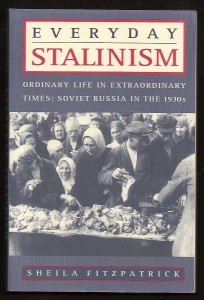

Leonardo Padura is arguably one of Cuba’s most untouchable writers. He made his name first as an investigative journalist, and then as the author of the Havana Quartet detective series, sometimes described as “morality tales for the post-Soviet era.” The Man Who Loved Dogs is by far his most ambitious work. A painstakingly-researched historical novel, it is the culmination of Padura’s twenty-year journey, beginning at the final home of Soviet exile Leon Trotsky in Coyoacan, Mexico and concluding with the National Prize for Literature, Cuba’s highest literary honor. It has received nearly universal critical praise, with the bemusing exception of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Their dissatisfaction may have stemmed from the premise in their review that Padura’s book is about “why revolutions and revolutionaries fail,” which it is not.

Leonardo Padura is arguably one of Cuba’s most untouchable writers. He made his name first as an investigative journalist, and then as the author of the Havana Quartet detective series, sometimes described as “morality tales for the post-Soviet era.” The Man Who Loved Dogs is by far his most ambitious work. A painstakingly-researched historical novel, it is the culmination of Padura’s twenty-year journey, beginning at the final home of Soviet exile Leon Trotsky in Coyoacan, Mexico and concluding with the National Prize for Literature, Cuba’s highest literary honor. It has received nearly universal critical praise, with the bemusing exception of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Their dissatisfaction may have stemmed from the premise in their review that Padura’s book is about “why revolutions and revolutionaries fail,” which it is not.

The Man Who Loved Dogs is largely a novel about struggle. The complex narrative follows the lives of three protagonists, one of whom is also the narrator, across two continents and several decades. The first, Leon Trotsky, struggles to remain politically relevant after his exile from the Soviet Union in 1929, fighting to maintain an alternative to Stalin’s form of communism through his global opposition movement and the Fourth International. Next is Spanish revolutionary Ramón Mercader, struggling to defend the ideals handed down to him from Moscow, pledging unwavering obedience first to his radical Marxist lover África, then to his sociopathic mother Caridad, and finally to a coercive state bureaucracy. Finally, the narrator, Iván Cárdenas Maturell, struggles to survive the reconstitutive process by which Fidel Castro’s Cuban government seeks to shape him into the “New Soviet Man.” The novel subjects Iván to a series of “falls,” one after another, until, as he puts it, “they fucked me for the rest of my life.” Throughout the book, all three protagonists struggle to come to terms with their actions, to determine who they are, and what meaning their lives may have had.

All of this struggle raises the question of what it is that the characters are struggling for. At times, the fight seems to be an end in and of itself, something the characters often seem aware of. Ramón joins the Republican Army in the Spanish Civil War, “convinced that his life only had meaning if he was able to defend with a rifle the ideas in which he believed.” At the same time, those ideals “had been only recently discovered by many,” and yet he and those around him had “prepared themselves for sacrifice.” Trotsky’s first wife, Alexandra Sokolovskaya, lays the death of their daughter at Trotsky’s feet, “accusing him of having marginalized Zinushka from the political struggle and of having thus pushed her to her death.” For Sokolovskaya, denying Zina a role in that battle was more deadly than the tuberculosis consuming her lungs. For each of them, struggle itself was a method of survival.

There are external motivations for these struggles as well. On accepting a Jason Bourne-style pact, the Soviet government transforms Ramón into Soldier 13, an entity that “did what they asked him to out of obedience and conviction.” Indeed, the importance of obedience dominates Ramón’s entire political career. Early on, África makes it clear to him that the Party is always right and obedience to the Party is mandatory, even though you may never understand the Party. Similarly, Iván’s rise from his falls was contingent on obedience to the Party line. He is given continual “correctives” until his writing falls within the acceptable standards set for him by the Cuban government, itself obeying the order to adopt them from the Soviet model.

Central to both these instances of obedience, and key to understanding the book, is a denial of access to knowledge. When Iván speaks with his friend Dany about conducting research on Trotsky, Dany emphasizes the inherent danger of particular forms of knowledge. “I’m not going to become a Trotskyist or any shit like that,” Iván spits in defense. “What I need is to know…k-n-o-w, you get it? Or is it also forbidden to know?” To which Dany replies: “But you already know that Trotsky is fire!” Any type of knowledge that falls outside the Party line is potentially deadly. As a writer and radio worker, Iván is responsible for propagandizing the “correct” form of knowledge, making his transgression even more dangerous than that of a typical citizen. While Iván is coerced to shun any knowledge of Trotsky, Ramón is called upon to eliminate him in the most literal fashion. He accepts the Soviet government’s “first sacred principle: obedience,” allowing himself to be denied an understanding of truth, and ultimately destroying this alternative interpreter and propagandizer of knowledge.

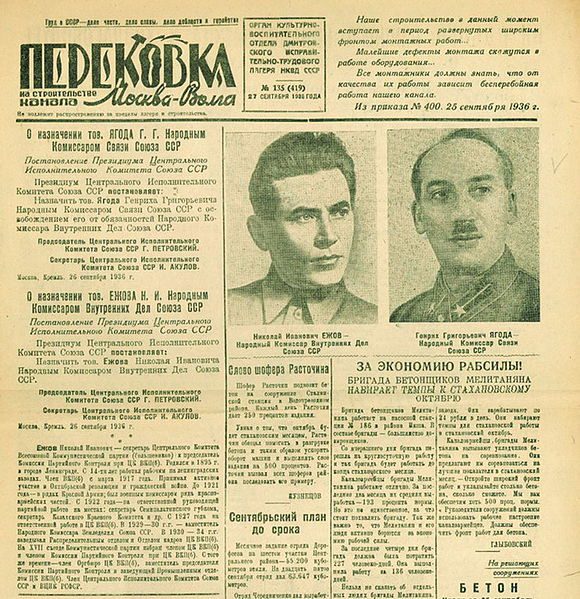

Aside from Iván and Ramón, Padura shows us one of the twentieth centuries’ most violent displays of state control of knowledge: Stalin’s show trials. During the Soviet Terror of the 1930s, it was not enough to confess to being a Trotskyist-Bukharinite Japanese-German fascist spy. Defendants were made to perform self-criticism, ultimately regurgitating newly-fashioned realities of their nonexistent transgressions in public court. The Soviet government had the power to extract these false confessions, even from its own executioners, and then to force them to speak them into reality. Understanding the power of this performance is why Ramón’s handlers in Moscow bring him to not just any show trial, but the trial of Genrikh Yagoda, the former head of the NKVD (later the KGB). The lesson here for Ramón was precisely about truth, which in his case means one thing: obedience. As his handler puts it: “No one resists. Not even Yagoda. Neither will Yezhov when his turn comes.” Spoiler: Nikolai Yezhov, Yagoda’s successor, doesn’t even last another two years.

Soviet newspaper “Perekovka” (“Reforging”), front page announcing the replacement of Genrikh Yagoda by Nikolai Yezhov, 1936 (via Wikimedia Commons).

Trotsky, on the other hand, is more characterized by disobedience than anything else, and his own struggle helps to put the others in perspective. Our narrator tells us: “The struggle on which he had to focus from that moment on would be one against men, against a faction, never against the Idea.” Trotsky’s struggle was against Stalin and anyone who bought into Stalin’s interpretation of the “Idea.” The Idea, he explains, is “the truth of the revolution,” and he wishes to “throw himself into the void and proclaim the need for a new party capable of recovering” it. His crusade had always been to establish himself as the bearer of that truth, for the sake of which he committed bloody “excesses” that he would later claim to regret. Whereas Ramón and Iván are coerced to obediently accept and promote the Soviet government’s Truth, Trotsky seeks to convince others that he is the one with the real Truth, so everyone should obey him. The guilt over his “excesses,” and the fear that his command over Truth might transform him into “a pseudo-communist czar” like Stalin, was ultimately insufficient to dissuade him altogether.

Tragically for the book’s heroes, it turns out they were struggling for nothing. In fighting “men” instead of the “Idea,” Trotsky forgot, as Dany reminds us, to “think about people.” They are the ones, after all, creating the ideas. The Soviet government certainly recognized as much, since in ordering Ramón to destroy Trotsky, they sought to destroy a particular set of ideas that threatened their own. Of course, we’ve heard these critiques of Soviet-style communism before. But at the heart of Padura’s book is something much farther reaching: it is the impossibility of utopia, communist or otherwise, and moreover, the destruction of knowledge that utopian projects inherently entail. For Padura, the construction of any utopia is a violent struggle over control of the “truth,” a struggle that leaves no room for the people for whom the utopia is supposedly built. Trotsky even acknowledges as much when he notes that the first executions from the show trials spelled the “death rattle of utopia;” Iván and Ramón were its “gullible” victims. It is no mistake, as Dany concludes, that the only utopia available to them is the one beyond the grave.

Leonardo Padura, The Man Who Loved Dogs (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2014).

![]()

Also by Rebecca Johnston on Not Even Past:

Policing Art in Early Soviet Russia.

You may also like:

Capitalism After Socialism in Cuba, by Jonathan C. Brown.

The Old Man and the New Man in Revolutionary Cuba, by Frank A. Guridy.

![]()