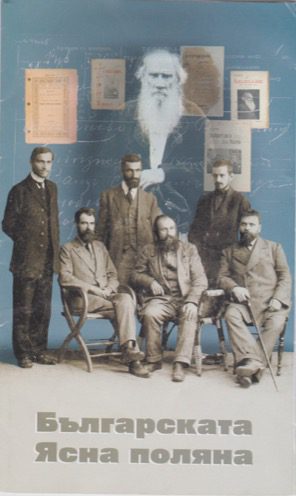

It seemed like a bad idea then, but I did it anyway. Maybe, just maybe, there was hope that the little museum in the Bulgarian mountain village of Yasna Polyana would be open. Established in 1998, the museum contained the intellectual remnants of the Bulgarian Tolstoyan community, who had created an agricultural commune in the village of Alan Kayryak in 1906-07. They renamed the village “Yasna Polyana” (clear meadow) after Leo Tolstoy’s famous estate, Yasnaya Polyana.

I had visited Bulgaria’s Yasna Polyana–with its shortened adjective form “yasna” (instead of “yasnaya”) before. Two summers ago I had made the long trip, braving the bumpy windy roads of the Bulgarian Strandja—a mountainous region on the SW coast of Bulgaria where the village is perched. But that summer my efforts had been in vain. The museum was closed and locked “for renovation.” As I peeked through the dusty windows in frustration, huge storks looked down on me from their nests on the nearby utility poles. They seemed to laugh at my American optimism, until I finally gave up.

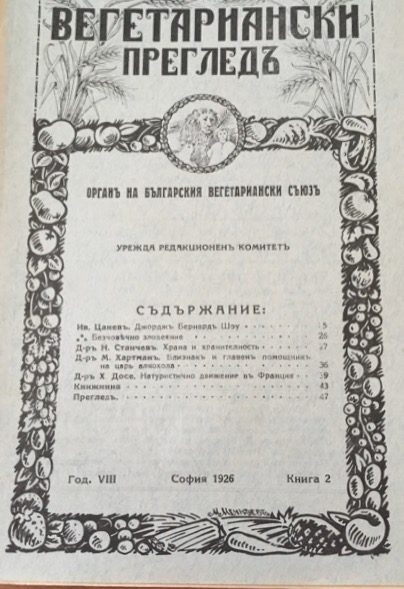

And yet I returned this summer, without confirming that they were open; I could find no phone number or email online. This time google maps betrayed me, sending me down what seemed to be a sheep trail in my rental car. Still, I made it through intact and, as luck would have it, the wonderful curator of the museum was there! She generously allowed me to peruse their collection of crumbling old newspapers, carefully stacked in a back cupboard. As I gleefully thumbed through the materials, snapping pictures on my iphone, the fascinating world of the Bulgarian Tolstoyans opened up to me.

Tolstoy was a figure of global importance in this period. It was not just his famous novels—like War and Peace and Anna Karenina—that brought him fame. He became a towering figure in global exchanges about the moral and ethical concerns of the day. His essays and other writings made him into an intellectual leader and model on a range of philosophical, spiritual, and social questions. Tolstoy cultivated contacts with like-minded people from around the world, though he never approved of the idea of a “Tolstoyan” movement.

And yet one emerged. Before and after his death in 1910, Tolstoyan communes mushroomed around the world, from the US to South Africa—where Mahatma Gandhi set up an ashram named the “Tolstoy colony” near Johannesburg. At the same time, many of the Bulgarian movement’s leaders made the pilgrimage to Tolstoy’s estate in Russia’s Tula province. Khristo Dosev, for example, spent a number of years in residence there and became extremely close to Tolstoy and his inner circle. Dosev became a direct line of contact between Tolstoy and his followers back in Bulgaria. They translated, published, and made every effort to popularize the ideas of Tolstoy in Bulgaria.

By 1907 Bulgarian Tolstoyans had broken ground on their own agricultural commune in Yasna Polyana. Its adherents established a number of agricultural communes across Bulgaria in the years that followed, but Yasna Polyana remained the movement’s epicenter. Its members set up their own printing press for its many publications, which stressed “Tolstoyan” ideas like non-violence, but also temperance, and vegetarianism. The ties to Tolstoy were so strong that many claim that he was headed to Bulgaria in his final days—when he famously left his family estate and headed south. Alas he died along the way. But if anything the Tolstoyan movement gained in strength after his death, especially in the aftermath of World War I. The massive human casualties of the war brought an even greater urgency to the Bulgarian (and global) Tolstoyan project.

In the Bulgarian Tolstoyan museum on that hot July day, I was most interested in the vegetarian strand of the commune’s intellectual and organizational work. I focused my reading (and scanning) on the Bulgarian Tolstoyan newspaper Vegetarian Review (Vegetarianski Pregled), edited by an important member of the movement, Stefan Andreichin. The history of vegetarianism in Bulgaria will be featured in my book on the history of food in Bulgaria. In a chapter that focuses on meat, I will explore the making of a modern meat-eating culture, but also on the vegetarian counter culture that hotly opposed this transition.

This story is best told in global context, and meat was one of the most hotly debated food sources in history—in the past as today. Is eating meat a human instinct, or a learned behavior? Is it the gold standard of fortification or will it kill us? Even if it is good for the human body, what about the ethics of killing animals, the implications of modern methods, or the environmental impacts of meat-eating?

These questions and many more were debated on the pages of Vegetarian Review, in the years between the World Wars. For philosophical grounding, its contributors looked to ideas on vegetarianism that Tolstoy’s famous 1892 essay, “The First Step,” linked to non-violence and Christian ethics (along with a range of other spiritual traditions). Bulgarian Tolstoyans also sought intellectual scaffolding for their vegetarian convictions in famous ancient, medieval and modern vegetarians—from Pythagoras to Buddha, and Henry George to George Bernard Shaw. In addition, the journal featured articles on vegetarian strictures embedded within movements of local origin–namely the Thracian worshippers of the poet, musician, and prophet Orpheus and the eleventh-century dualist Christian sect, the Bogomils.

This preoccupation with historical precursors was coupled with a pointed critique of the industrial machine of modern animal slaughter and meat processing. In Vegetarian Review, “civilization” was derided for turning people into pleasure seeking “machines,” that could “swallow muscles and gnaw on bones” of poor innocent animals. The Chicago stockyards—since the late nineteenth century the epicenter of modern meat production–were seen as a kind of mass death camp. As an article on the pages of Vegetarian Review alleged, “In just one world city, Chicago, 54 million animals, cows, lamb, sheep, pigs and others are killed a year, with enough blood flowing from them to fill a huge reservoir.”

This clear ambivalence towards “progress,” however, did not preclude the Tolstoyans from formulating a vision of the future. Indeed, far from retreating into the past, Tolstoyan authors advocated change, a “new life,” which they claimed was only possible without “the remains of death in our teeth.” Keeping up with the times, the Bulgarian Tolstoyans enlisted new streams of thought in nutritional science, economics, and ecology in their effort to convince a mass audience beyond its narrow circles. Vegetarianism was offered as a solution to a range of social ills, including the pervasive violence and self-destruction that seemed to be bringing the modern world to the brink of extinction.

Many—though perhaps not all—of their arguments still ring true today. And yet, after a day of reading in the museum, I have to admit that I could not forgo a heaping plate of grilled kebabche — spiced meat patties — to accompany my glass of wine at a restaurant in nearby Sozopol. This region of Thrace, after all, was the ancient home to the cults of Orpheus and Bacchus. And as a historian and enthusiast of food, I had to partake of the local cuisine. And let’s not forget, that I was raised amidst the American cult of meat, in which meat was both seen as necessary protein source and the height of pleasure and leisure—just pull that burger off the barbeque and enjoy. This cult had clear (although distinct) echoes—my research had shown—behind the Iron Curtain. And yet, in both contexts—as globally—there were very locally situated anti-meat schools of thought. In this region those ideas and practices went back to ancient times, but were articulated most powerfully by the interwar Tolstoyans.

Also by Mary Neuburger on Not Even Past:

The Prague Spring Archive Project

Tobacco & Smoking in Bulgaria

The Museum of Sour Milk: History Lessons on Bulgarian Yoghurt

Cold War Smoke: Cigarettes Across Borders

Notes from the Field: From Feasts to Feats (or Feet) on the Coals

You may also like:

Sowing the Seeds of Communism: Corn Wars in the USA by Josephine Hill

Felipe Cruz reviews Banana Cultures: Agriculture, Consumption & Environmental Change in Honduras and the United States

Rebecca Johnston reviews The Man Who Loved Dogs

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.