By Jimena Perry

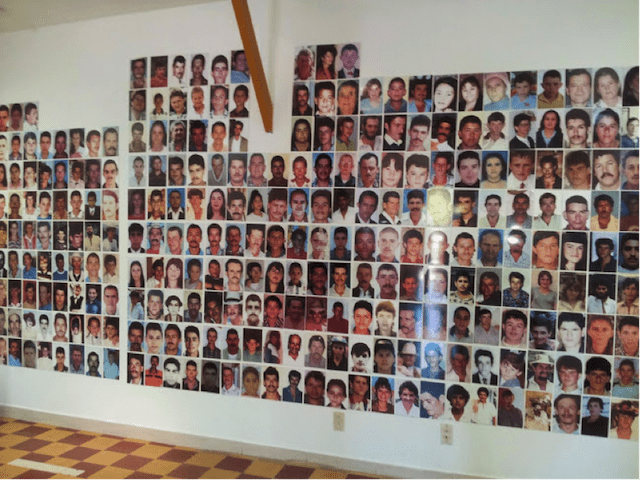

During the summer of 2014 I had the chance to visit the Hall of Never Again (El Salón del Nunca Más) in the Department of Antioquia, in northwest Colombia. What started just as a tourist visit soon became a research interest. Growing up in a country overwhelmed by an ongoing armed conflict, the Hall made quite a huge impression on me due to the visual narrative it contained. Photographs of the faces of approximately180 victims of the violence are displayed on a wall to highlight a history in which the victim’s voices are privileged. It was quite different from the discourses shaped by state institutions such as the National Museum of Colombia that feature official histories about national identity and citizenship. These contrasting accounts of recent brutalities in Colombia made me want to explore the ways that individuals and communities remember their violent pasts. Grieving, as part of a remembrance process, has no handbook and no formulas; it is not a unilinear process. It is complex and ongoing. Grief and memories of violence are informed by history and culture and require to be understood as a social dynamic practice.

During the summer of 2014 I had the chance to visit the Hall of Never Again (El Salón del Nunca Más) in the Department of Antioquia, in northwest Colombia. What started just as a tourist visit soon became a research interest. Growing up in a country overwhelmed by an ongoing armed conflict, the Hall made quite a huge impression on me due to the visual narrative it contained. Photographs of the faces of approximately180 victims of the violence are displayed on a wall to highlight a history in which the victim’s voices are privileged. It was quite different from the discourses shaped by state institutions such as the National Museum of Colombia that feature official histories about national identity and citizenship. These contrasting accounts of recent brutalities in Colombia made me want to explore the ways that individuals and communities remember their violent pasts. Grieving, as part of a remembrance process, has no handbook and no formulas; it is not a unilinear process. It is complex and ongoing. Grief and memories of violence are informed by history and culture and require to be understood as a social dynamic practice.

The Colombian violence of the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s, the subject of my work, left many victims. It also left many survivors of atrocities who needed some kind of closure in order to continue with their lives. During these decades, civilians found themselves caught among four armed actors: the National Army, paramilitaries, guerrillas, and drug lords, who were fighting over the control of land and civilians. These groups committed brutalities such as kidnappings, disappearances, forced displacement, bombings, massacres, and targeted murders. In order to cope with and overcome the trauma caused by all this violence, diverse communities set up museums and displays. These acts of memory and reconciliation demonstrate that people and communities remember and represent the past differently. Some exhibitions portray violence, others focus on personal histories and others turn to the strength their cultural traditions give them. They contain different meanings and intentions, and take a variety of forms including traveling museums, murals, houses, kiosks, and even cemeteries devoted to remembering the ones who are gone. But they all work towards the same goal: never again.

My interest in studying historical representations of violence was sparked when I realized that in Colombia, memories about the atrocities of the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s are quite diverse and do not appear in state institutions. I also came to understand that although grieving has a place for the reconstruction of facts and a search for “truth,” these are not the most important aspects for individuals and communities. After talking with community leaders and reading the scholarship on memory and museums, I can say that instead of truth quests people want to feel that their absent loved ones are not forgotten, that their lives meant something.

Part of the attention that communities are devoting to the production of historical memories of violence is closely related to the diverse healing processes grounded in local cultures. The rural memory venues I am researching emphasize local traditions, beliefs, and patterns of behavior. Their displays illustrate how violence altered their way of life and how individuals and groups are coping with new realities, silences, and absences. Culture becomes a cohesive factor, the resource communities appeal to in order to heal and envision a future.

Therefore, my research has two major parts. First, it relies on ethnographic descriptions of the memory sites and the violent episodes they are representing. Second, these memories of violence help me analyze how contemporary citizenship is understood in Colombia, as rooted in these communities’ struggles with the violence past

And my research has a third component—public history. Writing and researching about memory venues in Colombia is my way of helping in the healing of local communities. My wish is that my work will help people feel that their histories are not forgotten and that they are an inspiration for generations to come.

I also want my writing about memory venues in Colombia to contribute to a new, more diverse, sense of national identity. I want the narratives portrayed in these venues to be incorporated into a national discourse. One of my hopes is that by reading about the testimonies and descriptions about recent Colombian violence in local memory projects, the general public can go beyond the gory details about violence and remember the victims as living family and community members, and as part of the Colombian community. My aspiration is that the diverse Colombian voices become part of the project of nation-state building. Everybody talks about the importance of respecting and understanding other ways of seeing the world, but when it comes down to concrete political actions, alterity is often ignored.

You may also like these articles by Jimena Perry on two museums that represent the Colombian violence since the 1960s: the Hall of Never Again, a community-led memory museum in Colombia, and The Center for Memory, Peace, and Reconciliation, Bogotá, Colombia