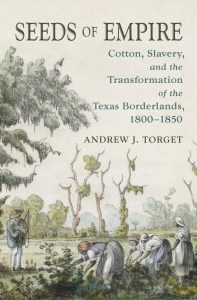

Andrew Torget’s Seeds of Empire places the early history of nineteenth-century Texas squarely within the political economy of slavery, cotton, and geopolitics. Torget shows that Spanish Texas had become an utterly dysfunctional polity. A royalist bloody response to the creation of autonomous creole juntas almost led to the annihilation of the Tejano population. Tejas found itself unable to pay the Comanche tribute precisely at the time that the Mississippi River cotton boom required large imports of horses. Comanches raided the already weakened Tejanos.

Andrew Torget’s Seeds of Empire places the early history of nineteenth-century Texas squarely within the political economy of slavery, cotton, and geopolitics. Torget shows that Spanish Texas had become an utterly dysfunctional polity. A royalist bloody response to the creation of autonomous creole juntas almost led to the annihilation of the Tejano population. Tejas found itself unable to pay the Comanche tribute precisely at the time that the Mississippi River cotton boom required large imports of horses. Comanches raided the already weakened Tejanos.

Tejanos found in Anglo entrepreneurs like the Austin family a viable escape from a decades long crisis. The Austins brought Anglo, land-hungry colonists across the Sabine River into Eastern Texas in the early 1820s by offering legalized slavery. There were many Anglo land speculators around but none delivered what the Austin did, namely, cunning diplomatic work to keep republican, antislavery, federalist Mexicans and pro-slavery Anglo colonists moderately satisfied.

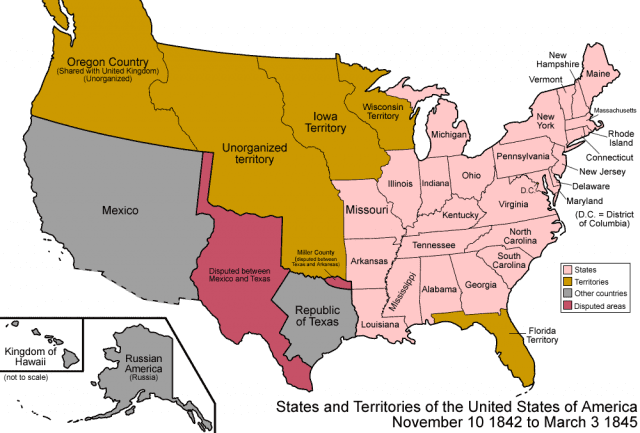

Torget describes the spatial partition of Texas that ensued. In the west, there were thin communities of Tejanos working as pro-slavery lobbyists in Coahuila and as importers of Anglo goods to satisfy the demands of La Bahia, Goliath, and San Antonio. In the east, there were swelling communities of Anglo settlers setting up plantations along the banks of the Colorado, Brazos, and Trinity, while churning out bales of cotton for New Orleans markets. Torget never explains why Tejanos did not themselves become cotton planters. There were Tejanos in Nacogdoches who monopolized the Comanche trade of horses and there were many well-off Tejano war-of-independence-refugees in New Orleans. Both could have used their political and commercial advantages to push Anglos out of the business of producing cotton with slaves, for Tejanos were not squeamish about slavery. For centuries Tejanos incorporated Apache criados (servants) into their household and drove thousands of Chichimeca captives into the silver mines of Parral and Zacatecas and into the cattle ranches of Nuevo Leon. Tejanos did not hesitate to feed the Caribbean royal galleys and fortifications with slaves. Be that as it may, a deep ethnic chasm did open between east and west Texas. This spatial and political balance, however, unraveled the moment the elites of Mexico City decided that they were losing control over the northern frontiers. Mexican conservatives, therefore, abolished slavery, terminated land contracts, and sent the army to remove the Anglo settlers.

Torget demonstrates that it was a small, fleeting tactical decision by Santa Ana that sealed the faith of Texas in 1835, as thousands of Anglo colonists were in fully disorganized retreat to the safety of the Louisiana border. At the Brazos, however, Santa Ana split his army into two fronts to block the retreating forces of Sam Houston from crossing the Sabine. Houston stopped fleeing and turned around to engage Santa Ana’s forces. This was the moment Texas became an independent republic nobody wanted, including the Anglo colonists. Tejanos were the ones who lost the most as useless lobbyists. They had to give up lands and the rights of citizenship.

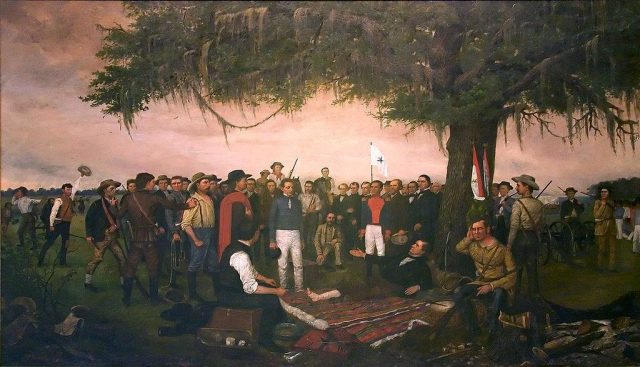

William Henry Huddle’s painting, Surrender of Santa Anna, shows the Mexican general surrendering to a wounded Sam Houston after the battle of San Jacinto in 1836 (via Wikimedia Commons).

Torget shows that the Lone Star State remained an utterly nonviable state for a full decade (1835-45), trapped in the logic of much larger geopolitical balances that pitted Great Britain, the USA, and Mexico against one another. Five of these ten years, however, witnessed an unprecedented cotton boom in the Mississippi Cotton Kingdom. It brought tens of thousands of additional colonists and black slaves to the riverine banks of Eastern Texas and new merchant warehouses to the Galveston Bay. But the boom did not bring any changes in riverine infrastructure, a sovereign port, or a national merchant marine. There was no functioning state, no mechanism to collect taxes, and no diplomatic working corps.

Britain sought to convince Texans to gain diplomatic recognition by becoming a free-labor cotton republic. Texans responded by creating a constitution that banned any black person who had been manumitted from residing within the new nation. The United States had no interest in annexing Texas because it would upset the balance between northern and southern states.

The plight of Texas worsened as the cotton boom went bust in late 1839. The only thing that Texas did well was to organize militias to bleed the raiding Comanche. Torget explains how the geopolitical logjam was broken the moment France finally recognized Texas in 1844. To secure one of the most important sources of cotton for its economy, Britain had no choice but to also recognize Texas. It was only then that Anglo Texans got what they had always wanted: annexation into the United States. Incorporation delivered a functioning government, protection against international anti-slavery forces and Mexican invasions, and a windfall for land speculators as land prices rose to the equivalent of those in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana. Cotton, Slavery, and Empire are categories that explain rather well the origins of Texas as a white supremacist state, utterly dependent on the federal government from its very inception.

Andrew J. Torget. Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850. Charlotte: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

![]()

More by Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra on Not Even Past:

Our America: A Hispanic History of the United States, by Felipe Fernández-Armesto (2014).

Re-Reading John Winthrop’s “City upon the Hill.”

Magical Realism on Drugs: Colombian History in Netflix’s Narcos.

Prof. Cañizares-Esguerra discusses his own book, Puritan Conquistadors.

![]()