For generations, race studies scholars—historians and literary critics alike—believed that race and its pernicious spawn racism were modern-day phenomena only. This is because race was originally defined in biological terms, and believed to be determined by skin color, physiognomy, and genetic inheritance. The more astute, however, came to realize race could also be a matter of cultural classification, as Ann Stoler’s study of the colonial Dutch East Indies makes plain:

“Race could never be a matter of physiology alone. Cultural competency in Dutch customs, a sense of ‘belonging’ in a Dutch cultural milieu . . . disaffiliation with things Javanese . . . domestic arrangements, parenting styles, and moral environment . . . were crucial to defining . . . who was to be considered European.”*

Yet even after we recognized that people could be racialized through cultural and social criteria—that race could be a social construction—the European Middle Ages was still seen as outside the history of race (I speak only of the European Middle Ages because I’m a euromedievalist—it’s up to others to discuss race in Islamic, Jewish, Asian, African, and American premodernities).

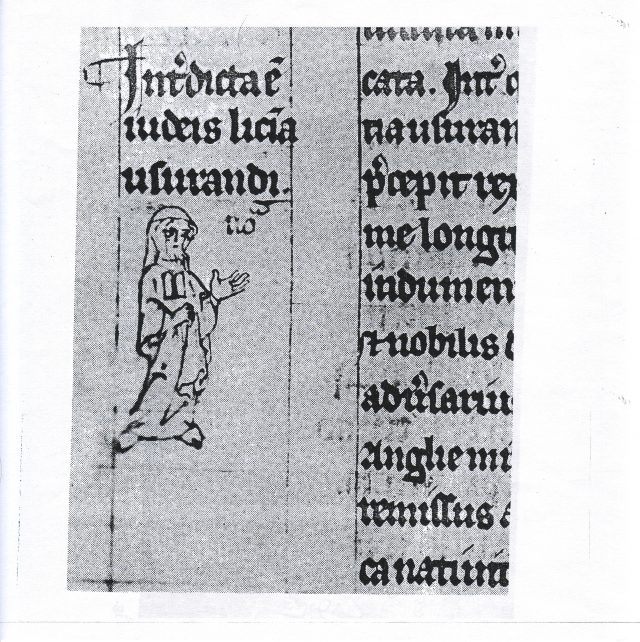

This meant that the atrocities of the Medieval Period—roughly 500-1500 CE—such as the periodic extermination of Jews in Europe, the demand that they mark their bodies and the bodies of their children with a large visible badge, the herding of Jews into specific towns in England, and the vilification of Jews for putatively possessing a fetid stench, a male menses, subhuman and bestial characteristics, and a congenital need to ingest the blood of Christian children whom they tortured and crucified to death — all these and more were considered to be just premodern “prejudice” and not acts of racism.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The exclusion of the medieval period from the history of race issues derives from an understanding of race that has been overly influenced by the era of scientific racism (in the so-called Age of Enlightenment), when science was the magisterial discourse of racial classification.

But today, in news media and public life, we see how religion also can function to classify people in absolute and fundamental ways. Muslims, for example, who hail from a diversity of ethno-races and national origins, have been talked about as if their religion somehow identified them as one homogenous people.

“Race” is one of the primary names we have for our repeating tendency to demarcate human beings through selected differences that are identified as absolute and fundamental, so as to distribute power differentially to human groups. In race-making, strategic essentialisms are posited and assigned through a variety of practices. Race is a structural relationship for the management of human differences.

Rather than oppose premodern “prejudice” to modern racisms, we can see the treatment of medieval Jews—including their legalized murder by the state on the basis of community rumors and lies—as racial acts, which today we might even call hate crimes, of a sanctioned and legalized kind. In this way, we would bear witness to the full meaning of actions and events in the medieval past, and understand that racial thinking, racial practices, and racial phenomena can occur before there’s a vocabulary to name them for what they are.

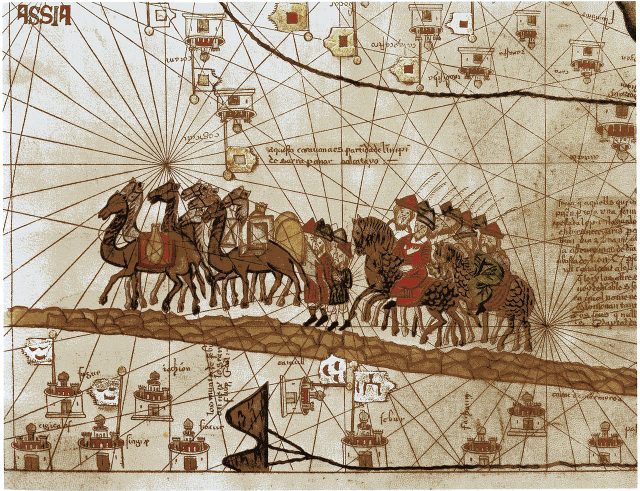

We can see medieval racial thinking in art and statuary, in maps, in saints’ lives, in state legislature, church laws, social institutions, popular beliefs, economic practices, war, settlement and colonization, religious treatises, and many kinds of literature, including travel accounts, ethnographies, romances, chronicles, letters, papal bulls, and more.

Accordingly, the treatment of Jews marks medieval England as the first racial state in the history of the West. Church and state laws produced surveillance, tagging, herding, incarceration, legal murder, and expulsion. A popular story of Jews killing Christian boys evolved over centuries, showing how changes in popular culture helped create the emerging communal identity of England. England’s 1275 Statute of Jewry even mandated residential segregation for Jews and Christians, inaugurating what would seem to be the beginning of the ghetto in Europe; and England’s expulsion of its Jews in 1290 marks the first permanent expulsion of Jews in Europe.

Similarly, Muslims in medieval Europe were transformed from military enemies into non-humans. The renowned theologian, Bernard of Clairvaux, who co-wrote the Rule for the Order of the Templars, announced that the killing of a Muslim wasn’t actually homicide, but malicide—the extermination of incarnated evil, not the killing of a person. Muslims, Islam, and the Prophet were vilified in numerous creative ways, and the extraterritorial incursions we call the Crusades coalesced into an indispensable template for Europe’s later colonial empires of the modern eras.

Even fellow Christians could be racialized. Literature justifying England’s colonization of Ireland in the twelfth century depicted the Irish as a quasi-human, savage, infantile, and bestial race—a racializing strategy in England’s colonial domination of Ireland that echoes from the medieval through the early modern period four centuries later.

The treatment of Africans in medieval Europe tracks the pathways by which whiteness ascended to primacy in defining Christian European identity from the mid-thirteenth century onward. Sub-Saharan Africans were grimly depicted as killers of John the Baptist and torturers of Christ in medieval art. Africa also allowed European literature to fantasize the outside world, and imagine what the world outside could offer—treasure, sex, wealth, supremacy—and consider how to make the rest of the world into something that better resembled Latin Christendom itself.

After Greenlanders and Icelanders encountered Native Americans in the early eleventh century, when the Norse founded settlements in North America, Icelandic sagas gleefully show the new colonists cheating Native Americans in exploitative trade relations half a millennium before Columbus. The colonists also kidnap two native boys and abduct them back to northern Europe, where the children are Christianized and taught Norse—an account of forced migration that may help explain why, among the races of the world today, the C1e DNA gene element is shared only by Icelanders and Native Americans.

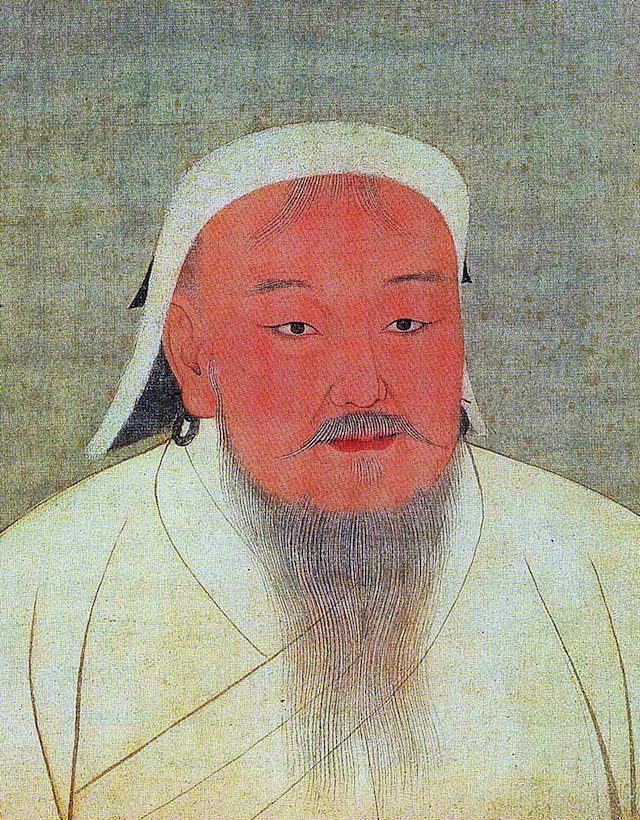

Europe’s evolving relationship with the Mongol race is traced in Franciscan missionary accounts, the famous narrative of Marco Polo and Rustichello of Pisa, Franciscan letters from China, the journey of a monk of the Church of the East from Beijing to Europe, and other travel narratives, that transform Mongols from a terrifying alien race into an object of desire for the West, once the Mongol imperium’s wealth, power, and resources became known. Mongols even offered a vision of modernity, of what that future might look like—with a postal express, disaster relief, social welfare, populace-maintained census data collection, independent women leaders, and universal paper money. Unlike the other races encountered by Latin Christendom—Jews, Muslims, Africans, Native Americans, and the Romani—Mongols were the only race representing absolute power to a fearful West.

Slavery in the medieval period was also configured by race: Caucasian slave women in Islamic Spain birthed sons and heirs for Arab Muslim rulers, including the famed Caliphs of Cordoba; the ranks of the slave dynasties of Turkic and Caucasian sultans and military elites in Mamluk Egypt were regularly resupplied by European, especially Italian slavers; and the Romani (“Gypsies”) in southeastern Europe became enslaved by religious houses and landowning elites who used Romani slaves as labor well into the modern era, making “Gypsy” the name of a slave race.

In the Middle Ages and today, it is the Romani—who consider themselves an ethnoracial group, despite considerable internal heterogeneity among their peoples—who best personify the paradox of race and racial identification. Romani self-identification as a race, despite substantial differences in the composition of their populations, suggests to us that racialization—by those outside, as well as by those who self-racialize—remains tenacious, well into the twenty-first century.

* Ann Laura Stoler, “Racial Histories and Their Regimes of Truth.” Political Power and Social Theory 11 (1997): 183-206

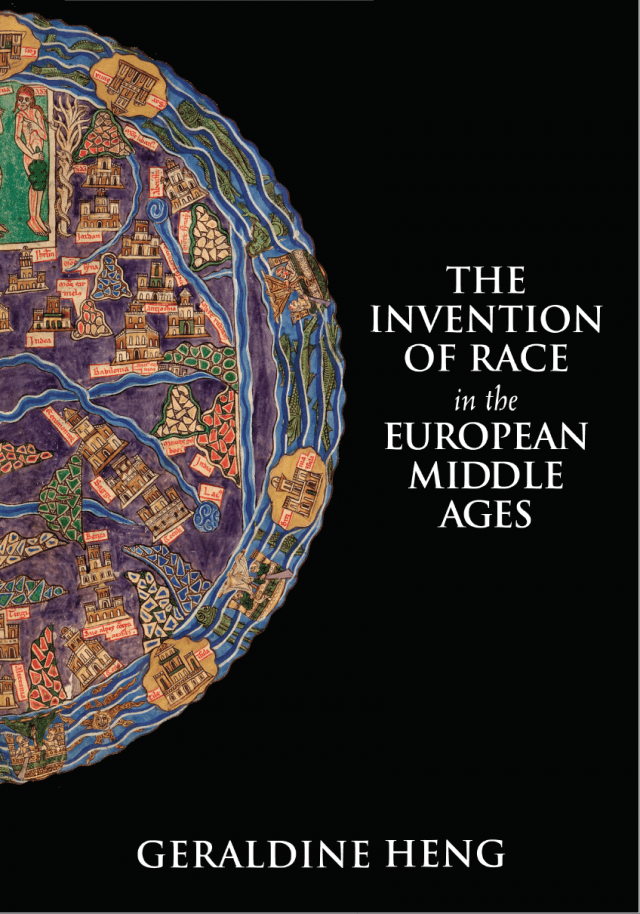

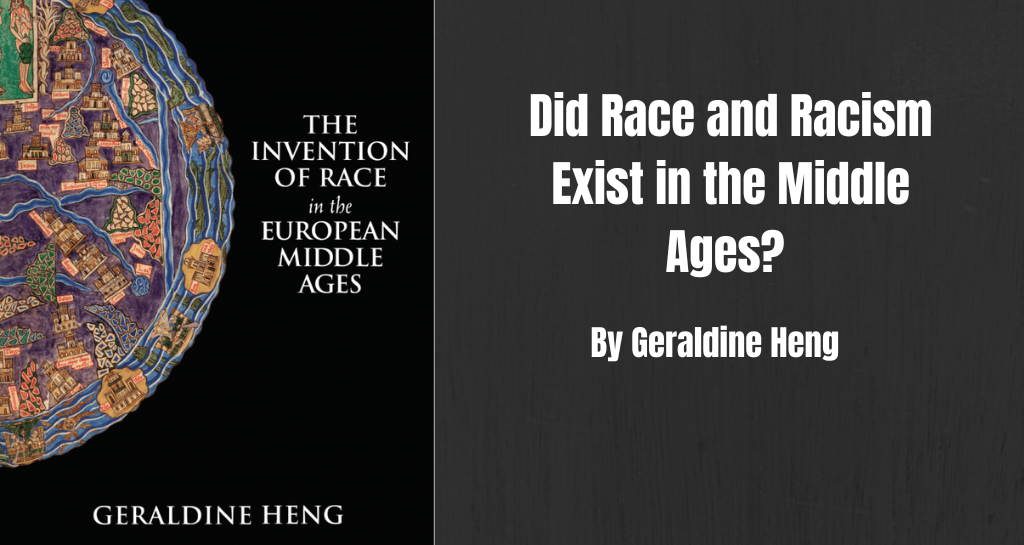

Geraldine Heng, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages

Recommended reading:

Madeline Caviness, “From the Self-Invention of the Whiteman in the Thirteenth Century to The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” Different Visions: A Journal of New Perspectives on Medieval Art 1 (2008).

A key study on the ascension of whiteness to centrality in European identity, as depicted in medieval art, with fifty-nine full-color images.

Jean Devisse, The Image of the Black in Western Art: From the Early Christian Era to the “Age of Discovery.” Trans. William G. Ryan. Vol. 2 Pt. 1: From the Demonic Threat to the Incarnation of Sainthood (2010).

An extraordinary, indispensable volume, with a vast collection of images of objects, illustrations, and architectural features depicting blackness and Africans in medieval European art. Part of an invaluable multi-volume series on blackness and Africans in art history, that ranges from antiquity to the modern period.

Ian Hancock, We are the Romani People (2002). A major study on the Romani, and Romani slavery, by a distinguished Romani studies scholar at the University of Texas in Austin.

Debra Higgs Strickland, Saracens, Demons, and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art (2003).

An important study showing us the implications of the iconography that visualized Jews, Muslims, Mongols, and monstrous humans for medieval audiences. Strickland reminds us that the human freaks depicted in art, cartography, and literature—often celebrated as wondrous and marvelous—shouldn’t teach us that medieval pleasure is pleasure of a simply and wholly innocent kind.

John V. Tolan, Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination (2002) and Sons of Ishmael: Muslims through European Eyes in the Middle Ages (2008).

Two indispensable studies on portrayals of Muslims in medieval Christian Europe.

Header image: Alexander encounters the headless people —Historia de preliis in French, BL Royal MS 15 E vi, c. 1445.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.