Kristie Flannery’s groundbreaking first book, Piracy and the Making of the Spanish Pacific World is not only about how Spanish colonial rule worked in the Philippine Islands. Rather, Piracy and the Making of the Spanish Pacific World analyzes how colonialism, forms of capitalism, and religion forged political, economic, and religious alliances across Asia, the Americas, and Europe. This research reveals that colonialism in the Philippines was a process that went beyond the boundaries of the islands. The book shows that globalization and European imperial expansion influenced how ideas and actions traveled through the Spanish Empire in specific places or vast spaces such as the Pacific Ocean.

Flannery invites readers to explore the ways in which societies are structured. The book recovers forgotten stories of Indigenous soldiers and migrants who struggled to restore their identities when they were arbitrarily and constantly changed. Piracy serves as the central theme in the book and functions as the axis from which the real or imaginary fears that threatened the loyalties established between the inhabitants of the Philippines and the Spanish empire in Asia revolve. Piracy works as a driver of alliances between social groups and as an excuse to impose a regime of violence and genocide on an unwanted migrant population. This book examines how violence, piracy, imperial loyalties, and concepts of identity shifted and remained ambivalent, shaped by the actions of people and the fears—both real and imagined—that arose in a globalized imperial world.

Much of the conceptual support of this book revolves around key notions such as loyalty, identity, and violence. These categories of analysis are fundamental to understanding how subjects were classified in the colonial system using terms that were incorporated so deeply that they survived even the disappearance of the Spanish empire. In other words, this conceptual framework sheds light on why it is relevant to understand the motivations that compelled people to exercise acts of discrimination and violence against Muslim and Filipino subjects. Some policies of discrimination witnessed and exercised during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries could be interpreted as political strategies to exploit and segregate people from China, creating a system of social control that was both tangible and intangible– or in the words of the author, both real and imaginary.

The methodological challenge of this book is contained in the possibility of archival research also of a global order. Kristie Flannery draws from Asian, Latin American, and Spanish archives in cities such as Manila, Seville, Mexico, and London among others, and integrates an extensive multilingual corpus of documents. By intersecting sources and exploring seemingly disconnected materials, the methodology expands into a spatial and scalar approach. This approach enables an ambitious exploration of riverine, maritime, and land connections, as well as the barriers between them. Each chapter begins with the departure or arrival of a ship that also represents a way of venturing into history in a fluid way to read a historical moment where real and imaginary piracy contributed to the Spanish colonial order in the Philippines.

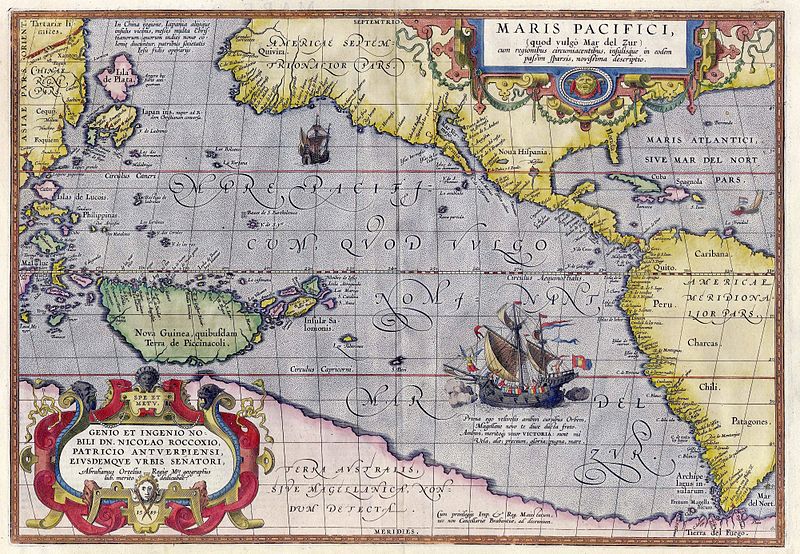

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The book is composed of five chapters, an introduction, and an epilogue. Chapter 1, set in the eighteenth century, explores how the ideas of Muslims and Islam from the Mediterranean shaped Spanish strategies in the Americas and the Philippines, influencing defense strategies against Moorish piracy and later creating alliances between various actors according to their notions of religion and loyalty. This is a fascinating chapter in which identity and loyalty are central to understanding that the Spanish empire did not always reach all corners in the same ways.

Chapter 2 explores how the fluctuating threats of Mora piracy impacted the transient Chinese population, who settled far beyond the shores of Manila. The threats of pirate fleets reveal how the massacres of the Chinese population in 1603, 1639, and 1662 in the Philippines created an environment where religion was the engine of waves of violence and that ended up pushing alliances of the Sangleyes (referring to the Chinese migrants in the Philippines) in Manila as faithful vassals.

Chapters 3 and 4 delve into the invasions of Manila during the eighteenth century, showing how indigenous Filipinos challenged loyalties to face the arrival of the British by showing strong local opposition. And then Flannery analyzes how Spanish rule was restored by confronting the British invasions and also the local insurgents. Finally, Chapter 5 shows how migrants born in China after the war were collectively expelled from Manila and the forms of resistance these migrants used to confront an expulsion.

In general terms, I identify several substantial contributions of this research to the study of imperial colonial historiography and the Spanish Pacific. First, the analysis of the history of piracy in the Spanish Pacific offers an understanding of how Spanish forms of government and colonial authority were adaptable to different contexts. In other words, there is not a single, uniform way of understanding the Spanish empire in the Americas and in the Philippines. Instead, there are intermediate positions, in this case, mediated by alliances, which must also be considered in the historiography. These individuals played active roles in shaping history and provide new perspectives for reinterpreting traditional historical narratives.

Second, forms of violence during this period continue to be fundamental elements in understanding how notions of identity and understanding of the “other” as alien to one’s own materialized. In addition, they were motivated by religious and political discourses that were also transoceanic. That is, ideas and actions also traveled with people. Third, this research carefully highlights how the Spanish empire classified colonial subjects based on race, social status, and religion and created policies of exclusion that were used to subvert an order according to real or imagined motivations that people had. This research shows that forms of social differentiation also can be inherited. Perhaps, this is why it is so important for Flannery to show how colonial and early modern ideas and practices persist and influence the ways we see each other and our world today. This is a carefully structured book with a geographical richness to enjoy. A book that becomes part of the field of colonial studies with a fascinating vision of a space sometimes forgotten by historiography: the Pacific.

Cindia Arango López. Historian, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellín. Mg. in Geography, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá. Specialist in Environment and Geoinformatics: SIG, Universidad de Antioquia. Currently, PhD student in Latin American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, TX-USA. She has been a professor of the undergraduate program in Territorial Development at Universidad de Antioquia, Oriente campus, Colombia. Currently, she is developing her candidacy for her doctoral research on the navigators bogas of the Magdalena River in the 18th century in Colombia.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

by

by