This review was originally published on the Imperial & Global Forum on May 22, 2017.

By Ben Holmes (University of Exeter)

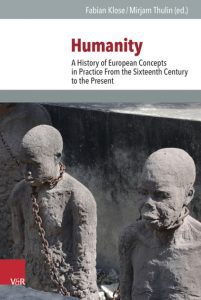

What does it mean to belong to the human race? Does this belonging bring with it particular rights as well as responsibilities? What does it mean to act with humanity? These are some of the big questions lying at the heart of a new edited collection from Fabian Klose and Mirjam Thulin, Humanity: A History of European Concepts in Practice From the Sixteenth Century to the Present (2016). Based on a 2015 conference at the Leibniz Institute in Mainz, the book, as the title suggests, is not a purely conceptual history of the term “humanity.”[1] Rather it looks to discover “the concrete implications of theoretical discourses on the concept of humanity.” In other words, how did ideas of “humanity” guide European practices in areas like humanism, imperialism, international law, humanitarianism, and human rights?[2] The editors argue that despite the implied timeless, universal nature of the term, humanity is both a changing, dynamic concept, and has been prone to create divisions as much as it promotes commonality. Although the volume is a study of European conceptions of humanity, the contributions are transnational, displaying how conceptions of humanity were practiced in Europe and in the continent’s interactions with the wider world over the course of five-hundred years.

What does it mean to belong to the human race? Does this belonging bring with it particular rights as well as responsibilities? What does it mean to act with humanity? These are some of the big questions lying at the heart of a new edited collection from Fabian Klose and Mirjam Thulin, Humanity: A History of European Concepts in Practice From the Sixteenth Century to the Present (2016). Based on a 2015 conference at the Leibniz Institute in Mainz, the book, as the title suggests, is not a purely conceptual history of the term “humanity.”[1] Rather it looks to discover “the concrete implications of theoretical discourses on the concept of humanity.” In other words, how did ideas of “humanity” guide European practices in areas like humanism, imperialism, international law, humanitarianism, and human rights?[2] The editors argue that despite the implied timeless, universal nature of the term, humanity is both a changing, dynamic concept, and has been prone to create divisions as much as it promotes commonality. Although the volume is a study of European conceptions of humanity, the contributions are transnational, displaying how conceptions of humanity were practiced in Europe and in the continent’s interactions with the wider world over the course of five-hundred years.

The volume is divided into four sections. The two chapters in section one explore how ideas of humanity developed over the volume’s five-hundred year period. Francisco Bethencourt demonstrates how, since antiquity, ideas of the humanity or sub-humanity of different categories of people have created legal and political divisions between the rights of free man and slave, civilized and barbarian, or man and woman. Although these distinctions have gradually eroded in response to more inclusive notions of humanity, Bethencourt warns that hierarchical ranking of peoples remains “one of the persistent realities of [the] human condition,” thus disabusing “triumphalist narratives” which would portray modern notions of “humanity” as the culmination of an inevitable progress of enlightened beneficence.[3] Paul Betts looks more closely at the politicization of humanity during the twentieth century. He also shows humanity was not the sole property of progressive politics; throughout the century “humanity remained a slippery term, and could be aligned to various causes,” including fascist, communist, or racist ones which legitimated what many would consider inhuman practices like apartheid. Betts provocatively concludes by suggesting that an intellectual estrangement exists between the aspirational notions of common humanity today and those notions that characterized previous generations of internationalists.

The rest of the chapters in the book are structured according to what the editors describe as”‘three essential areas” that constitute sub-topics of humanity. Thus, Part II revolves around the development of ideas and debates surrounding morality and human dignity in the context of major transnational movements like humanism, colonialism, or missionary activity. Compared to the later sections, some of the chapters in Section II study humanity in a slightly more theoretical fashion than as a “concept in practice.” Mihai-D. Grigore’s chapter situates Desiderius Erasmus’s (1466-1536) sixteenth-century political writings as emblematic of a wider transition from theological to political understandings of humanity, and Mariano Delgado’s chapter presents the Spanish Franciscan friar Bartolmé de Las Casas’s (1484-1566) arguments for recognizing the humanity of indigenous populations of Spain’s “New World.” In doing so, they provide a study of the changing ideological conceptions of humanity rather the practical implications of these ideas. This should not detract from two very useful case studies of sixteenth-century debates about human nature; but it does raise the question of how far one pushes the idea of a “concept in practice” In contrast, Judith Becker’s contribution on nineteenth-century German Protestantism in India illustrates the practical implications of ideas of humanity by showing how the missionaries’ belief in the unity of mankind guided both the evangelistic and humanitarian aspects of their missionary work in India.

Portrait of Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1523 (via Wikimedia Commons).

Section III examines themes around humanitarianism, violence, and international law, and illustrates how theories of humanity practically affected European attempts to remedy or restrain the violence of warfare or slavery. Thomas Weller provides an intriguing case study on the contributions the sixteenth-century Hispanophone world made to the arguments later famously espoused by eighteenth-century Anglo-American abolitionists in their protests against the transatlantic slave trade. While questioning any straightforward evolution between the arguments of sixteenth-century writers like Tomás de Mercado (1525–1575) or Luis de Molina (1535-1600) and eighteenth-century transatlantic abolitionists like William Wilberforce (1759-1833), Weller does highlight an under-researched topic concerning what he considers “humanitarianism before humanitarianism.” Picking up the antislavery story, Fabian Klose shows that while British abolitionist narratives about African humanity helped shape the national and international legislation that ended the transatlantic slave trade, these same appeals to protect humanity also legitimated new forms of violence, like armed intervention and colonial expansion in order to enforce the ban. Further emphasizing that the relationship between humanity and humanitarianism is far from straightforward, Esther Möller shows the tensions over the concept in the Red Cross Movement in the second half of the twentieth century. Specifically, the implementation of humanity as the first of the seven Fundamental Principles of the Red Cross precipitated debates in the movement between those who saw humanity as a politically neutral concept, and those national societies involved in anti-colonial struggles, which argued that engagement with politics was a humanitarian duty. Humanity, intended as a principle to unite national societies, actually highlighted the regional and political divisions in the movement.

The final section focuses on how humanity has influenced social and benevolent practices like charity, philanthropy, and solidarity movements. Picking up the themes of Möller’s chapter, Joachim Berger shows the difficulties of using humanity as a rhetorical device to unite a transnational movement like international Freemasonry. In international forums for European Freemasons, humanity acted as an “empty signifier” which papered over national differences, but these regional differences were re-exposed whenever practical action to support “universal brotherhood,” like transnational charity, was proposed. Studying nineteenth century Catholic philanthropic groups’ promotional campaigns for child-relief in Africa and Asia, Katharina Stornig highlights the at-times dissonant nature of European conceptions of humanity. These philanthropic campaigns used universalist rhetoric of a common humanity to present a moral imperative to save distant children, while simultaneously emphasizing the “barbarity” and “inhumanity” of these children’s parents, who they deemed responsible for this suffering. Gerhard Kruip’s chapter, using church documents to explore the Catholic Church’s attitudes towards solidarity and justice, is part history and part call-to-arms. Kruip exhorts the current Catholic hierarchy to do more to promote global justice by becoming less western-centric, less centralized, “and more open to all the different cultures of the human family,” while also calling for greater state regulation and collective action to ensure a fairer distribution of “common goods for humanity as a whole.”

Johannes Paulmann concludes the volume by tying the big themes together with his four main perceptions on humanity. Firstly, humanity has often been defined by its antonyms, most obviously by behaviors of inhumanity. Secondly, the abstract nature of humanity allowed the concept to fulfill a diverse array of functions for a multiplicity of causes. Paulmann’s third and fourth perceptions question the static nature and universality of humanity. Not only was humanity dynamic, which its proponents often understood as a process and goal rather than a fixed reality, but many of these ideas of ‘progress’ implied notions of hierarchies in terms of civilization or development. Paulmann’s conclusion provides a welcome theoretical summary, bringing together the volume’s diverse collection of topics.

The volume’s scale and scope will make this book attractive to scholars of humanitarianism, international law, and human rights. The structure of the volume, while generally clear, could have been explained in more depth for the benefit of non-specialists. For instance, dividing humanitarianism and charity into two separate sections may require clarification to anyone unfamiliar with the theoretical difference between the two. Moreover, some chapters occasionally skirted between themes of humanitarianism, charity, and missionary, which created a bit of confusion. Nevertheless, this is a very important collection of case studies exploring the European concept of humanity and its spread, and leaves the door open to future works focusing on non-European conceptions of the term and how non-Europeans may have actively re-shaped and reinterpreted European ideas.

![]()

[1] For such histories, see Hans Erich Bödeker, ‘Menscheit, Humanitӓt, Humanismus’, in Otto Brunnter et. al. (eds.) Geschtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen in Deutschland vol.3 (Stuttgart, 1982).

[2] A vast corpus of works exist on each of these areas, which are too many to list here. For humanitarianism see Michael Barnett, Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism (Ithaca, 2011). For humanitarianism’s relationship with imperialism see Rob Skinner and Alan Lester, ‘Humanitarianism and Empire: New Research Agendas’, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 40:2 (2012), 729-747. On human rights see Stefan-Ludwig Hoffman (ed.), Human Rights in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, 2011).

[3] For more criticism on ‘triumphalist narratives’ of human rights see Samuel Moyn, The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History (London, 2012).

The Price for Their Pound of Flesh, by Daina Ramey Berry

Walter Benjamin on Divine Violence, by Joshua Abraham Kopin

Age of Anger: A History of the Present, by Pankaj Mishra (2017), reviewed by Ben Weiss

![]()