By Ann Twinam

Let’s start with a question and a comparison.

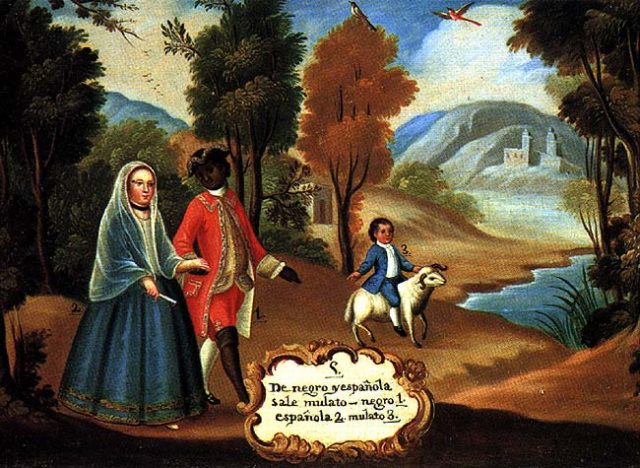

What do you think would have happened if a free mulatto — someone of mixed white and African heritage — living in New York or Virginia, had sent a letter to either of the Georges, either King George III (1760-1820) or President George Washington (1789-1797) asking if he might purchase whiteness? Do you think he would have even received a reply, much less transformation to the status of white? The very idea that mulattos could pay to become “whites” or that an English king or a U.S. president might grant such a change seems unbelievable — because it was.

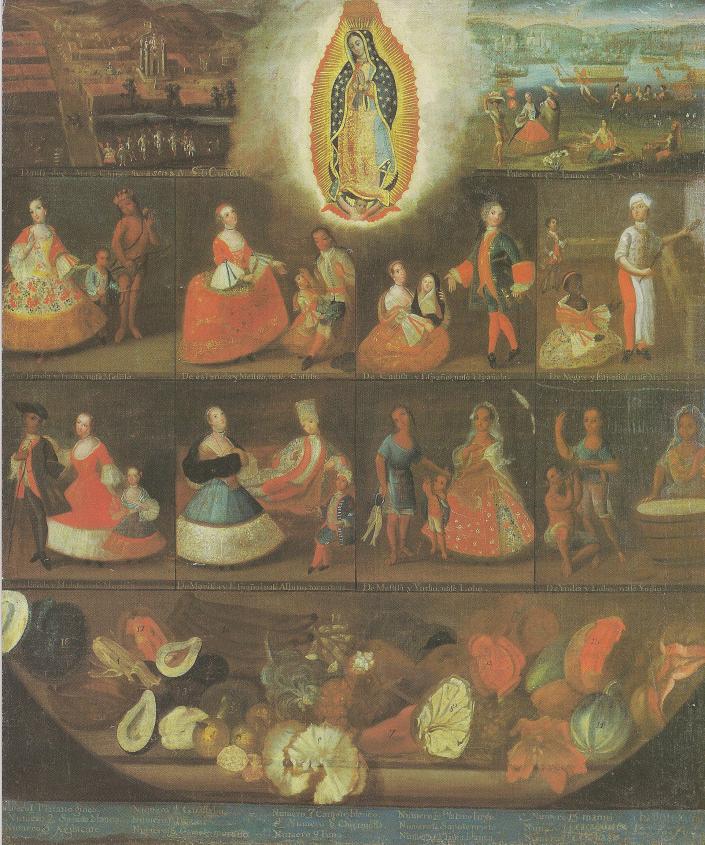

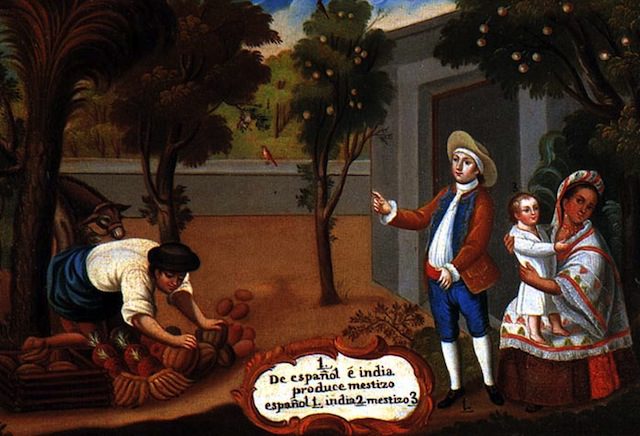

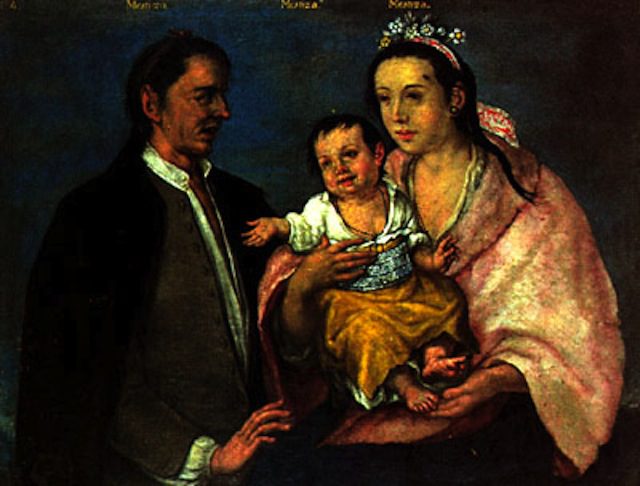

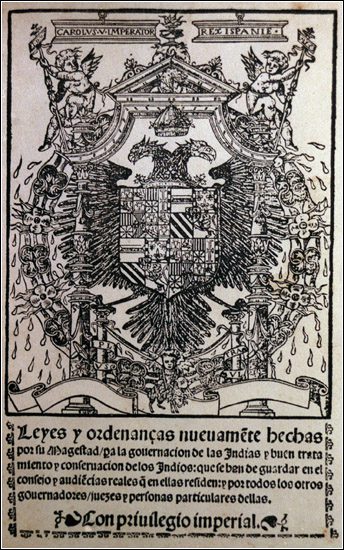

Yet, during the same period in the Spanish empire, such alterations for mulattos –also known as pardos or castas — became possible. This was so, even though the Spanish state had also institutionalized severe discriminations against those of mixed African descent, just as in the British Empire and in the American republic. Laws forbade their practice of numerous occupations including physician, notary, lawyer, priest, the holding of public offices, service in the regular military, entrance to universities, and marriages with whites. Still, it was also possible for Cuban Manuel Baez to receive a royal decree in 1760 that erased “the defect that you suffer from birth and leave you able and capable as if you did not have it, repealing this time in your favor whatever laws, ordinances or constitutions speak otherwise.”

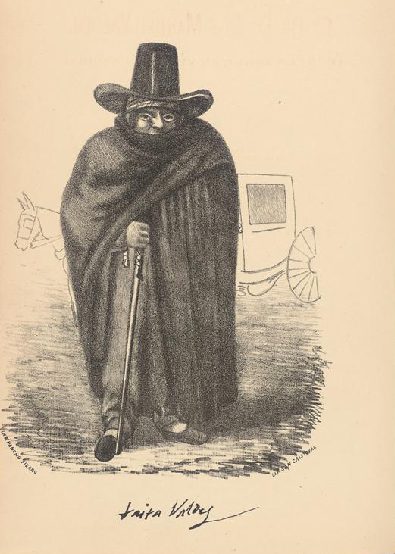

By 1795, the Spanish crown had institutionalized the purchase of whiteness through a process called the gracias al sacar. An elite cohort of pardos and mulattos could apply and pay for a decree that converted them to whites. In 1796, merchant Julian Valenzuela bought a decree from the king and Council of the Indies that “dispensed” his status as a “pardo.”

At the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries in Spanish America,there was vigorous and serious debate concerning the civil rights of those of mixed descent. It not only led the Council of the Indies to endorse the continued whitening of deserving pardos and mulattos, but also to consider eliminating some of the discriminations against all the castas. It meant that by 1812, the Cortes of Cádiz, tasked with writing a constitution for the Spanish empire, would continue to widen opportunities for pardos and mulattos by ordering the desegregation of universities throughout the Indies. Such actions would occur 150 years before the U.S. government in the 1960s would demand similar measures for colleges and universities.

Such contrasts between Spanish and Anglo America lead to other questions. What made it possible for pardos and mulattos in the Spanish empire in the mid eighteenth century to apply for whiteness? Why would the crown take them seriously? What does this reveal about the different histories and the different ways that the Anglo and the Iberian worlds have constructed and treated issues of race?

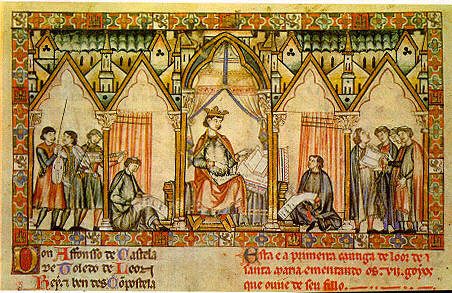

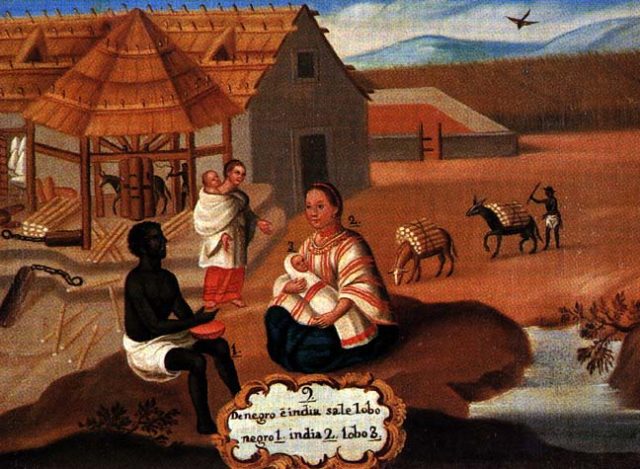

Some deep-rooted Spanish practices facilitated the progression from slavery to freedom to vassalage that enabled mutable racial status. Even as both sides of the Spanish Atlantic acknowledged hierarchies of exclusion that privileged whiteness and rank, some possibilities for inclusion remained open. The medieval law code of the Siete Partidas (1252-1284), for example, acknowledged that slaves would naturally seek freedom, establishing the potential for purchase or grant of liberty with the acquiescence of the state.

Spanish traditions also uniquely combined with the American environment to open interstices for newly arrived Africans to negotiate pathways. The legal recognition that free women always gave birth to free babies had an incalculable impact in the Americas, given the potential motherhood of millions of indigenous women. It provided male slaves with the option of automatically freeing sons and daughters borne by Native and later by free casta partners. Slaves, free blacks, pardos, and mulattos could access the system, seeking legal remedies for mistreatment. Laws proved color blind, permitting acquisition of possessions, as well as secure passage of property to succeeding generations.

The passage of time also mattered. The first waves of Africans disembarked centuries earlier in the Indies than in Anglo America. The royal insistence that slaves become Catholics also had a profound influence, even though African beliefs persisted and blended. As the centuries passed, a shared religion united the inhabitants of the Indies forging them into a Spanish Catholic “us.” Because they were coreligionists and neighbors whose families had lived for generations in the Americas, blacks, pardos, and mulattos in the 1620s and 1630s received permission to organize militia units and take up arms with whites to defend their mutual homeland against foreign enemies.

Such evidence of royal service moved participating castas from the category of “inconveniences,” to the status of vassals enjoying the traditional benefits of reciprocity. Those who performed services had the right to request favors; the duty of the monarch was to reward them. For that reason, the Council of the Indies would seriously consider the casta petitions that arrived in the mid eighteenth century requesting the purchase of whiteness. The history of the whitening gracias al sacar thus becomes inextricably linked to centuries of struggles by Africans and their mixed-blood descendants to move from slavery to freedom, to status as vassals, and finally, after independence, to citizenship.

The gracias al sacar emerges as but one variant — an official one — of widespread and unofficial practices that had facilitated pardo and mulatto mobility for centuries. The ability to purchase whiteness proved critical, but not because of the few who applied for it or the even fewer who received it. Rather, its history coincides with this larger and mostly untold story of casta mobility in Spanish America. The extent to which such struggles failed and succeeded provides striking insight into those processes of exclusion and inclusion that shaped the texture of discrimination within the Spanish empire. Understanding those differences highlights the divergent historical paths followed in Anglo and Latin America, the consequences of which reverberate even today.

Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulattos and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies by Ann Twinam

To read more about interpretations of race and status in colonial Latin America, click here.

Articles on Not Even Past about race and slavery in Latin American can be found here.