In the months following his resounding electoral triumph over Barry Goldwater in November 1964, President Lyndon Baines Johnson made momentous decisions to escalate U.S. military involvement in Vietnam. Most consequentially, he ordered the bombing of North Vietnam: first retaliatory strikes following a National Liberation Front attack on the U.S. base at Pleiku and then a sustained bombing campaign called Operation Rolling Thunder. Critics of the administration’s decision-making feared that these steps would commit the United States to a difficult and unnecessary war and appealed urgently for a change of course. One such appeal came from Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, who focused not just on geostrategic dangers but also, more unusually, on the domestic political risks. In a memorandum to the president ten days after the Pleiku attack, Humphrey warned that the American public had little enthusiasm for a major war and that escalation might damage the administration and the Democratic Party more generally. Although there is no definitive evidence that Johnson read the memo, one of Johnson’s aides, Bill Moyers, later stated that he had given it to the president.

I would like to share with you my views on the political consequences of certain courses of action that have been proposed in regard to U.S. policy in Southeast Asia. I refer both to the domestic political consequences here in the United States and to the international political consequences.

A. Domestic Political Consequences.

1. 1964 Campaign.

Although the question of U.S. involvement in Vietnam is and should be a non-partisan question, there have always been significant differences in approach to the Asian question between the Republican Party and the Democratic Party. These came out in the 1964 campaign. The Republicans represented both by Goldwater, and the top Republican leaders in Congress, favored a quick, total military solution in Vietnam, to be achieved through military escalation of the war.

The Democratic position emphasized the complexity of a Vietnam situation involving both political, social and military factors; the necessity of staying in Vietnam as long as necessary; recognition that the war will be won or lost chiefly in South Vietnam.

In Vietnam, as in Korea, the Republicans have attacked the Democrats either for failure to use our military power to “win” a total victory, or alternatively for losing the country to the Communists. The Democratic position has always been one of firmness in the face of Communist pressure but restraint in the use of military force; it has sought to obtain the best possible settlement without provoking a nuclear World War III; it has sought to leave open face-saving options to an opponent when necessary to avoid a nuclear show-down. When grave risks have been necessary, as in the case of Cuba, they have been taken. But here again a face-saving option was permitted the opponent. In all instances the Democratic position has included a balancing of both political and military factors.

Today the Administration is being charged by some of its critics with adopting the Goldwater position on Vietnam. While this is not true of the Administration’s position as defined by the President, it is true that many key advisors in the Government are advocating a policy markedly similar to the Republican policy as defined by Goldwater.

2. Consequences for other policies advocated by a Democratic Administration.

The Johnson Administration is associated both at home and abroad with a policy of progress toward detente with the Soviet bloc, a policy of limited arms control, and a policy of new initiatives for peace. A full-scale military attack on North Vietnam – with the attendant risk of an open military clash with Communist China – would risk gravely undermining other U.S. policies. It would eliminate for the time being any possible exchange between the President and Soviet leaders; it would postpone any progress on arms control; it would encourage the Soviet Union and China to end their rift; it would seriously hamper our efforts to strengthen relations with our European allies; it would weaken our position in the United Nations; it might require a call-up of reservists if we were to get involved in a large-scale land war–and a consequent increase in defense expenditures; it would tend to shift the Administration’s emphasis from its Great Society oriented programs to further military outlays; finally and most important it would damage the image of the President of the United States – and that of the United States itself.

3. Involvement in a full scale war with North Vietnam would not make sense to the majority of the American people.

American wars have to be politically understandable by the American public. There has to be a cogent, convincing case if we are to have sustained public support. In World Wars I and II we had this. In Korea we were moving under UN auspices to defend South Korea against dramatic, across-the-border conventional aggression. Yet even with those advantages, we could not sustain American political support for fighting the Chinese in Korea in 1952.

Today in Vietnam we lack the very advantages we had in Korea. The public is worried and confused. Our rationale for action has shifted away now even from the notion that we are there as advisors on request of a free government – to the simple argument of our “national interest.” We have not succeeded in making this “national interest” interesting enough at home or abroad to generate support.

4. From a political viewpoint, the American people find it hard to understand why we risk World War III by enlarging a war under terms we found unacceptable 12 years ago in Korea, particularly since the chances of success are slimmer….

5. Absence of confidence in the Government of South Vietnam.

Politically, people can’t understand why we would run grave risks to support a country which is totally unable to put its own house in order. The chronic instability in Saigon directly undermines American political support for our policy.

6. Politically, it is hard to justify over a long period of time sustained, large-scale U.S. air bombardments across a border as a response to camouflaged, often non-sensational, elusive, small-scale terror which has been going on for 10 years in what looks like a civil war in the South.

7. Politically, in Washington and across the country, the opposition is more Democratic than Republican.

8. Politically, it is always hard to cut losses. But the Johnson Administration is in a stronger position to do so than any Administration in this century. 1965 is the year of minimum political risk for the Johnson Administration. Indeed it is the first year when we can face the Vietnam problem without being preoccupied with the political repercussions from the Republican right. As indicated earlier, the political problems are likely to come from new and different sources if we pursue an enlarged military policy very long (Democratic liberals, Independents, Labor, Church groups).

9. Politically, we now risk creating the impression that we are the prisoner of events in Vietnam. This blurs the Administration’s leadership role and has spill-over effects across the board. It also helps erode confidence and credibility in our policies.

10. The President is personally identified with, and admired for, political ingenuity. He will be expected to put all his great political sense to work now for international political solutions. People will be counting upon him to use on the world scene his unrivalled talents as a political leader.

They will be watching to see how he makes this transition. The best possible outcome a year from now would be a Vietnam settlement which turns out to be better than was in the cards because the President’s political talents for the first time came to grips with a fateful world crisis and so successfully. It goes without saying that the subsequent domestic political benefits of such an outcome, and such a new dimension for the President, would be enormous.

11. If on the other hand, we find ourselves leading from frustration to escalation, and end up short of a war with China but embroiled deeper in fighting with Vietnam over the next few months, political opposition will steadily mount. It will underwrite all the negativism and disillusionment which we already have about foreign involvement generally – with direct spill-over effects politically for all the Democratic internationalist programs to which we are committed – AID, UN, disarmament, and activist world policies generally.

B. International Political Implications of Vietnam.

1. What is our goal, our ultimate objective in Vietnam? Is our goal to restore a military balance between North and South Vietnam so as to go to the conference table later to negotiate a settlement? I believe it is the latter. If so, what is the optimum time for achieving the most favorable combination of factors to achieve this goal?

If ultimately a negotiated settlement is our aim, when do we start developing a political track, in addition to the military one, that might lead us to the conference table? I believe we should develop the political track earlier rather than later. We should take the initiative on the political side and not end up being dragged to a conference as an unwilling participant. This does not mean we should cease all programs of military pressure. But we should distinguish carefully between those military actions necessary to reach our political goal of a negotiated settlement, and those likely to provoke open Chinese military intervention.

We should not underestimate the likelihood of Chinese intervention and repeat the mistake of the Korean War. If we begin to bomb further north in Vietnam, the likelihood is great of an encounter with the Chinese Air Force operating from sanctuary bases across the border. Once the Chinese Air Force is involved, Peking’s full prestige will be involved as she cannot afford to permit her Air Force to be destroyed. To do so would undermine, if not end, her role as a great power in Asia.

Confrontation with the Chinese Air Force can easily lead to massive retaliation by the Chinese in South Vietnam. What is our response to this? Do we bomb Chinese air bases and nuclear installations? If so, will not the Soviet Union honor its treaty of friendship and come to China’s assistance? I believe there is a good chance that it would–thereby involving us in a war with both China and the Soviet Union. Here again, we must remember the consequences for the Soviet Union of not intervening if China’s military power is destroyed by the U.S.

Photo Credits:

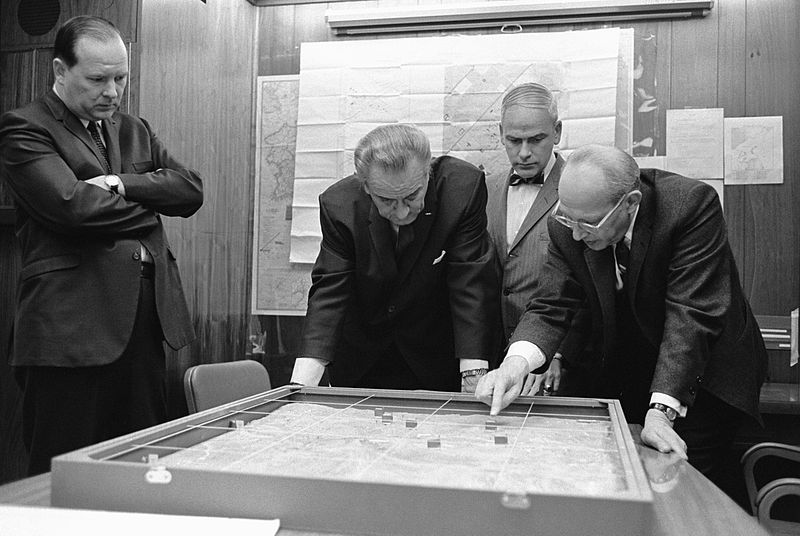

Lyndon Johnson examining a model of the Khe Sanh region of Vietnam in the White House Situation Room, 1968 (Image courtesy of the U.S. Federal Government)

President Johnson meets U.S. troops in Vietnam, 1966 (Image courtesy of the U.S. Department of State)

Man surveying the damage from a Viet Cong bomb attack against a multi-story U.S. officers billet in Saigon, 1966 (Image courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration)

Members of the 101st Airborn Division aboard a USAF C-130 at Pham Thiet Air Base, Republic of Vietnam, for airlift to Phi Troung Air Base (Image courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration)

U.S. pilots bomb a military target over North Vietnam, 1966 (Image courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration)