writers of late-colonial and early-independent Africa. As part of the project, Duerden corresponded with Kenyan writer, Grace Ogot—the only woman writer whose life and work the series intended to explore. The documents exchanged between Duerden and Ogot (currently housed at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin) offer glimpses into the intent of the television project, the relationship between Anglo-American and African personalities in the early 1960s, and the intellectual lives of Duerden and Ogot during the period of their exchange.

On June 22, 1963, Duerden initiated a series of letters with Ogot regarding the proposed television series. Duerden’s first letter was accompanied by a questionnaire, which Ogot was requested to complete. The questionnaire, developed by Nkosi and Duerden, was intended to gather biographical information about the writer before Duerden and his team began production on the film series. Ogot returned the questionnaire with reticent answers.

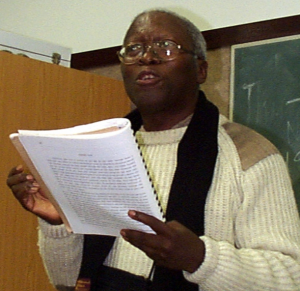

Lewis Nkosi at the Centre for the Study of Southern African Literature and Languages (CSSALL) at the University of Durban-Westville (UDW), 2001. Via Wikipedia

Consequently, Duerden wrote a follow-up letter to Ogot, requesting that she include greater biographical detail in her answers. In his letter, Duerden endorsed the value of the television project, hoping its worth would inspire Ogot to be more forthcoming. Whether or not Ogot was convinced of the project’s value, she filled out the questionnaire the second time with significantly more revealing information.

In Ogot’s second set of answers, we encounter glimpses of her values, interests, and intellectual life. For example, we learn that her primary literary influences included the short story “How Much Land Does a Man Require” by Leo Tolstoy, The Dark Child by Camara Laye, Mary Slessor of Calabar by William Pringle Livingstone, and Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe. Ogot elaborated on the significance of these works in her life. Tolstoy’s short story, for instance, prompted her to write: “If the whole world read this story, perhaps there would be no war.” Regarding the biography of Mary Slessor by Livingstone, Ogot explained, “If anything at all, this book had a lot to do with the shaping of my life and the choice of my career.” Seeking to emulate the positive impact that Slessor had on African society, Ogot “became a nurse … I regarded this as an expression of that feeling of gratitude in me towards Mary Slessor of Scotland who did so much for my Africa.”

The television project as a whole intended to help a burgeoning African literary scene develop parameters for what might be called “African literature.” To this end, the fifth question on the questionnaire is perhaps the most illuminating. “WHAT DO YOU CONSIDER TO BE SPECIFICALLY AFRICAN INFLUENCES IN YOUR LIFE …?” The question presumes the existence of a tangible “Africanness” which is also reflected in the discourse of late-colonial and early-independent Africa, where African identities and trajectories of peoples, nations, and the continent were all being negotiated. Duerden’s second letter to Ogot unpacks the intention of this question further: “What we want to do is to establish how far the background of your people’s traditions have affected the texture of your life.” The question arises: What does it mean to the author of the questionnaire to be “African” in texture and influence?

Initially, Ogot offered very little in terms of a response to the fifth question. In fact, she chose to write, “NIL.” Yet when Duerden begged for more elaborate answers, Ogot disclosed what she considered to be the “African influences” coloring her life:

“Looking back now, I think that there were some African influences that affected my marriage. An English friend of mine asked me once, “After all these years of Education, you still want to be married according to African customs?” My answer was simple. “There is something terribly African in me that school education has not touched.” The negotiations about my marriage were done according to Luo tradition, and full dowry was paid.”

Ogot went on to summarize her wedding day and highlight some of the specific Luo rituals to which she adhered. Interestingly, Ogot had begun to write that the negotiations regarding her marriage were done according to “African” tradition; however, at “Afri” she stopped and scribbled out the word, replacing it with “Luo”, as quoted above. In the struggle against colonialism, which necessitated a certain unity among African peoples, Ogot’s response displays her active negotiation and mediation of her identity, imagined somewhere in between “Luo” and “African.” Her initial dismissal of the question might also suggest that “Africanness” to her was something embodied rather than something that could be divorced from context, defined, and analyzed. Indeed, in her response, she defines “African influences” as “something terribly African in [her].”

Following her participation in the television series, Ogot went on to publish short stories and novels, including The Promised Land (1966) and a collection of short stories entitled Land Without Thunder (1968). Luo history and tradition saturated her fiction. Yet, Ogot is also remembered for her prominent role in Kenyan national politics. Thus her life’s work reflects the plurality of identities—local, national, and continental—that confronted African literary elite in the wake of African independence. Rather than conclusively answering the question, “What is African Literature?,” the television series on prominent African writers served to expose the tensions underlying such plurality.

Sources:

Box 17, Folder 21, The Transcription Centre Records, Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas, Austin.