This new series features five online museum exhibits created by undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin for a class titled “Colonial Latin America Through Objects.” The class assumes that Latin America was never a continent onto itself. The course also insists that objects document the nature of historical change in ways written archives alone cannot.

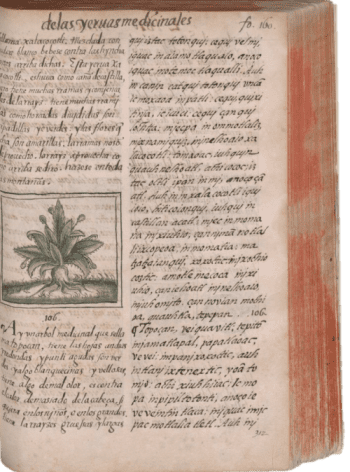

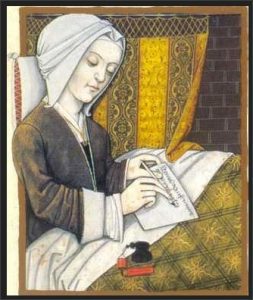

Diana Heredia López’s exhibit centers on the Florentine Codex, a twelve volume encyclopedia of Aztec knowledge compiled by Franciscan friars and dozens of Nahua scribes trained in the mid sixteenth century in in Latin and classical learning. These polyglot Indians surveyed the natural history of central Mexico using Pliny’s model. The latter described objects along the ways they were processed, consumed, and transformed. She focuses on Nahua agave, cotton, figs, and gourds and the fabrics and containers they engendered.