“Really! They have not even buried him yet!” This was my in-laws’ reaction to the two-hour, primetime special on Boris Nemtsov’s love life that aired the Sunday after his assassination. Nemtsov’s reputation as a “ladies man” was never a secret, but tarnishing his name just days after his death was too much, even for some people who disliked his politics.

When investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya was murdered in front of her Moscow building on October 7, 2006, I was shocked. I had read her work, discussed her in classes, and was even familiar with the street where she lived. However, discussions of the crime with Russian students and friends usually required me to explain what her work was about and why people in the West found her criticism of the war in Chechnya so compelling. Dozens of other Russian journalists and political activists have been murdered over the last decade, but the murder of Nemtsov is different.

When I came upon the news of Nemtsov’s murder two Friday nights ago, I immediately handed the iPad to my wife, and her jaw dropped. That Saturday morning, there was a pervasive shock — on Russian social media and in the state-run and independent media — because everyone knew Nemtsov. His political career in the 1990s included a post as Deputy Prime Minister in 1998 under Boris Yeltsin, and, before that, as Governor of the Nizhny Novgorod where he led agricultural and economic reforms. However, his liberalism often clashed with the former communist party members who made up much of the Russian government. More importantly, as corruption blossomed in the new Russian economy, he relentlessly attacked the perpetrators. His political career imploded because his idealism and activism had no place in the status quo Vladimir Putin created between society, the oligarchs and the state after 2000.

This is another reason why the murder shocked many Russians. Many people were perfectly happy to leave behind the idealistic politics and the mobster-political violence of the 1990s for Vladimir Putin’s Russia, which brought relative economic stability after the “wild” 1990s, even if it certainly did not ensure democracy. The fear of losing pensions or homes, as often happened in the 1990s, was and is much greater than the fear of authoritarian government. When Russian TV airs iconic 1990s mob movies such as Aleksei Balabanov’s Brother, people acknowledge the film’s greatness, but they are relieved that period of Russian history is behind them.

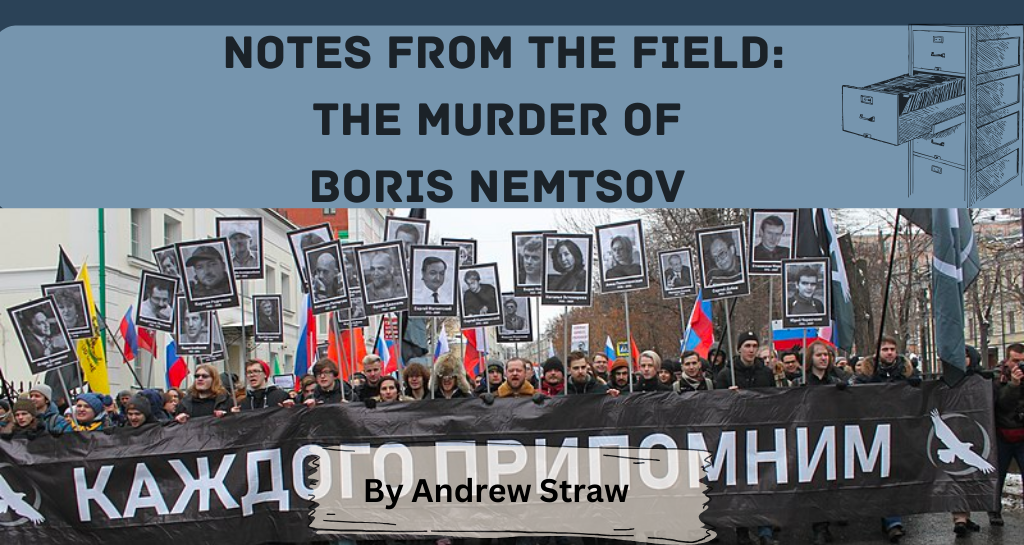

Moreover, perhaps more important than the symbolism of an opposition politician being murdered on the steps of Russian power, is what the public spaces around the Kremlin and in Central Moscow have come to represent for modern Muscovites. The Moscow city government, urban planners, and young activist politicians have spent the better part of the last decade transforming central Moscow into a more pedestrian friendly and livable urban space. Gorky Park has become a hipster paradise with hammocks, yoga, WIFI, and coffee shops. Many of the central streets (including the one Nemtsov strolled down on the night of his death) have been closed to traffic and lined with cafes. Red Square itself and the surrounding new pedestrian zones host numerous festivals and markets. This popular space to unwind has now become the scene of a brutal political murder.

Finally, with the war in Ukraine, Russian TV has been inundated with scenes of terrible and graphic violence, but the violence was quite far from Moscow. Now, with this backdrop, there is a sense that the inter-Slavic bloodletting that has been so far mostly confined to the Donbas could be reaching out to touch the Russian capital.

Even on my Facebook feed there were people who believed he got what he deserved. Still, the most common response I heard over the last week was of a dreaded return to the 1990s, when Russians, both politically important and ordinary citizens, did not feel safe in their homes, finances, jobs or city.

More by Andy Straw on Not Even Past

“The Tatars of Crimea: Ethnic Cleansing and Why History Matters“

“The 1980 Olympics and my Family“

_________________________________________________________________________________________

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Just as the demonstrations were winding down, this group of young women, dressed in boldly colored dresses and tights, and masking their faces with equally bright balaclavas, or ski masks,

Just as the demonstrations were winding down, this group of young women, dressed in boldly colored dresses and tights, and masking their faces with equally bright balaclavas, or ski masks,