Last Thursday, the Polish senate passed a bill that would outlaw public statements that acscribe responsibility or complicity to the Polish nation or state in crimes committed by Nazi Germany during the Second World War. If signed into law by President Anrzej Duda, who supports the measure, using terms like “Polish Death Camp” would become punishable by fines or jail time up to 3 years. “The point I must stress most emphatically is that there was no complicity in the Holocaust,” explained Duda in a statement, “either on the part of Poland as a state, a non-existent state, or on the part of Poles perceived as a Nation.”

The pending legislation has prompted a diplomatic spat with Israel and is considered an “attempt to rewrite history” by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The U.S. State Department has also expressed disapproval, citing concerns over the potential strains on Poland’s relationship with the U.S. and Israel, as well as freedom of speech.

Around the same time, state-owned Polish Radio (Polskie Radio) launched an interactive website “aimed at debunking misconceptions about Poland’s role in the Holocaust,” according to a release. The site is available in Polish, English, and German.

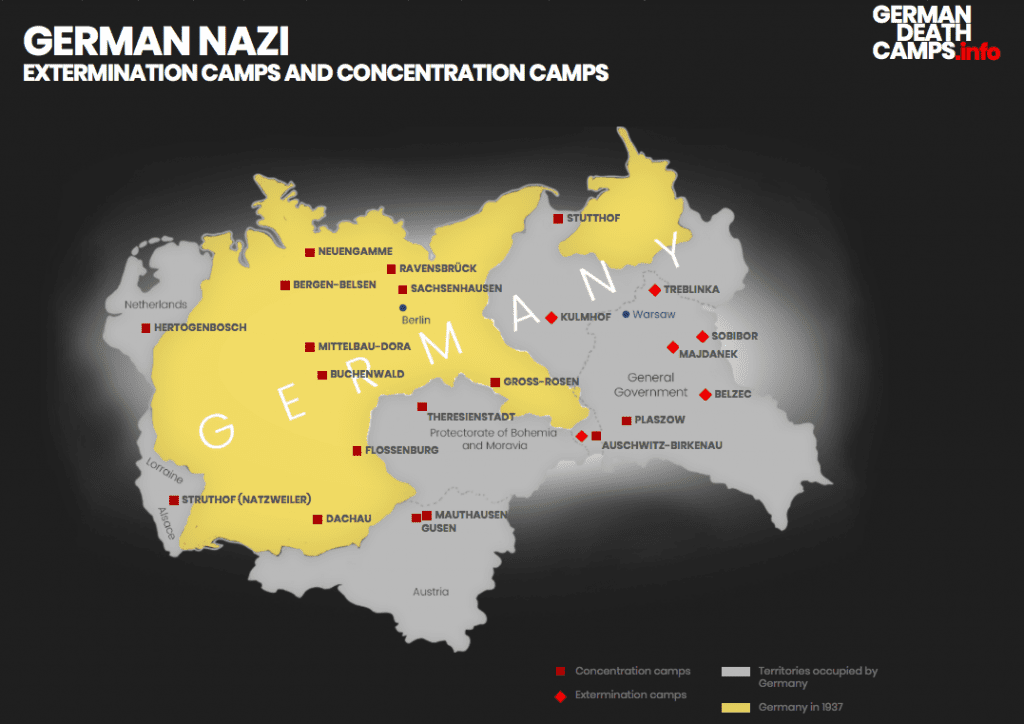

Titled “Germandeathcamps.info,” the first section shows a map of the Nazi camp network established across occupied Europe, followed by thematic sections including profiles of German perpetrators, a short timeline of the Final Solution, video footage of the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials, and oral histories of victims. The last section, titled “distortion of history,” refers to two cases of the usage of “Polish death camps” in the recent past – once by German broadcasting company ZDF and by President Obama in a 2012 speech.

This public history project has a clear political agenda – that is, to show that camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau were Nazi, not Polish, camps, and thus attest that the Polish state bore no responsibility for complicity in the Holocaust. Opponents agree that the term “Polish death camps” is indeed inaccurate, but worry that the law would silence instances when Poles were culpable in Jewish persecution, whether by aiding local German authorities in rounding up their Jewish neighbors, denunciation, or, in some cases, killing. In a joint statement issued by the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews and the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland, Dariusz Stola and Piotr Wiślicki warned of a chilling effect in difficult discussions of crimes committed on Polish soil, calling for honest and open discussion.

The larger implications of a law banning the suggestion of Polish complicity is much larger than simple phraseology. Distilling the conversation into categories of “collaborator” and “victim” precludes a more difficult public conversation on the wide range of actions, experiences, and responses on part of gentile Poles in relation to the persecution of Jews during the war. Poles were victims of Nazi persecution, as they were also helpers, rescuers, and participants, and their motivations as such were complex and contradictory in ways that defy easy categorization. Two major studies illustrate this complexity.

Jan T. Gross’ Neighbors intensified the debate about Polish “complicity” in the Holocaust. Neighbors tells the story of how on one day in July 1941 a group of Polish residents in Jedwabne murdered 1,600 of their Jewish neighbors, about half of the population. According to Gross, it was Poles who did the killing, not the local German gendarmes. At a time when Poland’s national self-image of WWII was, and is, one of victimhood, the revelation of an instance in which Poles had brutally murdered their Jewish neighbors stirred a debate about “complicity” and “collaboration” that, as the proposed law might suggest, has not yet been resolved.

In Hunt for the Jews: Betrayal and Murder in Occupied Poland, Jan Grabowski recounts the role of Poles in the rounding up and murder of Jews in Dabrowa Tarnowska, a county in southeast Poland. After the ghettoes in the area were liquidated in 1942, Germans relied on local Poles to hunt Jews (referred to as Judenjagd) who had escaped liquidation and hid among the gentile population or in the forest. The Polish Blue Police, the Baudienst, and local Polish peasants played an active role in denouncing Jews, participating in searches, or even killing. Jewish property was often a motivation for participating, as the Germans instituted a reward system. Importantly, there are also many instances of rescue: some Poles hid Jews from the Nazis, and their motivations for doing so varied, sometimes altruistic, sometimes materially-driven. Sometimes, if the hidden Jews were no longer able to compensate their Polish hosts, they were denounced to the local authorities.

The Polish state does not share some kind of equal “co-responsibility” with the Nazis (the state was actually in exile in London), because the Germans were the “undisputed bosses of life and death” in occupied Poland, as Gross argues, and “no sustained organized activity could take place without their consent.” Even if the law emphasizes the role of the Polish state, the law seems to be a pretext to stifle the discussion of the participation of Polish people, as seen in Jedwabne and Dabrowa Tarnowska. As works like Neighbors argue, we must account for the Holocaust both as a system of mass murder and also for its discrete episodes of impromptu violence carried out by local people. It is also important to note that Polish responses, actions, and attitudes are not easily distilled into categories like “collaborator,” “bystander,” or even “victim,” it is possible that individuals can be any or all three of these things to different extents, at different points in time, and for different reasons. Allowing space for honest, evidence-based discussion is vital to this kind of constructive engagement with difficult pasts, which has already been taken on by several Polish scholars and institutions. As these voices in Poland urge, ignorance is best challenged through education, not silence.

Also by Natalie Cincotta on Not Even Past:

Review of Blitzed: Drugs in the Third Reich by Norman Ohler

Review of Veiled Empire: Gender and Power in Soviet Central Asia

Virtual Auschwitz by David Crew

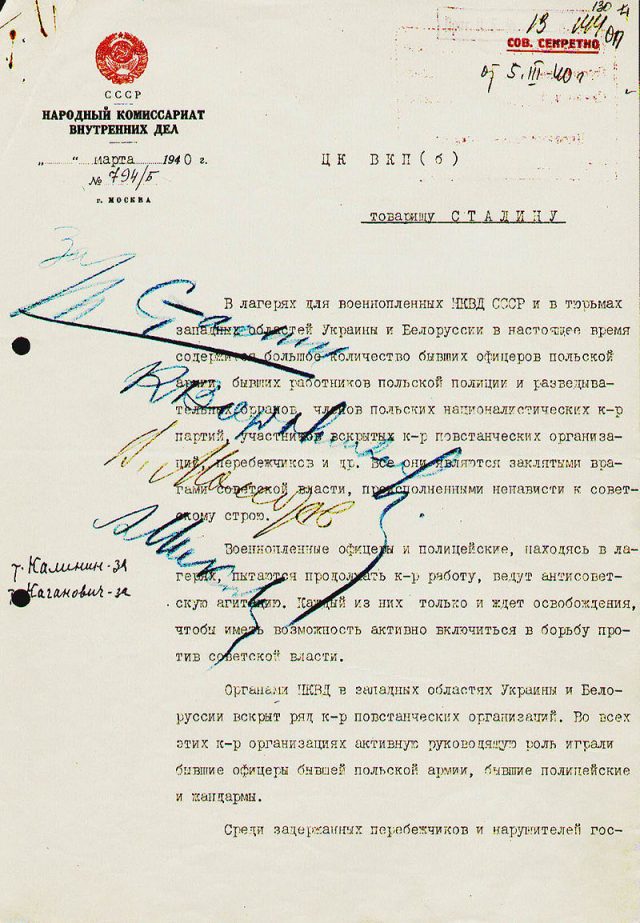

Looking into the Katyn Massacre by Volha Dorman

David Crew reviews The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939-1945 by Saul Friedländer

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.